Two months earlier, events had taken place that occupied an important place in the Polish historical calendar: in December 1970, shipyard workers made a blood sacrifice during the revolt on the Coast, triggered by rising prices of meat and other foodstuffs, but it was the women of Łódź who led to the cancellation of a price increase. But who remembers this today?1 In liberated Poland the image of the February protest was trivialized, reduced to a meeting with a government delegation during which one or several textile workers were supposed to show their bare bottoms to the communist politicians. The facts are that until Solidarity was formed, the Łódź strikes were the only protests won by the workers.

Before it blew up

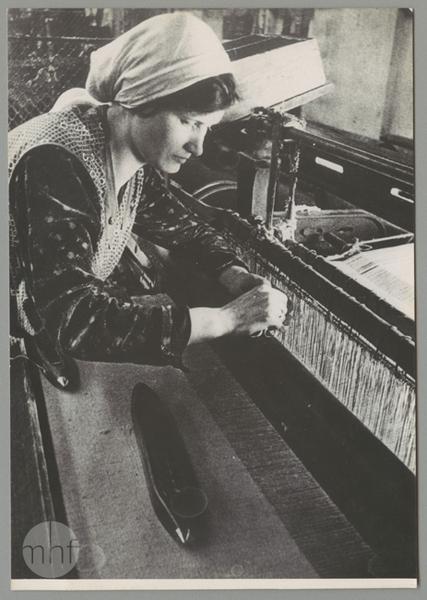

In 1970 there were 755,000 inhabitants in Łódź, including 405,000 women. There were 413,000 people working in the state economy, 204,000 of whom were women. The economic activation rate of women in Łódź was 87% – the highest in Poland. The face of the textile city was determined by light industry (over 130 thousand workers, including 90 thousand women), concentrated in 61 cotton, woollen, knitting, hosiery and clothing enterprises, 11 unions, 2 foreign trade centres, 3 design offices and 2 scientific research institutes. The average wage of a textile worker was about 20 percent lower than the national average and in 1969 amounted to PLN 1994.

The strikes in Gdańsk, Gdynia, Elbląg, and Szczecin in December 1970 did not provoke solidarity protests in Łódź, even though considerable police and army forces were mobilized in the city to pacify any possible manifestations hostile to the local authorities and the Polish United Workers' Party. Two branches of the “Majed” Silk Machine Factory in Łódź stopped working for an hour on December 18, and a day later one hundred workers of the Mechanical Department of the Widzew Textile Machine Factory commemorated the victims of the massacre on the Coast with a moment of silence. From the beginning of 1971, despite external signs of calm, there was a growing dissatisfaction with the economic situation in Poland simmering among the employees of the Łódź plants. By mid-January, it began to escalate into small-scale protests. About 70 workers of the Meat Plant stopped work for several hours on January 15, and five days later 65 workers of the Central Clothing Factory in Łódź followed suit.

Edward Gierek, the new First Secretary of the PZPR (Polish United Workers' Party) Central Committee, went to quell the workers’ strike at the Adolf Warski Shipyard in Szczecin on January 24, 1971, and met with shipyard workers in Gdańsk the next day, where, contrary to the later propaganda manipulation of the mass media, and instead of declarations of support (there was no "we shall help" response) there was just applause from the floor. Gierek's team condemned the use of force during the suppression of strikes and announced a change in the economic policy, but at the same time did not cancel the pay rises. The authorities felt confident and it was in this situation that the Łódź textile workers entered the scene. The rebellion broke out this time in a city with the highest infant mortality rate in the country, where women worked three piecework shifts in conditions that created a natural setting for Andrzej Wajda'sPromised Land2, requiring virtually no decorative work.

Start

Before noon on February 10, 1971, the protest was launched by the Łódź Factory of Footwear and Rubber Products "Stomil", which employed 4,200 workers. The most spectacular strike broke out on the same day at the waste spinning mill of the Julian Marchlewski Cotton Industry Plant, which employed about 9,000 people. Its direct cause was the information about the reduction of employees' salaries by PLN 200-300 in January, which, combined with the December increase in food prices, meant a significant worsening of their already difficult material situation. In addition to the demand of a 20 per cent pay rise for the textile workers, there were demands for a transparent method of determining wages, fair calculation of holiday pay and a fair distribution of export bonuses.

