Abstract

Katyn is a symbol of the criminal policy of the Soviet system against the Polish nation. The present study aims to demonstrate the basic facts of Katyn massacre – the execution of almost 22,000 people: Polish prisoners of war in Katyn, Kharkov, Kalinin (Tver) and also other Polish prisoners (soldiers and civilians), which took place in the spring of 1940 in different places of the Soviet Ukraine and Belarus republics based on the decision of the Soviet authorities, that is the Political Bureau of All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) of March 5, 1940. This article refers not only to the massacre itself, but also its origin, historical processes and the lies accompanying Katyn massacre.

Keywords

Katyn massacre, Soviet policy, All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks).

The term ‘Katyn massacre’ refers to the execution in the spring of 1940 of almost 22,000 people: Polish prisoners of war in Katyn, Kharkov, Kalinin (Tver) and also prisoners (soldiers and civilians), in different places of the Soviet Ukraine and Belarus republics based on the decision of the Soviet authorities, that is the Political Bureau of All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) of March 5, 1940. The commonly used expression referring to the simultaneous murders at many locations includes only the name of one of them, where the bodies of the officers were buried. This is connected with the fact that, for almost half the century after these tragic events, the knowledge about people taken into captivity, or arrested and finally murdered based on the resolution of the Political Bureau of All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks), was limited to the information of the executions in Katyn1.

The widely understood term ‘Katyn massacre’ refers not only to the massacre itself, but also its origin, the lies accompanying it and attempts to judge those responsible for it.

1. The Soviet policy towards Poland and the Poles until 1939

The Katyn massacre committed by the People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs (the NKVD) in 1940 shows how the USSR policy aimed at destroying Poland’s statehood since it gained independence after World War I2. The Treaty of Riga, which was signed in 1921 by Poland, the Soviet Russia and Ukrainian People’s Republic of Soviets, ended the Polish-Soviet war of 1919–1920. Under this treaty, the Polish eastern border was established along the following line: Dzisna–Dokszyce–Slucz–Korzec–Ostrog–Zbrucz. The parties dismissed mutual territorial claims. However, the Bolsheviks, who treated the peace agreement as a concession which was forced by the military situation, did not give up their expansion plans to the West and maintained a hostile attitude towards Warsaw3.

After 1921, small, specially trained groups of Ukrainian and Belarusian Bolsheviks and the Red Army soldiers slipped across the border from the Soviet Russia. They attacked police stations, civilians, clerks and set fire to forests.

The Creation of the Border Protection Corps in 1924 gradually restricted the penetration of these agents and terrorists4.

Despite the fact that talks on the Polish-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact had been taking place since 1926, Moscow still expressed a hostile attitude towards the Second Polish Republic in the second half of the twenties, by supporting Lithuanian territorial claims towards Poland and considering Pilsudski’s government ‘fascist’. After the assassination of the USSR deputy, Piotr Wojkow, in 1927 by a Russian emigrant, the negotiations collapsed, and the Bolsheviks accused the Polish government of supporting Russian emigrant organizations5.

In 1932, a pact was signed in which parties rejected the idea of war as an international policy tool, accepted one another’s obligations and declared that if any party was attacked, no help would be offered to the aggressor. The pact was to be in force for three years, but in 1934 both the Bolsheviks and the Polish government decided to prolong this period to ten years in the face of the danger from Germany ruled by the Nazi party6.

One of the crucial factors which influenced the relations between Moscow and Warsaw was the situation of about one million Poles who, after the Treaty of Riga was signed, remained beyond the eastern border7. The USSR government created two ethnic regions for them: Julian Marchlewski Polish Autonomous District (Marchlewszczyzna) in Ukraine in 1925, and Feliks Dzierzynski Polish Autonomous District (Dzierzynszczyzna) in Belarus in 1932. The aim of the Bolsheviks’ policy in these districts was to form units which were to participate in the aggression against the Second Polish Republic in the future. The ‘national experiment’ was a failure because the inhabitants of both districts preserved national and Catholic traditions and in the 1930’s strongly opposed collectivization. In 1935 the decision to dissolve Marchlewszczyzna was announced. Based on the act of the Council of People’s Commissars of 28 April 1936, the deportation of masses of Marchlewszczyzna citizens to Siberia and Kazakhstan started8. According to final reports prepared by the NKVD, about 50,000 people were forced to leave their country. In 1938 Dzierzynszczyzna met with the same fate and it is estimated that about 20,000 people were deported.

During the years of the great terror 1937–1938, which affected the inhabitants of the whole USSR, an attack on the Poles who lived in the Soviet Ukraine and Belarus occurred. Based on the order issued on 11 August, 1937 by Nikolai Yezhov, an internal affairs commissar, the so-called Polish Operation of the NKVD began9. This meant arrests, and executions based on false accusations of spy and sabotage activities. From August 1937 till September 1938, 144,000 Poles were judged, among whom 111,000 were shot by the NKVD, and almost 30,000 were sent to labour camps or prisons after receiving five to fifteen year sentences10.

The hostility of the USSR authorities towards the Poles during the period between the wars originated, among other things, from the desire to take revenge for the defeat of the Red Army at the Polish-Bolshevik War in 1920 and preventing the army from advancing towards the west11.

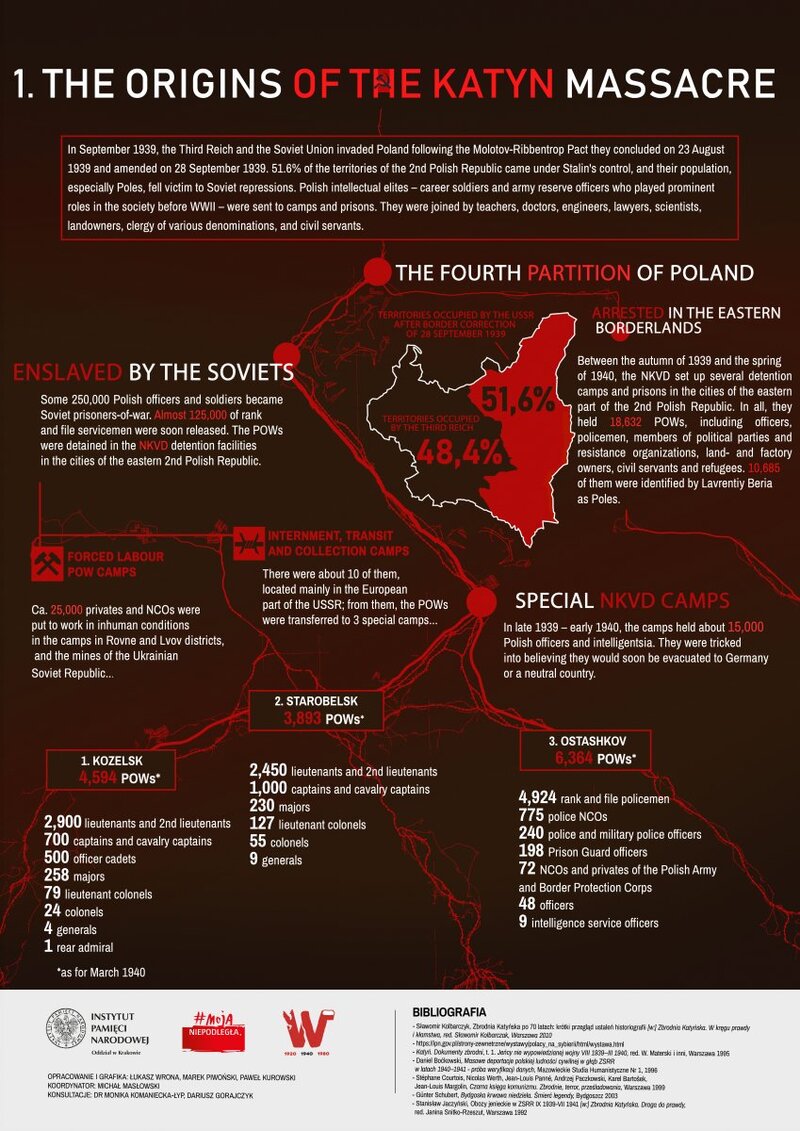

2. The Soviet invasion of Poland on 17 September 1939

In the morning of 17 September, 1939, between 600–650,000 soldiers and over 5,000 thousand Red Army tanks invaded the Second Polish Republic, which had been fighting against German aggression since 1 September12. On 23 August, 1939, the USSR and the Third Reich signed a pact, which was named the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact after its signatories, the ministers of foreign affairs of both countries. According to the confidential protocol of this non-aggression pact, the USSR’s sphere of influence was to extend approximately to the Narew, Vistula and San rivers. This state of affairs was confirmed in the treaty of 28 September and another protocol accompanying it, according to which German and Soviet parties committed themselves to fighting ‘Polish agitation’13.

The invasion of the Red Army took place at the time when the Polish forces were retreating eastwards before the Germans, after an unsuccessful attempt to maintain the territory to the Narew, Vistula nad San rivers. According to Edward Rydz-Smigly’s military plan, the remaining units were to gather at the so-called Romanian Bridgehead and continue defence until France and Great Britain launched an offensive in the West. They declared war on Germany on 3 September under their obligations towards Poland from before 1 September. As a result of the decision of 12 September, which was taken by the French-English Supreme Council of War, the allies did not take any military action, and the Red Army invaded Poland on the pretext that ‘the Polish country and its government ceased to exist’. Consequently, ‘the USSR had to take care of the people who lived in Western Ukraine and Western Belarus and their possessions’ as the Soviet propaganda referred to the eastern regions of the Second Polish Republic14.

The commander-in-chief of the Polish Army, Marshal Smigly-Rydz ordered the army to abstain from provocative operations against the Soviets and allowed the possibility of war in case ‘they invaded Poland or tried to disarm the detachments’15. Those instructions were issued in Kuty, where politicians, commanders, soldiers and civilians escaped across the bridge in Czeremosz to the Romanian bank.

People from Wilno (Vilnius) and Grodno and the group of Border Protection Corps resisted the enemy attack. The corps under Wilhelm Orlik-Rückemann’s command fought the battle of Szack against the 52 Rifle Division of the Red Army. By 25 September, as a result of Belarusian Front attack, the Soviets had gained possession of Wilno (Vilnius), Grodno, Brześć (Brest) on the River Bug and Suwalki. By 28 September, the soldiers of Belarusian Front had occupied Tarnopol, Dubno, Stanislawow, Lwów (Lviv) and Zamosc. The USSR gained control of over half of the territory of the Second Polish Republic16.

