The deceased are normally tended to by their families, who make sure that they receive proper treatment, are buried in line with the rites of their religion or wishes, and laid into graves that commemorate them as required by custom, law, or – again – their wish. Safeguarding the dignity of the dead is the responsibility of the relatives, and that’s a given. However, large-scale calamities, such as armed conflicts resulting in mass loss of life, chaos and destruction, often make the obligation a tall order to fill, or and impossible one.

That’s why international law makes states responsible. Article 15 of the 1st Geneva Convention of 1949 explicitly says that "At all times, and particularly after an engagement, Parties to the conflict shall . . . search for the dead and prevent their being despoiled." It’s not always possible – nothing remained of the people who perished in German concentration or death camps and were cremated en masse, especially when their ashes got scattered in rivers (like in Auschwitz) or lakes (in Ravensbrück) – but whenever it is, the same GC I in Article 17 requires that,

Parties to the conflict shall ensure that burial or cremation of the dead, carried out individually as far as circumstances permit, is preceded by a careful examination, if possible by a medical examination, of the bodies, with a view to confirming death, establishing identity and enabling a report to be made.

That does not exhaust a state’s obligations, though:

They shall further ensure that the dead are honourably interred, if possible according to the rites of the religion to which they belonged, that their graves are respected, grouped if possible according to the nationality of the deceased, properly maintained and marked so that they may always be found.

In fact, all four Geneva Conventions outline the institutional treatment of the dead, the obligation detailed by bills, statutes, as well as bilateral and multilateral agreements and treaties. The IPN carries it out, but does more than that because in addition to the responsibility stipulated by international law, it considers itself a stakeholder and acts accordingly with three objectives in mind: identify the victims to give them proper burial, let the relatives know, name, and if possible, prosecute the perpetrators. That’s where Krzysztof Szwagrzyk and his team come into the picture.

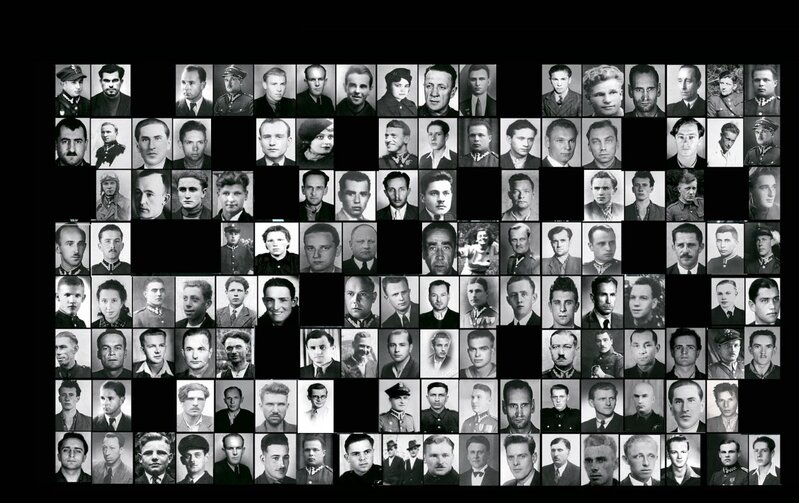

They have been involved in locating burial sites and identifying victims since 2003; in 2016 the team was reorganized into one of the Institute’s main divisions, and then expanded severalfold. So far, they’ve found over 1,500 bodies and matched names to a tenth of them. That means 150 people brought back from oblivion and 150 families released from unawareness. More importantly, that means a whole generation made aware of the nation’s past sacrifices – because their mission is translating each body they unearth into a messenger speaking to thousands.

Bronisław Chajęcki thus speaks about his 1953 hanging in the Mokotów Prison in Warsaw; Zofia Ginter reveals the details of the mass execution by Gestapo officers in Białystok that killed her; Feliks Gołębowski recounts his death at the hands of the Ukrainian nationalists in south-eastern Poland; Danuta Siedzikówna tells the story of her 1946 shooting in Gdańsk; Stanisław Łajczak and Jan Ficek muse over their entrapment and treacherous murder by communist security services in Stary Grodków, along with the rest of their unit.