The breakthrough events for the Łódź strikes took place on February 12 and 13. The protest was joined by other departments of the “Marchlewski” ZPB (Cotton Plant) and six other cotton mills: “Defenders of Peace” (2,500 workers did not start work), “May 1st” (about 1,100 people), “People's Army” (about 1,000), “General Walter” (130), “Stanisław Kunicki” (137), and “HankaSawicka” (550). As early asFebruary 12, over 12,000 people were on strike in Łódź, 80 per cent of whom were women, and such a significant revolt could not be pacified by promises or small concessions from the management of the plants. In this situation, the intervention of the central authorities proved necessary. In the evening of February 11, the First Secretary of the ŁódźPZPR Committee, JozefSpychalski, arrived at the “Marchlewski” ZPB (Cotton Plant) meeting only with party activists, and not with staff. Talks held a day later with the Warsaw delegation, consisting of Deputy Prime Minister Jan Mitręga, Minister of Light Industry Tadeusz Kunicki and Chairman of the Central Council of Trade Unions WładysławKruczek, failed. It turned out that the representatives of the authorities had nothing to offer the strikers and their efforts were limited to informing the textile workers about the lack of possibilities to increase salaries and in persuading them to join the work. It was during the aforementioned discussion with Deputy Prime Minister Mitręga that one of the embittered textile workers demonstrated her bare buttocks to the delegation arriving from Warsaw. The failure of the talks only contributed to the extension of the strikes3.

Escalation

The first days of the protest have clearly shown the crucial importance of the "Marchlewski" ZPB (Cotton Plant). On February 13 the crew of this factory broke off talks with the factory administration and demanded that Gierek come or that wages be raised by PLN 250. The lack of response to these demands led to the beginning of the occupation of the plant. The next day, Sunday, the occupational strike continued only in the “Marchlewski” and “Defenders of Peace” cotton plants. Crews at the remaining factories returned home, announcing that the protest would continue on Monday.

At a meeting of the Political Office of the PZPR Central Committee held on February 13, a decision was made to solve the problem of the strikes by political and economic means. The threat of a violent end to a large protest with a majority of women, the outbreak of a general strike, as well as the experience of December 1970, prompted Gierek's team to send a delegation to the strikers, including Prime Minister Piotr Jaroszewicz and members of the Political Office of the Central Committee Jan Szydlak and Józef Tejchma.

On February 14, the representatives of party and state authorities began their stay in Łódź with a meeting in the Grand Theatre with Łódź activists of PZPR, trade unions and youth organizations. However, the Warsaw delegation learned the true picture of the situation in Łódź only after they had arrived at the two largest of the striking factories: the “Marchlewski” and “Defenders of Peace” ZPB (Cotton Plants). During the meeting with the employees of the first of these plants, Prime Minister Jaroszewicz found it difficult to speak, as he was being shouted down and the women kept on bursting into tears. When he managed to break through, he tried to convince people to break the strike, he appealed for trust in the new management, he guaranteed, on behalf of the government, that the situation of the textile workers would improve, but at the same time he emphasized that it was impossible to fulfill the demands for wage increases. These words were met with the strikers’ discontent. They repeated their demands for a pay rise and for no consequences to be drawn against the participants in the strike. They presented problems related to poor organization of work and medical care, lack of machine parts and quality raw materials, overstaffing of management, inappropriate attitude of administration towards textile workers and wage disparities between workers and factory bureaucracy. The meeting ended in a massive scuffle. Szydlak's speech was interrupted by violent shouts, and when Jaroszewicz again tried to persuade the gathered to break the strike, one of the textile workers snatched the microphone from him.

In this situation, the government delegation left the conference room in the “Marchlewski” plant in great confusion and haste, and on the night of February 14-15 went to further negotiations with the workers of the automatic weaving and finishing plant of the “Defenders of Peace” ZPB. There, too, the most important demands of the first meeting were repeated, and the strikers again gave vent to their bitterness. The Prime Minister and the prominent representatives of PZPR, who accompanied him, adopted a different strategy this time. Seeing the determination of the gathered textile workers, they put all the blame for the bad situation of the light industry on the team of WładysławGomułka. They assured those assembled of the ignorance of Gierek and his colleagues about the condition of the industry and promised an immediate improvement in working and living conditions.

However, the strikers did not succumb to this political propaganda, neither did they believe the promises made them. As a result, after the meetings with the Prime Minister the crews of Łódź factories did not break the strike. On the contrary, it was on February 15 when it reached its climax. The last three plants of the cotton industry – “Feliks Dzierżyński”, “Szymon Harnam”, “Stanisław Dubois”, and seventeen plants from other industries – joined in. The protest has already covered 32 factories, including all in the cotton and wool industry, and a total of 55,000 workers have not joined the work. The strikes in Łódźthus went beyond the framework of a local rebellion of a few isolated factories4.