As soon as the Red Army crossed the border, it started to commit crimes: the massacre in Grodno and the assassination of General Jozef Olszyna-Wilczynski, the execution of marines of the Pinsk Flotilla in Mokrany, murders in Nowogrodek, Tarnopol and other places, the execution of the soldiers taken captive near Wilno (Vilnius), and also the arrest of defenders of Lwów (Lviv). This happened despite the agreement which guaranteed defenders of Lwów (Lviv) safe conduct towards the Romanian border17. Behind the army, operational-chekist groups of the NKVD followed, which murdered and arrested Polish people. These units formed the security apparatus in occupied places, gained control over the state archives, radio and telephone communications and they disarmed civilians. The units acted in accordance with the directive issued by the NKVD on ‘The Organisation of Work in Liberated Regions of Western Districts of Ukraine and Belarus’ of 15 September, 193918. About 230,000 soldiers and officers and thousands of military service representatives were taken captive by the Bolsheviks. In the majority of cases soldiers and officers did not oppose it. Privates were separated from officers who were transported to Kozelsk and Starobelsk. Policemen were transported mainly to Ostashkov19.

3. Camps

Kozelsk

Kozelsk camp was created in the buildings of a former monastery, the so-called Optina Hermitage. There were 4,594 captives there, about half of whom were reserve officers. There were also over 300 doctors, several hundred lawyers, engineers, teachers, 21 university lecturers, a lot of men of letters, journalists and feature writers. There was one woman among them: Second Lieutenant Pilot Janina Lewandowska, General Jozef-Dowbor-Musnicki’s daughter. The following people were kept there: Rear-admiral Ksawery Czernicki – chief of services of Naval Forces management; General Henryk Odrowaz-Minkiewicz

– the former commander of Border Protection Corps; General Mieczyslaw Smorawinski – commander of Corps District No 2 in Lublin; retired Generals Bronislaw Bohaterewicz and Jerzy Wolkowicki, and Professor Stanislaw Swianiewicz, who avoided death and played a significant role in uncovering Katyn massacre, its initiators and executors20.

Starobelsk

In Starobelsk the prisoners of war were kept in a former nunnery at 8 Kirov Street, in the buildings at 32 Kirov Street and 19 Wolodarski Street. There were 3,894 people there: a lot of scholars, priests, about 100 teachers and 400 doctors, several hundred lawyers and engineers, several dozen of men of letters and journalists, and also 8 generals: the defender of Lwów (Lviv) Franciszek Sikorski, Konstanty Plisowski, Stanisław Haller, Leonard Skierski, Leon Billewicz, Aleksander Kowalewski, Kazimierz Orlik-Lukoski and Piotr Skuratowicz21.

Ostashkov

The prisoners were kept in a former monastery on Stolobny Island on Seliger Lake, 11 kilometres from Ostashkov. Among the prisoners were the following: the State Police and Military Police officials, secret service and counter-espionage officials, the soldiers of the Border Protection Corps and the employees of the Prison Guard. There were also almost the whole staff of the Military Police Education Centre, among whom was Colonel Stanislaw Sitek. Ostashkov camp was the biggest of the three camps – there were about 6,570 prisoners of war just before it was disbanded in April 194022.

4. The massacre

Preparations for the massacre

From October 1939, the delegated NKVD officials from Moscow heard the prisoners, encouraged them to cooperate and collected data. Only a few of the prisoners agreed to collaborate. The commanding officers’ reports included opinions about hostile attitudes of the Poles and a minimal chance of them being useful to the USSR authorities23.

The decision to shoot the prisoners from Kozelsk, Starobelsk and Ostashkov was signed on 5 March, 1940 by seven members of the All- Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) authorities: Joseph Stalin, Lavrentiy Beria (proposer), Kliment Voroshilov, Vyacheslav Molotov, Anastas Mikoyan, Mikhail Kalinin and Lazar Kaganovich24. On 22 March, Beria issued an order ‘to empty the NKVD prisons in USSR and BSSR, that is in Western Ukraine and Western Belarus. The majority of those arrested Poles were officers and policemen25.

The lists of those sent to death were to be prepared and signed by Piotr Soprunienko, commander-in-chief of the Prisoners of War Board of People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs, which was created by the order of Beria in September 193926.

On 1 April, the first three lists of the 343 names were sent from Moscow to Ostaskhov camp. Later Soprunienko phoned the following commanding officers: Wasilij Korolew in Kozelsk, Aleksander Bierezkow in Starobelsk and Pawel Borisowiec in Ostaskhov in order to submit further lists of victims27.

5. Places of torture – cemeteries

Smolensk–Katyn

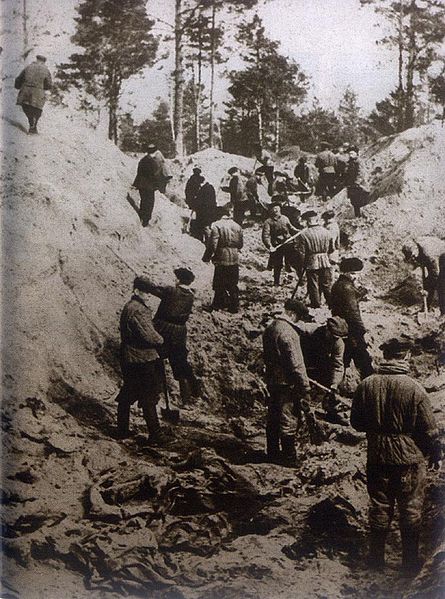

On 3 April, the first prisoners from Kozelsk were transported in cattle trucks through Smolensk to Gniezdovo, where smaller groups were transported by prison cars commonly called ‘czornyje worony’ (‘black ravens’) to the wilderness called Kozie Gory in Katyn Forest. The functionaries of the NKVD killed each person by shooting in the back of the head. By 11 May, 1940, 4,421 Polish citizens had been killed and buried in Katyn death pits. There is an assumption that some officers had been killed in Smolensk28.

Kharkov–Piatykhatky

The first group of prisoners from Starobelsk camp was transported to the headquarters of the Board of Kharkov NKVD district on 5 April 1940. Every night in the basement of the building in Dscherschinski Street executioners killed prisoners by shooting in the neck. The trucks carried the bodies to the pits in Forest Park in Kharkov, a kilometer and a half to Piatykhatky village. By 12 May 3,820 Polish citizens had been killed in Kharkov29.

Kalinin (Tver)–Miednoye

On 4 April, 1940, the NKVD started to send prisoners from Ostashkov to the headquarters of the Board of Kalinin NKVD district (today’s Tver) at 6 Soviet Street. The executions took place in the basements. The same method of killing was used: a shot to the neck. In the mornings trucks carried the bodies to the pits in Miednoye village, 30 kilometers further away. By 22 May, 1940, 6,311 Polish citizens had been killed in Kalinin. What is worth mentioning when it comes to the Katyn lie, is that the territory of Miednoye cemetery has never belonged to Germany30.

Polish authorities built war cemeteries at the places where the officers’ bodies had been buried. The cemeteries were officially opened in the year 2000. (in Kharkov on 17 June, in Katyn on 28 July and on 2 September in Miednoye)31.

Survivors

Only 395 people from the three camps survived. Some of them owed their rescue to pure chance. Several people were willing to fight on the Soviet side in case of German invasion. There were also agents among them, the same ones as the NKVD had in the camps. The officers who were arrested in the camps and transported to NKVD Lubyanka prison in Moscow also managed to escape death in the summer of 194032.

6. Ukrainian list, Belorusian list

The NKVD kept several thousand arrested officers, clerks, judges, prosecutors, political and social activists in prisons in the so-called Western Ukraine and Western Belarusia. 7,300 of them were put to death. There were 3,435 names of people on the so-called Ukrainian list, which was given to Poland by the Security Service of Ukraine in 1994. The people were killed after being transported, among others, from Lwów (Lviv), Rowne, Luck, Tarnopol, Stanislawow and Drohobycz to Kiev, Kharkov and Cherson. The data of the victims – about 3,870 prisoners transported from Pinsk, Brest, Baranowicze and Wilejka to Minsk – from the so-called Belarusian list have never been revealed and attempts by the Polish authorities to make the archives available have been unsuccessful so far33.

Ukraine – Bykivnia

At least 1,980 people people from the Ukrainian list were killed and buried in Bykivnia village near Kiev, where about 150 thousand NKVD victims of various nationalities were buried. When the Ukrainian authorities passed the information about Bykivnia cemetery to Warsaw in 2006, both countries started to study it34. The dog tag found in 2007 is considered to be the most important piece of evidence concerning the burial of Polish officers. The dog tag, which was a small piece of metal with soldiers’ personal data, was worn around the neck by them so that they could be identified in case they were injured or killed. The dog tag which was found in the grave in Bykivina had been made according to the standard from the year 1939, and belonged to Company Sergeant Jozef Naglik. On the comb unearthed were the names of the four soldiers, among whom was the name of Lieutenant-Colonel Bronislaw Szczyradlowski. The names Naglik and Szczyradlowski are on the so-called Ukrainian list. The Polish War Cemetery in Bykivnia was opened on 21 September, 201235.

Belarus – Kuropaty

In 1988, mass graves were discovered in Kuropaty Forest, in the suburbs of Minsk, where the NKVD buried between 100–200,000 Belarusians, Jews and people of various nationalities, including the Poles. The things found in the three mass graves indicate that they must have come from Poland or Western Europe36, for example a comb on which a prisoner had scratched Polish words: ‘Difficult prisoner’s moments. Minsk, 25.4.1940. Thinking about you drives me crazy. I have started to cry – a difficult day.’ This shows that, firstly, the Poles were buried there, and, secondly, they were in Minsk prison at the time when the NKVD carried out Katyn massacre37. However, it is impossible to find out the personal data of the owner of the comb and even if it were possible, one cannot compare them with the Belarusian list, which is still unknown to the Polish side. The Belaursian authorities claim that those who are buried there were murdered by the Germans, and make careful research difficult. In the year 2013, the Centre for Polish-Russian Dialogue and Understanding made a reconstruction of part of the so-called Belarusian Katyn list and created a list of 98 names. This was done by comparing the list of the people missing in the north-east districts of the Second Polish Republic in 1939 and 1940 with the NKVD convoy list of the people transported to Minsk prison in the years 1939–194038.