Many more people are waiting for an opportunity to tell their stories: Sister Aniceta Skibowski is just about to relate her 1945 murder by the Red Army troopers, Cpt. Witold Pilecki has yet to describe what he saw in the eyes of his communist executioner Piotr Śmietański, soldiers fallen in local and nationwide wars and uprisings, from 1917 to 1945, from Westerplatte to Stanisławów, still haven’t had the chance to speak up. The IPN’s Office of Search and Identification staff are working to take them out of the ground and make sure they will.

-

Office of Search and Identification - exhumation work -

Office of Search and Identification - exhumation work -

Office of Search and Identification - exhumation work -

Office of Search and Identification - exhumation work -

Office of Search and Identification - exhumation work -

Office of Search and Identification - exhumation work -

Office of Search and Identification - exhumation work -

Office of Search and Identification - exhumation work

Despite the pandemic, in the past year alone the Office experts examined 53 former camps and prisons, battle sites, cemeteries, and unmarked plots in Poland and abroad, locating the remains of nearly 150 victims of German and communist crimes. They found, for instance, secret burial sites on the grounds of "Toledo", a former security service jail in Warsaw, continued their search for "Hubal", the legendary partisan who fought the Wehrmacht in September 1939 and the first months of the occupation, or unearthed a boy killed by the Germans in 1943.

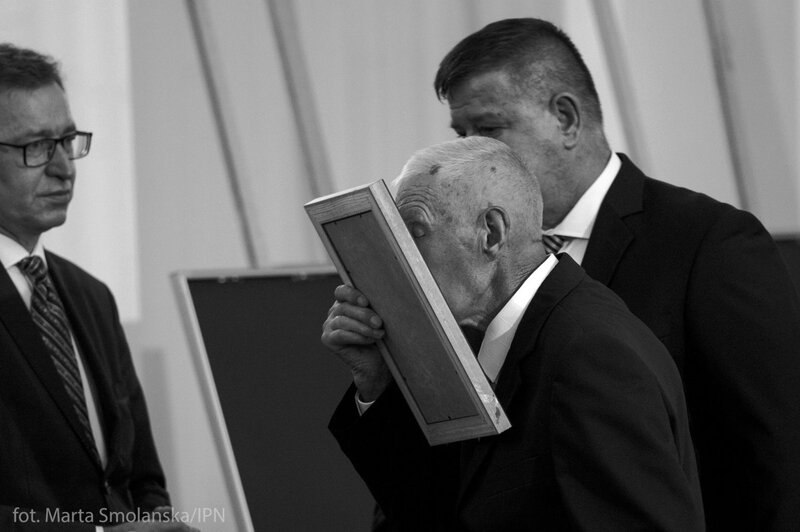

The Office staff – historians, archivists, archeologists, anthropologists and geneticists – invariably call great job satisfaction the most important item in the employee benefit package. It’s made up of the thrill of uncovering a part of history, but its more important element is that unique, irreplaceable sensation of uniting families, seeing the tears of old people who finally learn about the fate of their relatives, and after several decades of unanswered questions, as well as institutional shrugs and indifference, see that the state actually cares.

-

Office of Search and Identification - identification work -

Office of Search and Identification - identification work -

Office of Search and Identification - identification work -

Office of Search and Identification - identification work -

Office of Search and Identification - identification work -

Office of Search and Identification - identification work -

Office of Search and Identification - identification work -

Office of Search and Identification - identification work

That job satisfaction, shared equally by the staff and a vast pool of volunteer helpers, also stems from the education opportunities. For a few years now, the Office has been running the "»Łączka« and other search and identification sites" project, which draws primary and secondary school students into the intricacies of the excavation work, while providing one-of-the-kind history lessons. It started in the infamous burial place in Warsaw, where the communist regime hid its darkest secrets, but then spread to other similar sites throughout Poland.

-

Office of Search and Identification - commemoration and education -

Office of Search and Identification - commemoration and education -

Office of Search and Identification - commemoration and education -

Office of Search and Identification - commemoration and education -

Office of Search and Identification - commemoration and education -

Office of Search and Identification - commemoration and education -

Office of Search and Identification - commemoration and education -

Office of Search and Identification - commemoration and education

The combination of tangible results – the numbers of people brought from the shadows of history and introduced into history – with the job satisfaction makes it worthwhile, and proves that there’s more to the work of the IPN’s Office of Search and Identification than meeting the state’s legal obligations; when they claim to "reclaim their own", they mean it.