The tragedy of the European Jews and people recognised as such began with Adolf Hitler’s accession to power. The National Socialists, whom Germans elected in a democratic election as early as in April 1933, passed the first anti-Jewish laws three months into their term. More were introduced in the following years, and a series of pogroms conducted in November 1938 became known as Kristallnacht (Crystal Night).

Late in the 1930s, the Germans mostly wanted to “get rid of Jews” by forcing them to emigrate. The outbreak of the war, starting with the invasion of Poland, greatly aggravated the fate of Jews in other countries as well. In occupied Poland, murders of Poles and Jews were rife, and synagogues and houses of prayer were destroyed. After hostilities ceased, a number of legal prohibitions were imposed on people recognised as Jews. They were placed on a register, disqualified from entering certain districts in the cities, and forced to give up the businesses they owned. Soon the separation of Jews from “Aryans” began. Plans were made to set up a special Jewish “reservation” in the area around Lublin. Eventually the idea was rejected and ghettos began to sprout, with the first being established in Piotrków Trybunalski early in October 1939. By mid-1941 there were around 400 of them. The next stage of the Shoah commenced after the outbreak of the German–Soviet war in June 1941. Murdering Jews in occupied territory became an everyday event in which the German Einsatzgruppen specialised. To all intents and purposes, by that time the decision that all Jews were to be murdered in the future had already been taken. In October 1941, Hans Frank issued regulations that allowed the execution of any Jews leaving a ghetto without a permit and all people assisting them. A detailed plan for the elimination of the Jews was worked out at a council meeting in Berlin-Wannsee held early in 1942. In the wake of its implementation and of earlier crimes, nearly 6 million Jews, of whom every other was a Polish citizen, were murdered, mostly in the death camps.

“We are trying to cease to exist…”

The fate of Cracow Jews did not differ much from the situation of their fellow Jews in other major cities of the General Government. There were nearly 55,000 Jewish residents in Cracow before the war, nearly a quarter of the entire population: a number that grew to nearly 70,000 in November 1939 in the wake of wartime movements of population, including forced resettlement from the lands of Western Poland incorporated directly into the German Reich.

Following the invasion, Jewish shops had immediately to be marked with the star of David, and from 1 December 1939 that sign had to be worn by all Jews of and over 12 years old. Soon Jewish schools were disbanded, employment became obligatory, the use of public transport banned, and a curfew introduced at 9pm. As Cracow was chosen for the capital of the General Government (GG) and the city was intended to become German to the highest possible degree; its “cleansing” began with the “resettlement” of Jews. In April 1940, the German authorities ruled that only 10,000 Jews can stay temporarily in Cracow. Actually, around 60% of the Jewish population had been removed by early 1941, most of their number finding new residences in the vicinity. The Cracow rabbis asked, among others, the Archbishop of Cracow, Reverend Adam Stefan Sapieha, for help in the endeavour of discouraging the Germans from carrying out that campaign. Not only was his plea to the authorities of the General Government regarding the case ignored, but the instigators of the idea were arrested and transported to KL Auschwitz, from where they never returned. The Germans also endeavoured to make Jews an abomination in the eyes of Poles and released anti-Semitic propaganda. The streets were arrayed with posters with insulting slogans, reading for example “Jews – the ferment of moral decay” and “No admittance to dogs and Jews”.