7. To exterminate Polish elites

There are mass graves in the whole area of the former Soviet Union. Stalin and other leading Bolshevik activists before him ordered the elimination of whole social classes – Russian intelligence and rich farmers, the so-called kulaks; superior servicemen and workers; aristocrats and their servants. They sentenced members of different professions to death, for example, doctors and generals and exterminated people of various nationalities: Russians, Poles, Ukrainians, Belarusians, Volga Germans, Crimean Tatars, Finns, Estonians, Latvians, Chinese – the list is endless39.

The massacre committed in the spring of 1940 was carefully considered and organized. The aim of the communist party was the extermination of those social groups which had been building the bases of the modern Polish nation since the mid-nineteenth century40.

A modern collective national consciousness was developed. This was possible thanks to the intellectual elite’s work on improving the conditions of life among peasantry, industrial workers or craftsmen and educated people’s attempts to involve those from lower classes of society in social life. Owing to the landed gentry’s and intellectual elite’s, care and effort to continue Polish traditions and culture were of interest to more and more social layers of Poles. The burghers, which was becoming richer and richer, developed modern industry by creating economic structures, on which – Poland reborn after the partition – built its economy41.

The social classes which remained passive during the uprisings in the 19th century took an active part in the fight for independence. After Poland gained independence in 1918, subsequent generations of intellectual elite created structures of an independent country, which was developing in all spheres of life42.

By carrying out the Katyn massacre, the Soviets got rid of large numbers of teachers, doctors, industrialists, engineers, humanists, writers, scholars, and also a lot of professional officers: the elites capable of rebuilding the country. Polish people who were a threat to the plans of the conquest of Poland, because they were determined to oppose the annexation of their country by Moscow and suspected in being involved in any anti-Soviet conspiracy found themselves in the hands of the NKVD. Mobilized reserve officers, not only the Poles, but also Ukrainians, Belarusians, Jews, Tatars and people of various nationalities living in the Second Polish Republic constituted over half of the victims43.

The plan of the destruction of people in the eastern part of the Polish Republic also included forced deportations, which were organized by the NKVD to faraway places in the USSR. The first of them took place from 9 to 11 February, 1940 and included, among others, military settlers, civil servants, workers of the forest services and Polish State Railways. The second deportation took place from 12 to 14 April, 1940. It included family members of those considered to be enemies of communism: office workers, police and prison officers, teachers, social activists, captives’ families and those repressed by the NKVD and killed in Katyn massacre. On 28 and 29 June, 1940, war refugees from central Poland were deported. The fourth deportation took place in May and June 1941. It included intellectuals, captives, labourers, craftsmen, families of railway workers and of those arrested since autumn 1940. The captives were deported to different republics of the USSR: Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Tajik, Turkmen, Uzbek, and also Russian (for example to Siberia). According to the Soviet documents that have been published so far, the number of Polish people deported in the years 1940–1941 is at least 309–327,000 citizens44.

8. Search for Polish officers and Stalin’s lies

The last pieces of news that the families received from the prisoners were from the beginnings of March 1940. Later, the NKVD denied any information. At the same time, the post started to return the letters to the officers sent by their families from the General Government45.

After the German invasion of the USSR, the Polish-Soviet relations were re-established, after they had been broken off on 17 September, 1939. On 30 July, 1941, Sikorski-Majski Pact was signed by the prime minister of the Polish government-in- exile and Moscow ambassador in London. Under this pact an army was to be formed, which would consist of the Poles staying in the USSR. It also provided – as it was called – the amnesty for all citizens of the Republic of Poland, who were, at that time, ‘deprived of freedom in the USSR, either as prisoners of war or according to any other corresponding rules’46.

The commander-in- chief in exile appointed General Wladyslaw Anders, who was released from Lubyanka prison in Moscow, the commander of Polish Armed Forces in the USSR. The former prisoners of gulags and also the Poles living in the Soviet Union traversed long distances in very difficult conditions in order to reach Tatiszczew near Saratow, Buzuluk and Totskoye (Orenburg district), where those ready to join Anders’ Army gathered47. All the people who arrived, both from the distant north and Siberia and from the European part of the empire asked about their commanders. Cavalry Captain, Jozef Czapski, the survivor of Starobelsk camp, a writer and painter and also a representative on the matter of the missing people, had gathered information about the Poles staying in the USSR and interceded with the Soviets. In the autumn of 1941, General Anders passed the authorities in Moscow a list of officers who were taken captive by the Red Army in 1939 and could be in gulags. A high number of the missing people, which was estimated to be about 15,000 at that time, excluded their accidental arrest in labour camps. Anders mentioned this during the conversation with Jozef Stalin and received the following reply: ‘They fled to Manchuria’48

9. The Germans discover the graves in Katyn

After the German invasion of the Soviet Union, the Germans occupied Smolensk area from July 1941 to September 1943. On 13 April, 1943, the radio in Berlin announced that mass Polish graves had been discovered in Katyn49. Since the end of March the Germans had been carrying out exhumations under the direction of Professor Gerhard Buhtz, the director of Forensic Medicine and Criminology Institute in Breslau (Wroclaw after the war). Further lists containing the names of the identified victims started to appear in the Polish-language German newspapers which were published in the General Government. Immediately, Stalin accused the Germans of this mass murder50.

The Germans tried to make use of the facts revealed, and on 16 April they invited the International Red Cross and chose inhabitants of the General Government to participate in the exhumations and examinations51.

The next day, General Sikorski’s government asked the International Red Cross for help with the examination; they did this independently of the German appeal, but Stalin used this as an excuse to accuse the Polish government-in-exile of collaboration with the Third Reich. This was the way in which the official Soviet newspaper Pravda (Truth) described the attitude of the Polish authorities. On 25 April, 1943, the Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs, Molotov, gave the Polish ambassador in Moscow a note saying that the USSR government had decided to ‘break off the relations with the Polish government’52.

Meanwhile, the International Red Cross replied that it would explain the circumstances of the executions on condition that all the parties concerned asked it to discover the truth. Moscow refused to participate. Thus, the Germans invited an independent committee consisting of 12 leading specialists in forensic medicine from the whole of Europe to the place of the massacre. The experts were in Katyn from 28 to 30 April. The statement that the experts issued dispelled all the doubts as to who was responsible for the massacre, namely, the executions took place at the time when Smolensk area was under the Soviet rule53.

At the same time the Technical Committee of the Polish Red Cross worked under the leadership of general secretary of the Polish Red Cross executive board Kazimierz Skarzynski. The committee consisted, among others, of the following people: Dr Marian Wodzinski, an expert in forensic medicine from Jagiellonian University, and priest Stanislaw Jasinski, the representative of Metropolitan Bishop of Krakow sent by the Church. The Polish government and secret authorities allowed another group of Polish people to go to Katyn. Among them were the writers: Ferdynand Goetel and Jozef Mackiewicz.

The German version of the events was supported by different circumstances, for instance the age of the trees planted on the graves before 1941, so the massacre must have been carried out by the Soviets, and also specific changes in the state of the corpses due to which it was possible to say that they had been there since 1940.

By 3 June, 1943 over 4,100 bodies had been removed, and Dr Wodzinski identified 2,800 of them. After the delegation arrived in the General Government, the Germans tried to force the Polish Red Cross to issue an announcement about Katyn, but the Poles did not want to be used for the purposes of German propaganda54.

10. Extermination and repressions of the Poles in the Third Reich

While the NKVD was killing Polish captives, the Germans were putting their carefully prepared plan to destroy Polish intellectual elite into action. As early as during the September campaign in 1939, six special squads (Einsatzgruppen) of Security Police (SiPo) and Security Service (SD) and an independent operational office were to perform an action against the Polishness. The aim of the actions code-named Tannenberg was to garrison Polish territories captured by the Wehrmacht55. The purpose of Intelligenzaktion56, part of which was Tannenberg, was to exterminate or send to labour camps all the people around whom an opposition against German oppression could be formed. The action was performed by Einsatzgruppen and, from November 1939, by permanent police outposts and Security service. As early as during the September campaign in 1939, they killed about 20,000 people considered enemies of the Third Reich, who were, among others, the participants of Silesian uprisings and Wielkopolska uprising.

On 6 November, 1939, a few days after the General Government was established from four districts: Warsaw, Radom, Lublin, Krakow (Galicia and Lwów (Lviv) were annexed in 1941), the Germans intensified the Intelligenzaktion operation. One of its parts was Sonderaktion Krakau (German: special action Krakow), which ended by arresting 183 people, for example, 144 academics from Jagiellonian University, 21 from AGH University of Science and Technology, 3 from Business Academy, 1 person from Catholic University of Lublin, and 1 person from Stefan Batory University in Wilno (Vilnius). The scholars were transported to Sachsenhausen concentration camp57.

One of the parts of Intelligenzaktion was also an action called Akcja AB (Außerordentliche Befriedungsaktion – German: extraordinary action of pacification; AB Action), which was carried out in the General Government especially intensively from April till July 1940. The aim of the action was to destroy the communities capable of organizing resistance: teachers, doctors, Catholic priests, judges, political and social activists and those suspected of participating in underground organisations. About 3,500 Polish people were killed then58. By July 1940, over 100,000 teachers, priests, landowners, lawyers, retired military men, political and social activists had become victims of Intelligenzaktion.

The matters related to the exchange of people between the territories occupied by the Germans and the Soviets and presumably the destruction of Polish elites were discussed during mutual conferences organized by the Gestapo and NKVD in Zakopane and Krakow between February and April 194059.

11. Katyn lie

The situation on the eastern front made Germany try to reconcile with the Poles. The massacre discovered by the Germans was to be used for disgracing Stalin, and consequently, making the anti-German coalition break up or at least weaken. The governments of the USA and Great Britain knew the truth, but were not interested in giving it wide publicity because this threatened the alliance with Moscow against the war with Hitler60.

Stalin used Polish communists for his purposes: on 28 April, 1943, Wanda Wasilewska accused Germany of committing the crime. She did this in her speech, which was later published in Izvestia. Next the leadership of Polish Workers’ Party did the same61.

In January 1944, the Soviets made another attempt to distort the truth: Special Committee under the leadership of Nikolay Burdenko went to Smolensk district, which was recaptured in September 1943. They carried out “re-assessment” for a few days in January 1944, and stated that the Germans were responsible for the massacre. It was then that a documentary and a report for the communist propaganda were produced. Again, Polish communists supported the Soviets: Wanda Wasilewska and Jerzy Borejsza spread Burdenko’s version in the Soviet press. Zygmunt Berling, the commander of the First Polish Army organized by Stalin, did the same62.