Retreat of authorities and phasing out of strikes

Concerned by the escalation of discontent, the communist authorities decided to make concessions. During his stay in Łódź, Prime Minister Jaroszewicz realized, as he recalled years later, that there were two possible solutions to the conflict. Either the wages of the textile workers had to be raised or the price increases of December 1970 had to be quickly withdrawn. It was easier to choose the second option because a wage increase for one occupational group could trigger a wave of wage claims from other groups. Still on February 15, in the evening, an announcement was broadcast that the Council of Ministers decided to lower food prices from March 1 to the level from before December 1970. The striking workers were also guaranteed security. In this situation, the delegations from other plants that arrived at the central place of protest, i.e. the “Marchlewski” ZPB, considered that the goal of the strike had been achieved. The revolt of the Łódź textile workers came to an end and on February 16 most of the crews went to work. The last factories, “Defenders of Peace” and “Feliks Dzierżyński”, did it the next morning. However, the situation in the Łódź agglomeration after the textile industry strike ended did not immediately return to normal. From February 18 to 25 the strikes continued at the Łódź Vodka Factory, the Łódź Cigarette Factory, the Pabianice Paper Factory and the Pabianice Road Machinery Factory. Short-lived work stoppages on account of wages were still observed in March 1971 in several plants5, but much larger strikes broke out outside Łódź at that time: on March 4-5 in Zelów, on March 8 in Bełchatów, and on March 16-17 in Ozorków.

Reactions of the Security Service

The significance of the protest and the uncertainty of the authorities about the further development of the situation can be proved by the amount of forces and means deployed by the Security Service in Łódź to counteract the textile workers' strike. From February 10 to 17, officers from Divisions II, III, and IV of the Municipal Police Headquarters held 343 meetings with undercover collaborators (UCs) and 961 with operational contacts and service contacts (OCs and SCs), receiving a total of 983 pieces of information from them. In the same period the Security Service recruited 6 new UCs and acquired 113 OCs and many SCs. Apart from personal sources of information, the Security service in Łódź made intensive use of the means of operational techniques in its activities. In fact, at that time it had 80 points of telephone tapping and 15 points of room tapping. Using them, the "T" the Łódź Municipal Police Headquarters intercepted and forwarded to the operational units concerned 134 messages from telephone taps, including 53 relating to the situation in striking enterprises, and 35 messages from room taps, of which 12 were directly related to the strikes. During the protest in Łódź the "W" Department was also exceptionally active; its employees controlled 44,146 documents, including 374 pieces of foreign correspondence. As a result of this control, they seized 35 original documents allegedly containing, among other things, 15 false information about the situation in Łódź and 8 poetic pasquiles. In preventing the protest from spreading, officers of the “B" Department were also involved, and by observing people and objects they monitored the situation in the main points of the city and around the plants6.

What did Richard Nixon find out on February 17?

In early 2017, the US Central Intelligence Agency released 13 million pages of secret documents from the Cold War. It featured the presidential bulletin, which arrives on the desk of the U.S. leader every morning and includes a summary of major world events. The recipient of the bulletin dated February 17, 1971 was Richard Nixon. The uniqueness of this documentary lies in the fact that apart from reports from Asia – China, India, Pakistan, Laos and Vietnam, where the war was going on at that time – there was also information from Łódź about the finished occupational strike of light industry workers. The communist authorities decided to cancel food price rises to prevent a third wave of strikes. According to the CIA, Prime Minister Jaroszewicz announced that price cuts could not entail further concessions, tying the government's ability to lower prices to obtaining loans from the USSR. "It seems – the message concluded – that in this way Jaroszewicz is trying to remind the workers that the Soviets always recover their debts."7

The success of the protest

The February 1971 strike in Łódź had an economic dimension, it was not a political rebellion. It should not be forgotten, however, that in the communist state every gesture of opposition and independent thinking was treated as a political act, which the authorities fought ruthlessly. The protest of the Łódź textile workers – as Krzysztof Lesiakowski, a researcher on the Łódź strikes, rightly noticed – was not planned, it was a spontaneous grassroots undertaking. No strike committee was formed to negotiate, no list of demands and postulates was created, there was no proper communication between striking factories. However, the crews of individual plants maintained contact with the “Marchlewski” factory, recognizing its leading role in the Łódź protest – the equivalent of the Gdańsk Shipyard on the coast in December 1970. The strike did not create clear leaders, but only factory leaders, among whom we can point to mechanic Wojciech Lityński and weaver CzesławaAugustyniak. On the other hand, it is clear from the Secret Service documents that during the protest a group of workers' activists emerged, who stopped machines, urged hesitant workers to stop work, and appeared at meetings with local and central authorities. The strikes of the Łódź textile workers were the third wave of protests since December 1970, but they were successful, leading to the withdrawal of price increases8.