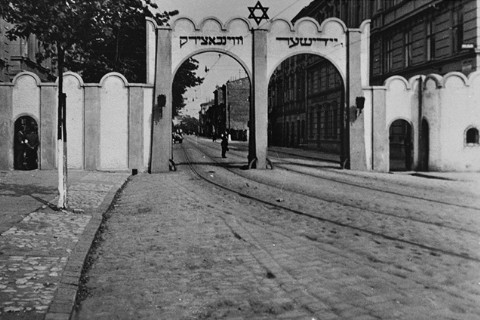

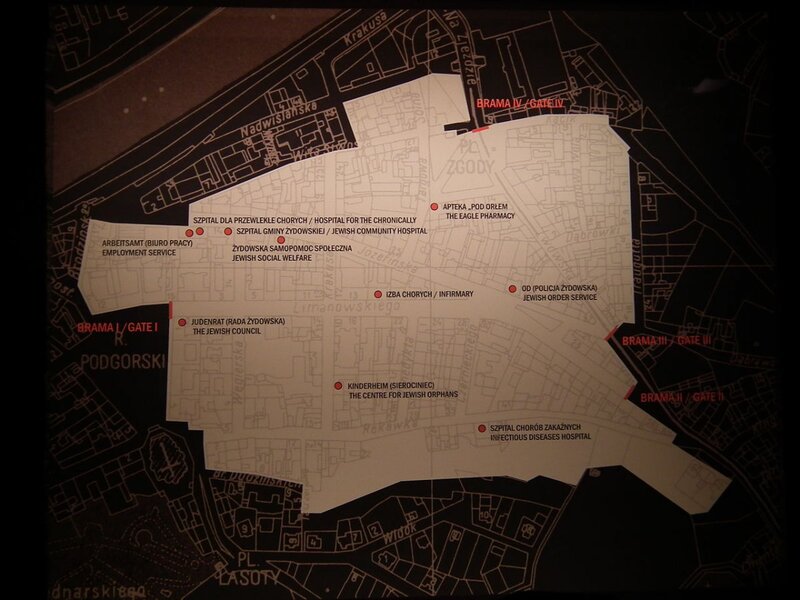

Soon, the German authorities decided to set up a ghetto in Cracow. As most Jews had already been forced to leave the city, it was relatively small: 320 houses with nearly 3200 rooms (at its peak, the largest ghetto, in Warsaw, was inhabited by 450,000 people) and it was situated in the district of Podgórze, on the other side of the Vistula River, to move the Jews as far away as possible from the districts inhabited by Germans. An appropriate bylaw was published on 3 March 1941. In a matter of two weeks, 12,000 people were moved to the ghetto, a number that soon grew to 17,000 as several thousand more were later forced into the ghetto. The conditions in the ghetto were abhorrent. This is how Roma Ligocka reminisces about the place: “The ghetto has four big gates. We are not allowed to go through them. (…) Everything is forbidden, and yet we can never be sure whether we are not doing something that is even more forbidden, and from which direction the bullet will come flying. We are trying to meld into the stones, the walls. We are trying to cease to exist.”

When the Germans decided upon the last, most tragic stage of the Shoah, they began to vacate the Cracow ghetto. Around 14,000 people altogether were deported to the death camp in Bełżec in June and October 1942, with more than a thousand murdered in the process. In December 1942 the area of the ghetto was reduced, and the expansion of the Plaszow camp commenced.

The Shoah…

Many Cracow Jews, and especially Poles whom Germans considered Jews, did not want to move to the ghetto. The fact that they were largely assimilated made it easier for many of them. In their case, just “the proper good looks” and false documents could be enough to survive. The hardest time for the Jews hiding in Cracow came in late 1942 and early 1943, which was when the Germans ordered an intensification of searches for those staying outside the ghetto. The danger was especially high because of the blackmailers (shmaltsovniks) and informers. It is impossible to ascertain their number due to the lack of documents, but nonetheless they were a grave danger, not only from those in hiding, but also from those who assisted them. Research, notably that published by Krystyna Samsonowska, demonstrates that there was a relatively high level of assistance from Polish people in Cracow and it came not only from individuals, but also from numerous political circles, especially those linked to the Polish Socialist Party. Moreover, many Catholic priests would not refuse to issue false birth certificates and monastic orders not only admitted Jewish children but also Jewish adults within their walls: for example the Felician Sisters provided shelter to, among others Maria Kiepura, the mother of the famous singer. A chapter of Żegota, the Polish Council to Aid Jews, initiated its operation in Cracow in the spring of 1943. It not only helped in obtaining false documents and finding shelter in Cracow and in the province, but it also managed relocation to Hungary. By the end of 1943, permanent assistance was extended to over 500 Jews.

The liquidation of the Cracow ghetto took place on 13 and 14 March 1943. Two thousand Jews were murdered on the spot, mostly in plac Zgody square, renamed later into the Square of the Heroes of the Ghetto. Photographs documenting numerous corpses in the streets of Podgórze have survived. “Blood flows in rivulets over the cobbles. Shattered parcels, suitcases, bags, and books bound in velvet lie everywhere around. The yelling and the screaming combine into a single awe-inspiring sound. I am looking into the dead eyes of the people lying next to me. They are glass-like. Open wide. Extinguished.” Roma Ligocka, the girl in the red coat, remembered. The remaining three thousand were deported to KL Auschwitz or forced to the nearby Plaszow camp.

Only those Jews who could be used as slave labour found their way to the Plaszow camp, transformed into a concentration camp in January 1944. The ghastly conditions of life in the camp and the exhausting work resulted in a very high mortality. The head of the camp was Amon Leopold Goeth, a madman who not only supervised the extermination of the inmates, but would at times choose to execute them in person, often without the slightest pretext. With the approaching line of the front, the camp was practically liquidated in the summer of 1944, and many inmates transported to KL Auschwitz, where they were gassed. Only around a thousand people survived from the Plaszow camp as, thanks to Oskar Schindler, they were transported to camps in which they managed to survive to the end of the war.

Mateusz Szpytma Ph.D.,

An excerpt from Od Września do Norymbergi (literally: “from September to Nuremberg”),

a book ed. by Filip Musiał, Jarosław Szarek, Cracow 2012