When the Germans left Krakow, retreating from the Red Army, the NKVD started to search for the people participating in the exhumation and examination of the evidence discovered in the death pits in Katyn. In March 1945, Dr Jan Robel and his co-workers were arrested. They had been examining the things dug up in Katyn and delivered to Krakow. In June public prosecution service accused, among others, writer, Ferdynand Goetel, and Dr Marian Wodzinski of collaborating with the Germans. Public prosecutor, Roman Martini, headed the investigation, and public prosecutor, Jerzy Sawicki, supervised it. Arrest warrants were issued for the witnesses, who first hid and then ran away abroad63.

In 1946, the Soviets unsuccessfully tried to include German war criminals in Nuremberg in the arraignment concerning killing “about 11,000 Polish officers in Katyn in 1941”. In the final document this matter was omitted. The reason was that it had unquestionably been established that the unit indicated by the Soviet prosecutor, the staff of the 537 Signal Regiment under the leadership of Colonel Ahrens, was stationed in the barracks a few kilometres from Katyn graves, but only from December 1941. Colonel Ahrens testified in Nuremberg as a witness64.

The authorities in Moscow tried to hide the truth for many years. Aleksander Szelepin, the chief of the Committee for State Security (KGB), suggested destroying the captives’ files to the Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, in 1959. The files “were kept in a sealed chamber”. According to the Russian sources, Khrushchev was to keep only the most important documents, which were hidden in a special file labelled number 165.

Katyn matter reappeared during the Cold War. In 1951, the US House of Representatives established a committee under the leadership of Ray John Madden. The investigation conducted by the committee met with strong opposition from the USSR and People’s Republic of Poland authorities. The report issued in July 1952 placed the blame unambiguously on the Soviets66.

In 1969, Ukrainian children accidentally found graves in Piatykhatky. The chief of KGB (Committee for State Security) and a future leader of the USSR, Jurij Andropov, ordered that the Poles’ remains be covered by slaked lime and buried. The documents describing these facts were found in 2009 by the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU)67.

In the 1970s, Moscow propaganda gave considerable publicity to the massacre of Belarusian people conducted by Germans in Chatyn in 1941. The similarity between the names of the places and their close location were used in order to mislead the western public opinion. A lot of politicians put flowers at the monument during their official visits to the USSR68.

After a short period of polemics with the Commission of the House of Representatives, silence followed – mentioning the word “Katyn” publicly was forbidden. It was not until the mid-seventies that the censorship in the People’s Republic of Poland allowed printing expressions like “shot by the Nazis in Katyn”’ or “was killed in Katyn”. The only date which could be given was the one after July 1941. At the same time, those who told the truth were punished. In the international area, the authorities of the USSR and People’s Republic of Poland opposed, among other things, the building of monuments reminding people of the Katyn massacre69.

Many years after the USSR officially accepted the responsibility for the Katyn crime, books denying the truth have been and still are being published in Russia. For example, Antirossijskaja podłost by Jurij Muchin was published in 2003. It spread the old lies about the Germans being to blame. Muchin also accused the Polish government in-exile of lengthening World War II and killing millions of people by revealing the crime. The consequence of the long-standing propaganda is the publication of the information about ‘the German crime in Katyn’ in the western press. One of the examples is the announcement of the film entitled Katyn by Andrzej Wajda, which appeared in a Swedish daily newspaper Dagens Nyheter. In 2008, the newspaper printed the information about ‘a Nazi massacre of the Polish officers in Katyn forest in 1940’70.

12. The guardians of memory

Stanisław Swianiewicz was transported with others prisoners by train from Kozelsk to Gniezdovo, near Katyn forest on 29 April, 1940. Arrested in the carriage, he saw through the slit Soviet buses transporting the other officers in the unknown direction. He was kept in other prisons, and finally freed under the terms of Sikorski-Majski pact. He reached the place where the Polish Armed Forces in the USSR were being formed, and he presented a detailed report. In 1951, he testified before a special committee of the US House of Representatives. His book In the Shadow of Katyn: Stalin’s terror71, which was published by the Literary Institute in Paris in 1976, contains his memories from the time when he was in gulags, prisons, and also the Embassy in Kuybyshev in 1942 when the Polish authorities were searching for traces of the 15,000 missing officers and policemen.

Jozef Czapski presented an account of his search for the missing officers in Wspomnienia Starobielskie (Reminiscences of Starobyelsk (1945)72 and later in the book In Inhuman Land73(1949).

In the People’s Republic of Poland, there were people who took a risk in order to preserve the memory of the NKVD victims. In 1978, Adam Macedonski, Andrzej Kostrzewski, Stanislaw Tor, Kazimierz Godlowski and Leszek Martini established a secret Katyn Institute in Poland74. In April 1979, just before the 39th anniversary of the tragedy, they revealed themselves. Until that time the members of the Institute had translated foreign language publications, among others, reports produced by ambassador O’Maley and by a special committee of the US Congress. They had also prepared the first 15 issues of the magazine „Biuletyn Katynski” („Katyn Bulletin”)75. The founders and co-workers of the Institute faced prosecutions and reprisals from the Security Service. The Institute was officially registered as Katyn Institute in Poland in 199176.

Priest Stefan Niedzielak and Wojciech Ziembinski started to create the Sanctuary of the Killed and Murdered in the East in Powazki Cemetery. Stefan Niedzielak was the chaplain of Home Army, a participant of the Warsaw Uprising and, from 1977, parish priest in Powazki Cemetery. He worked as the chaplain of families, which, in the 1980s, started to demand that the truth be revealed after half a century silence. On 31 July, 1981, the monument – Katyn cross – was erected on his initiative. The monument was destroyed on the same night by the Security Service. The Security Service threatened the priest in order to silence him. On the night of 19/20 January 1989, the priest died after receiving a blow to the head. His killers have still not been found77.

On 21 March, 1980, Walenty Badylak, a 76-year-old retired baker living in Krakow, set himself on fire in protest against communism and concealing the truth about Katyn. According to „Biuletyn Katyński”78, the files of the investigation into ‘committing suicide by Walenty Badylak, who was suspected of the crime under article 152 of the penal code’ were kept in the archives in Krakow District Prosecution Service. Article 15 of the penal code at that time imposed a custodial sentence from 6 months to 5 years for ‘manslaughter’, which was the way the communist prosecution service classified self-immolation. Walenty Badylak died from burns before the fire was extinguished. A metal plate with the word ‘Katyn’ was found with his body79.

13. Revealing the evidence about the crime by Moscow and reluctance to judge it

Political changes after the year 1989 and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 created – as it seemed then – an opportunity to begin a Polish investigation. However, the authorities in Warsaw decided that the investigation was within the jurisdiction of the law enforcement authorities of the country where the crime was committed. Public Prosecutor General, Jozef Zyto, applied to the USSR authorities to launch an investigation into the matter of Polish officers. After the initial refusal, the investigation was eventually undertaken in 199080.

It was on 13 April that the Soviet Union admitted for the first time that the massacre in Katyn was committed by the NKVD. In October 1992, the director of the Russian Federation State Archives, Rudolf Pikhoya, submitted the copies of the documents from the special file on the crimes committed in Katyn, Kharkiv and Kalinin (Tver). The documents were submitted to President Lech Walesa by the order of Russian President, Boris Yeltsin81.

The public opinion could read the interrogation protocols of several participants of the massacre called by the Russian law enforcement agencies to testify as witnesses. However, after a few years, the Russian Federation hardened its position and on 5 March, 2005, the Chief Military Prosecution Service announced that it had completed the investigation into the massacre on 21 September, 2004. On 11 March, 2005, the Chief Military Prosecution Service justified its decision by stating that killing Polish officers did not bear the stamps of genocide, but it was a common crime, so it expired. 116 out of 184 volumes of the investigation, including the decision of 21 September, 2004, were made confidential under the regulation of 21 December, 2004. Consequently, the files cannot be used, for example by Polish prosecutors82.

This met with a strong reaction from the family members of the victims, who having exhausted legal proceedings, lodged a few complaints to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg in the years 2007–2010. They demanded, among other things, that the justification of discontinuation of the Russian investigation be available to them because they did not accept the conclusion announced publicly by Russian prosecutors. The Russian reply was that they were under no obligation to explain what had happened to the Polish citizens who, according to them, ‘went missing’ ‘as a result of Katyn events’83.

Those complaints were handled together in the first instance by the European Court of Human Rights on 16 April, 2012. The judges decided that the crime in Katyn was a war crime, which does not expire. The Court also maintained that Russia treated the victims’ family members, who wanted to gain access to the documents, ‘inhumanely and humiliatingly’ by making the documents classified or not showing where the killed officers had been buried. Russia was also accused of making the documents unavailable to the European Court of Human Rights. Consequently, the Court was unable to decide whether the investigation was conducted thoroughly. The victims’ family members appealed against the sentence to the Grand Chamber. Supported by the state they challenge the decision of the Court that it was not able to examine whether the Russian investigation into Katyn massacre had been effective. The verdict is expected to be announced by the end of 201384.

On 30 November, 2004, the Institute of National Remembrance (the IPN) launched an investigation within its power to prosecute war crimes and crimes against mankind (including those committed by the communist regime) from the period between 1939 and 1990. The decision to launch the investigation was based on the assumption that Katyn Massacre was a war crime and a crime against mankind85.

By the end of 2012, 2,887 witnesses had been questioned, the majority of whom were the members of the victims’ families. The documents from the archives and public prosecution services had been gathered. While the prosecutors of the IPN were in Moscow in 2005, only 67 out of 183 volumes of the files of the investigation conducted by the Chief Military Prosecution Service of the Russian Federation were available to them for inspection. Although some of the documents were gradually declassified in the following years, there were 35 volumes of files at the end of 2012, which were still classified. These are probably fragments of the investigation and the decision to discontinue it. The Polish investigation is still being conducted86.

Translated by Iwona Ewa Waldzińska (State School of Higher Education in Oświęcim)

Notes

The intention of the authors was to summarize the most important facts connected with Katyn Massacre, which they gathered, among other things, when preparing the IPN educational portfolio ‘Katyn Massacre’ for Polish students and teachers. Its co-author is also D. Gorajczyk (IPN Kraków), „Zbrodnia Katyńska”, Kraków-Warszawa 2010.