The text appeared in the Institute of National Remembrance’s Bulletin No. 6 (151), June 2018

Author: Paweł Perzyna

Footnotes

- Amnesia also accompanied the decline of the textile industry as part of the economic transformation after 1989. The fact that women would not go to Warsaw with shuttlecocks and spindles instead of miners' pickaxes and plowshares to storm government buildings and fight for privileges for women textile workers was cynically taken advantage of.

- K. Lesiakowski, Strajk robotników łódzkich w lutym 1971 roku, „Pamięć i Sprawiedliwość” 2002, no 1, pp. 133–136; idem, Służba Bezpieczeństwa wobec środowisk robotniczych Łodzi w grudniu 1970 i lutym 1971, [in:] Dla władzy. Obok władzy. Przeciw władzy. Postawy robotników wielkich ośrodków przemysłowych w PRL, ed. by J. Neja, Warsaw 2005, pp. 88-97; idem, Strajki robotnicze w Łodzi 1945-1976, Łódź 2008, pp. 261-266; Strajki łódzkie w lutym 1971. Geneza, przebieg i reakcje władz, selection, introduction and analysis by E. Mianowska, K. Tylski, Warsaw 2008, pp. 19-21; M. Matys, Kto pokazał tyłek Jaroszewiczowi?, [in:] P. Lipiński, M. Matys, Absurdy PRL-u, Warsaw 2014, pp. 18-19.

- K. Lesiakowski, Strajk robotników łódzkich..., 136-138; idem, Strajki robotnicze..., pp. 284-288, 296; Strajki łódzkie..., pp. 12-13. For years there was a sensational rumor that the scene in question took place during a meeting with Piotr Jaroszewicz. See M. Matys, Ktopokazałtyłek…, pp. 21–22.

- K. Lesiakowski, Strajk robotników łódzkich…, pp. 138–140; idem, Strajki robotnicze…, pp. 297–305; Strajki łódzkie…, pp. 13–15; B. Pawlak, 10 lutego 1971 r. – „zapomniany” strajk łódzkich włókniarek, http://dzieje.pl/aktualnosci/rocznica-wybuchu-zapomnianego-strajku-lodzkich-wlokniarek [accessed: April 25, 2018]. The declaration that the strikes would be resolved peacefully was contradicted by bringing army and militia units to Łódź. Key facilities in the city were manned by soldiers of the 8th Regiment of the Internal Defense Forces, and militia reinforcements were brought from Piotrków Trybunalski, Kutno, and Piaseczno. K. Lesiakowski, SłużbaBezpieczeństwa..., p. 99.

- The authorities, both during and after work stoppages, sought to identify the most active participants in the strike. By March 5 the personal data of 26 people from the "Marchlewski" ZPB and 11 from the “Defenders of the Peace” ZPB were determined. Gradually, pressure began to be put on them to vacate their jobs. K. Lesiakowski, Strajkrobotnikówłódzkich…, pp. 141–142; Strajkiłódzkie…, pp. 15–16.

- K. Lesiakowski, Służba Bezpieczeństwa..., pp. 104-105; idem, Strajki robotnicze..., pp. 321-322. See also the analysis of communications with personal informants during strikes (doc. 42), [in:] Strajkiłódzkie…, pp. 132–138.

- The President's Daily Brief (PDB) 17 February 1971, https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/document/0005992485 [accessed: 25 April, 2018]; I. Rakowski-Kłos, CIA Reports. Co Richard Nixon wiedział o łódzkich włókniarkach, http://lodz.wyborcza.pl/lodz/7,44788,21324478,raporty-cia-co-richard-nixon-wiedzial-o-lodzkich-wlokniarkach.html [access: April 25, 2018].

- K. Lesiakowski, Strajki robotnicze..., p. 294; Strajki łódzkie..., pp. 15-16.

Excerpts

In liberated Poland the image of the February protest was trivialized, reduced to a meeting with a government delegation during which one or several textile workers were supposed to moon the communist politicians.

Two branches of the “Majed” Silk Machine Factory in Łódź stopped working for an hour on December 18, and a day later one hundred workers of the Mechanical Department of the Widzew Textile Machine Factory commemorated the victims of the massacre on the Coast with a moment of silence.