A. Przewoźnik, J. Adamska, Katyń. Zbrodnia. Prawda. Pamięć, Warszawa 2010, p. 12; W. Materski, Na widecie. II Rzeczpospolita wobec Sowietów 1918–1943, Warszawa 2005, pp. 5–6; Polska i Ukraina w latach trzydziestych – czterdziestych XX wieku. Nieznane dokumenty z archiwów służb specjalnych, vol. 8: Wielki Terror: operacja polska 1937–1938 (Velykyi teror: pol’s’ka operatsija 1937–1938), a bilingual Polish-Ukrainian publication, collaborative work, Warszawa – Kijów 2010, part 1, pp. 57–59.

M. Iwanow, Pierwszy naród ukarany. Polacy w Związku Radzieckim 1921–1939, Warszawa– Wrocław 1991, pp. 74–75; W. Materski, Na widecie. II Rzeczpospolita wobec Sowietów 1918–1943, Warszawa 2005, pp. 98–116; about the difficulties with obeying the Treaty of Riga: ibid., pp. 117– 136; Kresy pamiętamy. Z Agnieszką Biedrzycką, ks. Romanem Dzwonkowskim, Januszem Kurtyką i Januszem Smazą rozmawia Barbara Polak, „Biuletyn IPN” (2009), no. 1–2, pp. 16–17, 20; N. Davies, Boże igrzysko. Historia Polski, Kraków 1999 (God’s Playground. A History of Poland, vol. 2: 1797 to the Present, Oxford, 1981), pp. 863–869.

W. Materski, Na widecie. II Rzeczpospolita wobec Sowietów 1918–1943, Warszawa 2005, pp. 257–261, 278–280, 421–422; M. Rataj, Pamiętniki 1918–1927, comp. J. Dębski, Warszawa 1965, p. 208.

W. Materski, Na widecie. II Rzeczpospolita wobec Sowietów 1918–1943, Warszawa 2005, pp. 295, 305–307, 310–324.

W. Materski, Na widecie. II Rzeczpospolita wobec Sowietów 1918–1943, Warszawa 2005, pp. 380–398, 443–446.

Kresy pamiętamy. Z Agnieszką Biedrzycką, ks. Romanem Dzwonkowskim, Januszem Kurtyką i Januszem Smazą rozmawia Barbara Polak, „Biuletyn IPN” (2009), no 1–2, p. 19.

H. Stroński, Nieudany eksperyment. Treść, formy i skutki sowietyzacji ludności polskiej na Ukrainie w latach dwudziestych i trzydziestych XX wieku, in: Polska droga do Kazachstanu. Materiały z międzynarodowej konferencji naukowej, Żytomierz 12–14 October 1996, T. Kisielewski, ed., Warszawa 1998, p. 7–23; H. Stroński, Koniec eksperymentu. Rozwiązanie Marchlewszczyzny i deportacje ludności polskiej do Kazachstanu w latach 1935–1936 w świetle nowych dokumentów archiwalnych, „Ucrainica-Polonica”, Kijów 2007, no. 1, pp. 201–220.

Polska i Ukraina w latach trzydziestych – czterdziestych XX wieku. Nieznane dokumenty z archiwów służb specjalnych, vol. 8: Wielki Terror: operacja polska 1937–1938 (Velykyi teror: pol’s’ka operatsija 1937–1938), a bilingual Polish-Ukrainian publication, collaborative work, Warszawa – Kijów 2010, part 1, pp. 257–263.

T. Snyder, Skrwawione ziemie, Warszawa 2011, pp. 111–126, (T. Snyder, Bloodlands. Europe between Hitler and Stalin, New York 2010); A. Paczkowski, Polacy pod obcą i własną przemocą, in: Czarna księga komunizmu. Zbrodnie, terror, prześladowania, collaborative work, Warszawa 1999, pp. 341–366 (The Black Book of Communism. Crimes, Terror, Repression, London 1999; Polska i Ukraina w latach trzydziestych – czterdziestych XX wieku. Nieznane dokumenty z archiwów służb specjalnych, vol. 8: Wielki Terror: operacja polska 1937–1938 (Velykyi teror: pol’s’ka operatsija 1937–1938), a bilingual Polish-Ukrainian publication, collaborative work Warszawa – Kijów 2010, part 1, pp. 63–71; M. Ellman, Stalin and Soviet Famine of 1932–33 Revisited, „Europe and Asia Studies” (2007), vol. 59, no 4, pp. 686–687; N. Pietrow, Polska operacja NKWD, „Karta” 1993, no. 11, pp. 24–45; One of the papers dealing with the Polish Operation of the NKVD is Rozstrzelać Polaków: ludobójstwo Polaków w Związku Sowieckim w latach 1937–1938: dokumenty z centrali, comp. T. Sommer, Warszawa 2010.

A. Paul, Katyń. Stalinowska masakra i tryumf prawdy, Warszawa 2010, p. 30 (Katyn: Stalin’s massacre and the Seeds of Polish Resurrection, New York 1991). Historyczne części książki autorstwa prof. Anny Marii Cienciały.

Agresja sowiecka na Polskę w świetle dokumentów. 17 września 1939, vol. 1: Geneza i skutki, vol. 2: Działania wojsk Frontu Ukraińskiego, vol. 3: Działania wojsk Frontu Białoruskiego, comp. C. Grzelak, S. Jaczyński, E. Kozłowski, Warszawa 1994–1996, passim; N. Davies, Boże igrzysko. Historia Polski, Kraków 1999 (God’s Playground. A History of Poland, vol. 2: 1797 to the Present, Oxford, 1981), p. 901; J. Łojek, Agresja 17 września 1939. Studium aspektów politycznych, Warszawa 1990, passim; W. K. Roman, J. Tucholski, Obóz w Starobielsku, in: Charków. Księga Cmentarna Polskiego Cmentarza Wojennego, comp. J. Ciesielski et al., Warszawa 2003, pp. XIII–XXIV.

Agresja sowiecka na Polskę 17 września 1939 w świetle dokumentów, vol. 1, Geneza i skutki agresji, E. Kozłowski, ed., Warszawa 1994, pp. 87–90; Z. S. Siemaszko, W sowieckim osaczeniu 1939–1943, Londyn 1991, pp. 17–21; R. Szawłowski, Wojna polsko-sowiecka 1939, vol. 2 – dokumenty, Warszawa 1997, p. 15; Katyn. A Crime Without Punishment, A. M. Cienciala, N. Lebedeva, W. Materski, eds., New Haven 2007, pp. 39–42.

Katyn. A Crime Without Punishment, A. M. Cienciala, N. Lebedeva, W. Materski, eds., New Haven 2007, pp. 21–22, 44–45; „Prawda”, no. 259, 18 September 1939; P. Wieczorkiewicz, Polska w planach Stalina w latach 1935–1945, in: W objęciach wielkiego brata. Sowieci w Polsce 1944–1993, K. Rokicki, S. Stępień, eds., Warszawa 2009, pp. 29–31.

Katyn. A Crime Without Punishment, A. M. Cienciala, N. Lebedeva, W. Materski, eds., New Haven 2007, p. 48; J. Łojek, Agresja 17 września 1939. Studium aspektów politycznych, Warszawa 1990, pp. 100–107; R. Szawłowski, Wojna polsko-sowiecka 1939, vol. 1 – monograph, Warszawa 1997, pp. 43–47; P. Wieczorkiewicz, Historia polityczna Polski 1935–1945, Warszawa 2005, p. 96.

Cz. Grzelak, Kresy w czerwieni. Agresja Związku Sowieckiego na Polskę w 1939 roku, Warszawa 1998, pp. 228–415; K. Liszewski, Wojna polsko-sowiecka 1939 r., Londyn 1988, p. 26; P. Wieczorkiewicz, Kampania 1939, Warszawa 2001, pp. 93–113; W przeddzień zbrodni katyńskiej: agresja sowiecka 1939 roku, M. Tarczyński, ed. „Zeszyty Katyńskie” (1999), no. 10.

J. W. Dyskant, Flotylla Rzeczna Marynarki Wojennej wobec agresji sowieckiej we wrześniu 1939 r., „Wojskowy Przegląd Historyczny” (1992), no. 3, pp. 3–33; K. Pindel, Obrona Narodowa 1937–1939, Warszawa 1979, p. 191; W. K. Roman, J. Tucholski, Obóz w Starobielsku, in: Charków. Księga Cmentarna Polskiego Cmentarza Wojennego, comp. J. Ciesielski et al., Warszawa 2003, pp. XV–XIX.

Śladem zbrodni katyńskiej, comp. Z. Gajowniczek, Warszawa 1998, pp. 17–19.

Katyn. A Crime Without Punishment, A. M. Cienciala, N. Lebedeva, W. Materski, eds., New Haven 2007, pp. 25–35; A. Przewoźnik, J. Adamska, Katyń. Zbrodnia. Prawda. Pamięć, Warszawa 2010, pp. 49–72; Z. S. Siemaszko, W sowieckim osaczeniu 1939–1943, Londyn 1991, pp. 36–57.

S. Swianiewicz, W cieniu Katynia, Warszawa 1990, p. 97 (In the Shadow of Katyn: Stalin’s terror, Pender Island 2002); J. K. Zawodny, Zbrodnia Katyńska, in: Księga Cmentarna Polskiego Cmentarza Wojennego w Katyniu, comp. J. Kiński et al., Warszawa 2000, pp. XXI–XXX; Lista jeńców obozu w Kozielsku zamordowanych w Lesie Katyńskim w kwietniu i maju 1940 r. spoczywających na polskim Cmentarzu Wojennym w Katyniu, in: Księga Cmentarna Polskiego Cmentarza Wojennego w Katyniu, comp. J. Kiński et al., Warszawa 2000, pp. 44, 93, 343, 404, 578; the whole cemetery book is also available on the Internet: www.10pul.idl.pl/pliki/katyn/katyn_ksiega_cmentarna_cz1. pdf, www.10pul.idl.pl/pliki/katyn/katyn_ksiega_cmentarna_cz2.pdf, www.10pul.idl.pl/pliki/katyn/ katyn_ksiega_cmentarna_cz3.pdf (03.04.2013); A. Przewoźnik, J. Adamska, Katyń. Zbrodnia. Prawda. Pamięć, Warszawa 2010, pp. 72–76; J. K. Zawodny, Death in the Forest. The Story of Katyn Forest Massacre, London 1971, pp. 101–162. General Jerzy Wolkowicki and Stanislaw Swianiewicz survived.

W. K. Roman, J. Tucholski, Obóz w Starobielsku, in: Charków. Księga Cmentarna Polskiego Cmentarza Wojennego, comp. J. Ciesielski et al., Warszawa 2003, pp. XI–XIII, XXIV–LII; Jeńcy obozu w Starobielsku zamordowani w siedzibie charkowskiego Zarządu NKWD w kwietniu i maju 1940 r. spoczywający na Polskim Cmentarzu Wojennym w Charkowie, in: Charków. Księga Cmentarna Polskiego Cmentarza Wojennego, comp. J. Ciesielski et al., Warszawa 2003, pp. 31, 158, 252, 315, 420, 483, 488, 493; the whole cemetery book is also available on the Internet: www. radaopwim.gov.pl/media/pliki/Ksiega_Cmentarna_Charkow.pdf (03.04.2013); A. Przewoźnik, J. Adamska, Katyń. Zbrodnia. Prawda. Pamięć, Warszawa 2010, pp. 76–81; E. Gruner-Żarnoch, Starobielsk w oczach ocalałych jeńców, Dziekanów Leśny 2009.

Z. Gajowniczek, B. Gronek, Więźniowie Ostaszkowa, in: Miednoje. Księga Cmentarna Polskiego Cmentarza Wojennego, comp. Z. Gajowniczek et al., vol. 1–2, Warszawa 2006, p. XXVI– XXXIV; Jeńcy obozu w Ostaszkowie zamordowani przez NKWD wiosną 1940 r. w Kalininie, spoczywający na Polskim Cmentarzu Wojennym w Miednoje, in: Księga Cmentarna Polskiego Cmentarza Wojennego, comp. Z. Gajowniczek et al, vol. 1–2, Warszawa 2006, p. 808; the whole cemetery book is also available on the Internet: www.radaopwim.gov.pl/media/pliki/Ksiega_Cmen tarna_Miednoje_Tom1.pdf, www.radaopwim.gov.pl/media/pliki/Ksiega_Cmentarna_Miednoje_Tom2.pdf (03.04.2013); A. Przewoźnik, J. Adamska, Katyń. Zbrodnia. Prawda. Pamięć, Warszawa 2010, pp. 81–85.

A. Paul, Katyń. Stalinowska masakra i tryumf prawdy, Warszawa 2003, pp. 75–86 (Katyn: Stalin’s massacre and the Seeds of Polish Resurrection, New York 1991); N. Lebedeva, The Tragedy of Katyn, “International Affairs”, Moscow 1990; N. Lebiediewa, Katyń – zbrodnia przeciwko ludzkości, Warszawa 1997.

Katyń. Dokumenty ludobójstwa, dokumenty i materiały archiwalne przekazane Polsce 14 października 1992 r., trans. W. Majerski, Warszawa 1992, pp. 27–28, 35–42; Katyn. A Crime Without Punishment, A. M. Cienciala, N. Lebedeva, W. Materski, eds., New Haven 2007, pp. 118–120.

Katyn. A Crime Without Punishment, A. M. Cienciala, N. Lebedeva, W. Materski, eds., New Haven 2007, p. 154–156; Listy katyńskiej ciąg dalszy. Straceni na Ukrainie. Lista obywateli polskich zamordowanych na Ukrainie na podstawie decyzji Biura Politycznego WKP (b) i naczelnych władz państwowych ZSRR z 5 marca 1940 roku, Warszawa 1994.

S. Jaczyński, Zagłada oficerów Wojska Polskiego na Wschodzie, wrzesień 1939 – maj 1940, Edition II, Warszawa 2006; A. Głowacki, Jeńcy września w niewoli sowieckiej 1939 r. Przed zagładą, „Zeszyty Katyńskie”, no. 10 (1999), pp. 24–68.

Katyn. A Crime Without Punishment, A. M. Cienciala, N. Lebedeva, W. Materski, eds., New Haven 2007, pp. 157–159.

Księga Cmentarna Polskiego Cmentarza Wojennego w Katyniu, comp. J. Kiński et al., Warszawa 2000; A. Paul, Katyń. Stalinowska masakra i tryumf prawdy, Warszawa 2003, pp. 103– 116 (Katyn: Stalin’s massacre and the Seeds of Polish Resurrection, New York 1991); For Stanisław Swianiewicz’s report, refer to The Katyn Forest massacre. Hearings before the Select Committee to conduct an investigation of the facts evidence and circumstances of the Katyn Forest massacre, Washington 1951–1952, part. 4, p. 111; Zbrodnia katyńska w świetle dokumentów (including the foreword by general W. Anders), Londyn 1982, pp. 47–49 (The Crime of Katyn: Facts and Documents, London 1989).

Katyń. Dokumenty zbrodni, A. Gieysztor, R.G. Pichoja, eds., vol. 2: Zagłada, A. Gieysztor, W. Kozłow, eds., Warszawa 1998, pp. 475, 486, 489; Charków. Księga Cmentarna Polskiego Cmentarza Wojennego, comp. J. Ciesielski et al., Warszawa 2003; J. Morawski, Ślad kuli, Warszawa–Londyn 1992, pp. 96–97, 104–128.

Z. Gajowniczek, B. Gronek, Więźniowie Ostaszkowa, in: Miednoje. Księga Cmentarna Polskiego Cmentarza Wojennego, comp. Z. Gajowniczek et al., vol. 1, Warszawa 2006, pp. XXXIX– XLV; Miednoje. Księga Cmentarna Polskiego Cmentarza Wojennego, comp. Z. Gajowniczek et al., vol. 1–2, Warszawa 2006; J. Morawski, Ślad kuli, Warszawa–Londyn 1992, pp. 95–96; Zeznanie Tokariewa, „Zeszyty Katyńskie” (1994), no. 3.

A. Przewoźnik, J. Adamska, Katyń. Zbrodnia. Prawda. Pamięć, Warszawa 2010, pp. 449–528; A. Przewoźnik, Cmentarz w Katyniu, in: Księga Cmentarna Polskiego Cmentarza Wojennego w Katyniu, comp. J. Kiński et al., Warszawa 2000, pp. LIII–LX; A. Przewoźnik, Cmentarz w Charkowie, in: Charków. Księga Cmentarna Polskiego Cmentarza Wojennego, comp. J. Ciesielski et al., Warszawa 2003, pp. LVII–LXXV; A. Przewoźnik, Cmentarz w Miednoje, in: Miednoje. Księga Cmentarna Polskiego Cmentarza Wojennego, comp. Z. Gajowniczek et al., vol. 1–2, Warszawa 2006, pp. LI–LXXVII; Charków, Katyń, Miednoje. Polskie cmentarze wojenne. Polish war cemetery. Polskoe voennoe memorialnoe kladbishche, A. Spanili, ed., Gdynia 2000.

N. Lebiediewa, Katyń – zbrodnia przeciwko ludzkości, Warszawa 1997, p. 171; Katyń. Dokumenty zbrodni, A. Gieysztor, R.G. Pichoja, eds., vol. 2: Zagłada, A. Gieysztor, ed., W. Kozłow, Warszawa 1998, p. 351; A. Przewoźnik, J. Adamska, Katyń. Zbrodnia. Prawda. Pamięć, Warszawa 2010, p. 120; J. K. Zawodny, Zbrodnia Katyńska, in: Księga Cmentarna Polskiego Cmentarza Wojennego w Katyniu, comp. J. Kiński et al., Warszawa 2000, p. XL.

J. Gorelik, Kuropaty. Polski ślad, Warszawa 1996; S. Kalbarczyk, Białoruska lista katyńska – brakujący element prawdy o Zbrodni Katyńskiej, „Zeszyty Katyńskie”, no. 23 (2008), pp. 135– 145; A. Przewoźnik, J. Adamska, Katyń. Zbrodnia. Prawda. Pamięć, Warszawa 2010, pp. 532–562.

A. Przewoźnik, J. Adamska, Katyń. Zbrodnia. Prawda. Pamięć, Warszawa 2010, pp. 546–550.

Polski Cmentarz Wojenny w Kijowie-Bykowni (Czwarty Cmentarz Katyński), Warszawa 2012.

S. Kalbarczyk, Białoruska lista katyńska – brakujący element prawdy o Zbrodni Katyńskiej, „Zeszyty Katyńskie” (2008), no. 23, pp. 135–145.

J. Gorelik, Kuropaty. Polski ślad, Warszawa 1996.

www.cprdip.pl/main/index.php?id=fragment-rekonstrukcji-bialoruskiej-listy-katynskiej (03.04.2013).

A. Paul, Katyń. Stalinowska masakra i tryumf prawdy, Warszawa 2010, pp. 47–52, 101–109, 111–127, 129–131 (Katyn: Stalin’s massacre and the Seeds of Polish Resurrection, New York 1991); R. Pipes, Komunizm, Warszawa 2008, pp. 59–63, (Communism, London 2001); N. Davies, Europa. Rozprawa historyka z historią, Kraków 1998, pp. 989, 1020–1025 (N. Davies, Europe. A History, Oxford 1996); P. Johnson, Historia świata (od roku 1917), London 1989, pp. 76–80 (History of the Modern World: From 1917 to the 1980’s, London 1983).

J. Czapski, Wspomnienia starobielskie, in: Na nieludzkiej ziemi, Kraków 2011, pp. 10–12, 17– 21, 23–33 (Ricordi di Starobielsk, Roma 1945; Souvenirs de Starobielsk, Paris 1987); J. Mackiewicz, Sprawa mordu katyńskiego. Ta książka była pierwsza, Londyn 2009, p. 167 (Katyn – ungesühntes Verbrechen, Zurich 1949; The Katyn Wood Murders, London 1951); T. Snyder, Skrwawione ziemie, Warszawa 2011, pp. 147, 176 (T. Snyder, Bloodlands. Europe between Hitler and Stalin, New York 2010); A. Paul, Katyń. Stalinowska masakra i tryumf prawdy, Warszawa 2010, pp. 13–14, 96–99 (Katyn: Stalin’s massacre and the Seeds of Polish Resurrection, New York 1991); A. Przewoźnik, J. Adamska, Katyń. Zbrodnia. Prawda. Pamięć, Warszawa 2010, pp. 11–15, 75– 82.

H. Wereszycki, Historia polityczna Polski 1864–1918, Kraków 1981, pp. 7–9, 322–329.

By using the example of Markowa, Szpytma M. describes how big influence Katyn massacre had on even small communities, for example village communities Pars pro toto. Katyńczycy z Markowej – major Antoni Fleszar i kapitan Władysław Ciekot, „Zeszyty Historyczne WiN-u” no. 32–33 z XII 2010, pp. 91–113; after the article was published, it turned out that another victim was connected with this place, Captain Franciszek Michnar, whose name is on the Ukrainian Katyn List.

G. Hryciuk, Victims 1939–1941: The Soviet Repressions in Eastern Poland, in: E. Barkan, E. A. Cole, K. Struve, ed., Shared History – Divided Memory: Jews and Others in the Soviet-Occupied Poland, Leipzig 2007, pp. 179–180; Katyn. A Crime Without Punishment, A. M. Cienciala, N. Lebedeva, W. Materski, eds., New Haven 2007, p. 26; K. Jasiewicz, Drugie dno zbrodni katyńskiej, „Uważam Rze. Historia” 2012, no. 1.

W. Materski, Katyń. Od kłamstwa ku prawdzie, Warszawa 2012, pp. 67–74; A. Przewoźnik, J. Adamska, Katyń. Zbrodnia. Prawda. Pamięć, Warszawa 2010, pp. 168–177; A. Paul, Katyń. Stalinowska masakra i tryumf prawdy, Warszawa 2010, pp. 117–133, 150–157, 167–179 (Katyn: Stalin’s massacre and the Seeds of Polish Resurrection, New York 1991); before the Russian archives were opened, the number of deported people was estimated to be approximately 1,200,000 according to the Polish emigration historiography, refer to: J. K. Zawodny, Death in the Forest. The Story of Katyn Forest Massacre, London 1971, p. 5 (based on: Polskie Siły Zbrojne w Drugiej Wojnie Światowej, Komisja Historyczna Polskiego Sztabu głównego w Londynie, London 1950– 1951; nowadays some historians emphasize that the number of people deported has been calculated based only on the Soviet documents published so far, and it may be much bigger).

A. Przewoźnik, J. Adamska, Katyń. Zbrodnia. Prawda. Pamięć, Warszawa 2010, pp. 177– 178; J. Mackiewicz, Sprawa mordu katyńskiego. Ta książka była pierwsza, Londyn 2009, pp. 157, 219–220 (Katyn – ungesühntes Verbrechen, Zurich 1949; The Katyn Wood Murders, London 1951).

A. Paul, Katyń. Stalinowska masakra i tryumf prawdy, Warszawa 2010, pp. 188–191 (Katyn: Stalin’s massacre and the Seeds of Polish Resurrection, New York 1991); Stosunki Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej z państwem radzieckim 1918–1943. Wybór dokumentów, comp. J. Komaniecki, Warszawa 1991, p. 245; J. K. Zawodny, Death in the Forest. The Story of Katyn Forest Massacre, London 1971, p. 6.

W. Anders, Bez ostatniego rozdziału. Wspomnienia z lat 1939–1946, part 1, Lublin 1988, p. 76.

Zbrodnia katyńska w świetle dokumentów (including the foreword by general W. Anders), Londyn 1980, pp. 64–84 (The Crime of Katyn: Facts and Documents, London 1989); J. Mackiewicz, Sprawa mordu katyńskiego. Ta książka była pierwsza, Londyn 2009, pp. 87–104 (Katyn – ungesühntes Verbrechen, Zurich 1949; The Katyn Wood Murders, London 1951); W. Anders, Bez ostatniego rozdziału. Wspomnienia z lat 1939–1946, part 1, Lublin 1988, pp. 85–89, 119; J. Czapski, Na nieludzkiej ziemi, Kraków 2011, pp. 71–72, 88–101, 137–183 (The Inhuman Land, London 1987; La terre inhumaine, Lausanne 1979, Unmenschliche Erde Frankfurt a.M 1969) oraz Prawda o Katyniu, in: Na nieludzkiej ziemi, Kraków 2011, pp. 361, 365–361; J. K. Zawodny, Death in the Forest. The Story of Katyn Forest Massacre, London 1971, pp. 6–11; A. Przewoźnik, J. Adamska, Katyń. Zbrodnia. Prawda. Pamięć, Warszawa 2010, pp. 178–195; T. Snyder, Skrwawione ziemie, Warszawa 2011, pp. 174–175 (T. Snyder, Bloodlands. Europe between Hitler and Stalin, New York 2010); A. Paul, Katyń. Stalinowska masakra i tryumf prawdy, Warszawa 2010, pp. 198–211 (Katyn: Stalin’s massacre and the Seeds of Polish Resurrection, New York 1991).

Zbrodnia katyńska w świetle dokumentów (including the foreword by general W. Anders), Londyn 1980, pp. 85 (The Crime of Katyn: Facts and Documents, London 1989); J. K. Zawodny, Death in the Forest. The Story of Katyn Forest Massacre, London 1971, p. 15; J. Mackiewicz, Sprawa mordu katyńskiego. Ta książka była pierwsza, Londyn 2009, pp. 106–108 (Katyn – ungesühntes Verbrechen, Zurich 1949; The Katyn Wood Murders, London 1951).

Zbrodnia katyńska w świetle dokumentów (including the foreword by general W. Anders), Londyn 1980, p. 86 (The Crime of Katyn: Facts and Documents, London 1989); A. Paul, Katyń. Stalinowska masakra i tryumf prawdy, Warszawa 2010, pp. 239–240 (Katyn: Stalin’s massacre and the Seeds of Polish Resurrection, New York 1991); J. Mackiewicz, Sprawa mordu katyńskiego. Ta książka była pierwsza, Londyn 2009, pp. 109–111 (Katyn – ungesühntes Verbrechen, Zurich 1949; The Katyn Wood Murders, London 1951).

W. Materski, Katyń. Od kłamstwa ku prawdzie, Warszawa 2012, pp. 81–88.

Armia Krajowa w dokumentach 1939–1945, T. Pełczyński ed. et al., vol. 2: Czerwiec 1941– kwiecień 1943, Wrocław 1990, pp. 505–509; Zbrodnia katyńska w świetle dokumentów (including the foreword by general W. Anders), Londyn 1980, p. 94 (The Crime of Katyn: Facts and Documents, London 1989); A. Paul, Katyń. Stalinowska masakra i tryumf prawdy, Warszawa 2010, pp. 245–250 (Katyn: Stalin’s massacre and the Seeds of Polish Resurrection, New York 1991).

J. K. Zawodny, Death in the Forest. The Story of Katyn Forest Massacre, London 1971, pp. 16–17; A. Przewoźnik, J. Adamska, Katyń. Zbrodnia. Prawda. Pamięć, Warszawa 2010, pp. 290–293.

J. Mackiewicz, Sprawa mordu katyńskiego. Ta książka była pierwsza, Londyn 2009, pp. 147–171 (Katyn – ungesühntes Verbrechen, Zurich 1949; The Katyn Wood Murders, London 1951); J. Czapski, Prawda o Katyniu, in: Na nieludzkiej ziemi, Kraków 2011, pp. 370–372; F. Goetel, Czasy wojny, Gdańsk 1990, pp. 104–105; J. K. Zawodny, Death in the Forest. The Story of Katyn Forest Massacre, London 1971, pp. 17–25; A. Paul, Katyń. Stalinowska masakra i tryumf prawdy, Warszawa 2010, pp. 231–237 (Katyn: Stalin’s massacre and the Seeds of Polish Resurrection, New York 1991).

More in: A. Spiess, H. Lichtenstein, Akcja „Tannenberg“. Pretekst do rozpętania II wojny światowej, Warszawa 1990 (Unternehmen Tannenberg 1979) and J. Böhler, K. M. Mallmann, J. Matthäus: Einsatzgruppen w Polsce, Warszawa 2009.

The description of the whole action is fully presented in the following paper: M. Wardzyńska, Był rok 1939 Operacja niemieckiej policji bezpieczeństwa w Polsce. Intelligenzaktion, Warszawa 2009.

More in: Podstępne uwięzienie profesorów Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego i Akademii Górniczej (6 XI 1939 r.). Dokumenty, comp. J. Buszko, I. Paczyńska, Kraków 1995; J. August, Sonderaktion Krakau. Die Verhaftung der Krakauer Wissenschaftler am 6. November 1939, Hamburg 1997; A. K. Banach, J. Dybiec, K. Stopka, The History of Jagiellonian University, Kraków 2000, pp. 193–195.

Ausserordentliche Befriedungsaktion 1940. Akcja AB na ziemiach polskich, (the materials from the symposium (6–7 November 1986 r.). the introd. Z. Mańkowski, ed., Warszawa 1992. (The Introduction by Z. Mańkowski presents the whole action, the articles describe the action in different parts of Poland); Zagłada polskich elit. Akcja AB – Katyń, A. Piekarska, ed., Warszawa 2009, (katalog wystawy) also available at www.pamiec.pl/portal/pa/1506/10757/Zaglada_polskich_elit_ Akcja_AB__Katyn.html

L. R. Coatney, The Katyn Masacre: An Assessment of its Significance as a Public and Historical Issue in the United States and Great Britain, 1993, p. 19.

Katyn. A Crime Without Punishment, A. M. Cienciala, N. Lebedeva, W. Materski, eds., New Haven 2007, pp. 215–222, 305–310.

P. Łysakowski, Kłamstwo katyńskie, Biuletyn Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej, no. 5–6, 2005, pp. 87–88; J. Zawodny, Death in the Forest. The Story of Katyn Forest Massacre, New York 1988, p. 38; A. Paul, Katyń. Stalinowska masakra i tryumf prawdy, Warszawa 2003, p. 216 (Katyn: Stalin’s massacre and the Seeds of Polish Resurrection, New York 1991).

W. Wasilewski, Kłamstwo katyńskie – narodziny i trwanie, in: Zbrodnia Katyńska. W kręgu prawdy i kłamstwa, S. Kalbarczyk, ed., Warszawa 2010, pp. 69–83; Katyn. A Crime Without Punishment, A. M. Cienciala, N. Lebedeva, W. Materski, eds., New Haven 2007, pp. 226–229, 319–326.

W. Wasilewski, Kłamstwo katyńskie – narodziny i trwanie, in: Zbrodnia Katyńska. W kręgu prawdy i kłamstwa, S. Kalbarczyk, ed., Warszawa 2010, p. 84; Katyn. A Crime Without Punishment, A. M. Cienciala, N. Lebedeva, W. Materski, eds. New Haven 2007, pp. 222–226, 233–234; R. Kotarba, Śledztwo czy mistyfikacja?, in: Stanisław M. Jankowski, R. Kotarba, Literaci a sprawa katyńska – 1945, Kraków 2003, pp. 81–132; J. Zawodny, Death in the Forest. The Story of Katyn Forest Massacre, New York 1988, p. 172.

D. Gabrel, Historia postępowań w sprawie Zbrodni Katyńskiej, in: Zbrodnia Katyńska. W kręgu prawdy i kłamstwa, S. Kalbarczyk, ed., Warszawa 2010, pp. 23–24; Katyn. A Crime Without Punishment, A. M. Cienciala, N. Lebedeva, W. Materski, eds., New Haven 2007, pp. 228– 235, 326–330; J. Zawodny, Death in the Forest. The Story of Katyn Forest Massacre, New York 1988, pp. 59–76.

S. Kalbarczyk, Zbrodnia Katyńska po 70 latach: krótki przegląd ustaleń historiografii, in: Zbrodnia Katyńska. W kręgu prawdy i kłamstwa, S. Kalbarczyk, ed., Warszawa 2010, p. 20; Katyn. A Crime Without Punishment, A. M. Cienciala, N. Lebedeva, W. Materski, eds., New Haven 2007, pp. 240–241, 332–334.

W. Wasilewski, Kongres USA wobec Zbrodni Katyńskiej (1951–1952), in: Zbrodnia Katyńska. W kręgu prawdy i kłamstwa, S. Kalbarczyk, ed., Warszawa 2010, pp. 89–108; Katyn. A Crime Without Punishment, A. M. Cienciala, N. Lebedeva, W. Materski, eds., New Haven 2007, pp. 235–239, 330.

Dokumenty dotyczące Zbrodni Katyńskiej przekazane do IPN przez Służbę Bezpieczeństwa Ukrainy, in: Zbrodnia Katyńska. W kręgu prawdy i kłamstwa, S. Kalbarczyk, ed., Warszawa 2010, pp. 231–236.

Katyn. A Crime Without Punishment, A. M. Cienciala, N. Lebedeva, W. Materski, eds., New Haven 2007, p. 241.

W. Wasilewski, Kłamstwo katyńskie – narodziny i trwanie, in: Zbrodnia Katyńska. W kręgu prawdy i kłamstwa, S. Kalbarczyk, ed., Warszawa 2010, pp. 85–87; P. Gasztold-Seń, Siła przewciw prawdzie. Represje aparatu bezpieczeństwa PRL wobec osób kwestionujących oficjalną wersję Zbrodni Katyńskiej, in: Zbrodnia Katyńska. W kręgu prawdy i kłamstwa, S. Kalbarczyk, ed., Warszawa 2010, pp. 132–153; P. Łysakowski, Kłamstwo katyńskie, Biuletyn Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej, no. 5–6, 2005, pp. 89–93; Katyn. A Crime Without Punishment, A. M. Cienciala, N. Lebedeva, W. Materski, eds., New Haven 2007, pp. 239–245; 334–337.

N. S. Lebiediewa, 60 lat fałszowania i zatajania historii Zbrodni Katyńskiej, „Zeszyty Katyńskie” no. 12, Warszawa 2000, p. 121; P. Łysakowski, Kłamstwo katyńskie, Biuletyn Instytu-tu Pamięci Narodowej, no. 5–6, 2005, p. 94; www.wiadomosci.gazeta.pl/wiadomosci/1,11488 1,4958005.html (Accessed 03.04.2013).

S. Swianiewicz, W cieniu Katynia, Paryż 1976. (S. Swianiewicz, In the Shadow of Katyn: Stalin’s terror, Pender Island 2002).

J. Czapski, Wspomnienia starobielskie 2011 (J. Czapski, Souvenirs de Starobielsk, Paris 1987; J. Czapski, Ricordi di Starobielsk, Roma 1945.

J. Czapski, Na nieludzkiej ziemi, Instytut Literacki 1969 (J. Czapski, The Inhuman Land, Londyn 1987; J. Czapski, La terre inhumaine. Adapté du pol., Lausanne 1979; J. Czapski, Unmenschliche Erde Frankfurt a.M 1969).

Instytut Katyński, in: Wspomnienia Adama Macedońskiego, założyciela KPN, www.bibula. com/?p=8571; Pierwsze nadanie Medalu Dnia Pamięci Ofiar Zbrodni Katyńskiej 8 kwietnia 2008 r., „Zeszyty Katyńskie” (2008), no. 24, pp. 253–255.

A. Kostrzewski, Stanisław M. Jankowski, Biuletyn Katyński, „Zeszyty Katyńskie” (1995), no. 5, pp. 150–155.

A. Macedoński, Historia Instytutu Katyńskiego w Polsce, „Zeszyty Katyńskie” (1996), no. 6, Warszawa 1996, pp. 188–192.

P. Niedzielak, Ostatnia ofiara Katynia: w świetle faktów i dokumentów, Warszawa 1991; P. Litka, Katyński kurier, „Tygodnik Powszechny”, 18 I 2009.

Śmierć przy studzience, comp. S. M. Jankowski, „Biuletyn Katyński” (1991), no. 1, p. 8–17.

M. Lewandowski, M. Gawlikowski, Prześladowani, wyszydzani, zapomniani... Niepokonani, Vol. I. ROPCiO i KPN w Krakowie 1977–1981, Kraków 2009; M. Majewski, Badylak. Żywa pochodnia rozświetlająca prawdę o Katyniu, www.fronda.pl/a/badylak-zywa-pochodnia-rozswietlajaca-prawde-o-katyniu,5746.html?page=2&.

D. Gabrel, Historia postępowań w sprawie Zbrodni Katyńskiej, in: Zbrodnia Katyńska. W kręgu prawdy i kłamstwa, S. Kalbarczyk, ed., Warszawa 2010, pp. 24–27; A. Przewoźnik, J. Adamska, Katyń. Zbrodnia. Prawda. Pamięć, Warszawa 2010, p. 440.

A. Przewoźnik, J. Adamska, Katyń. Zbrodnia. Prawda. Pamięć, Warszawa 2010, pp. 449– 453; Katyn. A Crime Without Punishment, A. M. Cienciala, N. Lebedeva, W. Materski, eds., New Haven 2007, pp. 251–257, 344–348.

D. Gabrel, Historia postępowań w sprawie Zbrodni Katyńskiej, in: Zbrodnia Katyńska. W kręgu prawdy i kłamstwa, S. Kalbarczyk, ed., Warszawa 2010, pp., 40–41; Polish researchers, law theorists and public prosecutors deny this statement, refer to, among others, to articles in: Zbrodnia Katyńska. W kręgu prawdy i kłamstwa, S. Kalbarczyk, ed., Warszawa 2010: M. Kuźniar-Plota, Kwalifikacja prawna Zbrodni Katyńskiej – wybrane zagadnienia, pp. 42–51; W. Kulesza, Zbrodnia Katyńska jako akt ludobójstwa (geneza pojęcia), pp. 52–67; I. C. Kamiński, „Skargi katyńskie” przed Europejskim Trybunałem Praw Człowieka w Strasburgu, pp. 154–170.

I. C. Kamiński, „Skargi katyńskie” przed Europejskim Trybunałem Praw Człowieka w Strasburgu, in: Zbrodnia Katyńska. W kręgu prawdy i kłamstwa, S. Kalbarczyk, ed., Warszawa 2010, pp. 154–170; Historical situations” in the case law of the European Court of Human Rights in Strasburg, “Polish Yearbook of International Law” (2011), vol. XXX, pp. 9–60; Answers to the questions for the hearing in the case of Janowiec and Others v. Russia (joint cases nos. 55508/07 and 29520/09), Strasbourg, 6 October 2011, „Polish Yearbook of Inter-national Law” (2012), vol. XXXI, pp. 409–446.

The record of the sentence of 16.04.2012 in English: www.bi.gazeta.pl/im/6/11547/ m11547036,WYROK.pdf (03.04.2013); Wyrok Europejskiego Trybunału Praw Człowieka w Strasburgu w sprawie „skargi katyńskiej” – właściwość czasowa (ratione temporis) w sprawach dotyczących prawa do życia (Judgment of the European Court of Human Rights in the case of “Katyn complaint” – the Court’s temporal competence in cases concerning the right to life), in: Fides et bellum. The book written in remembrance of Bishop Professor General the late Tadeusz Ploski, Olsztyn 2013, pp. 81–104; www.rp.pl/artykul/942368-Katyn-zima-znow-w-Strasburgu.html (03.04.2013); www.wpolityce.pl/wydarzenia/26725-trybunal-praw-czlowieka-oglosil-wyrok-ws-katynia-rosja-dopuscila-sie-ponizajacego-traktowania-krewnych-ofiar-zbrodni-katynskiej (03.04.2013).

D. Gabrel, Historia postępowań w sprawie Zbrodni Katyńskiej, in: Zbrodnia Katyńska. W kręgu prawdy i kłamstwa, S. Kalbarczyk, ed., Warszawa 2010, pp. 34–35; M. Kuźniar-Plota, Kwalifikacja prawna Zbrodni Katyńskiej – wybrane zagadnienia, p. 42; Katyn. A Crime Without Punishment, A. M. Cienciala, N., Lebedeva, W. Materski, eds., New Haven 2007, p. 264.

D. Gabrel, Historia postępowań w sprawie Zbrodni Katyńskiej, in: Zbrodnia Katyńska.W kręgu prawdy i kłamstwa, S. Kalbarczyk, ed., Warszawa 2010, pp. 35–36; Informacja o działalności Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej – Komisji Ścigania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu w okresie 1 stycznia 2012 r. – 31 grudnia 2012 r., Warszawa 2013, p. 146.

Authors:

Monika Komaniecka, Institute of National Remembrance, Cracow,Poland

Krystyna Samsonowska, Jagiellonian University, Cracow, Poland

Mateusz Szpytma, Institute of National Remembrance, Cracow, Poland

Anna Zechenter Institute of National Remembrance, Cracow, Poland

Source: The Person and the Challenges, Volume 3 (2013) Number 2, p. 65–92

See also: https://ipn.gov.pl/en/news/1105,Katyn-Massacre-Basic-Facts.html