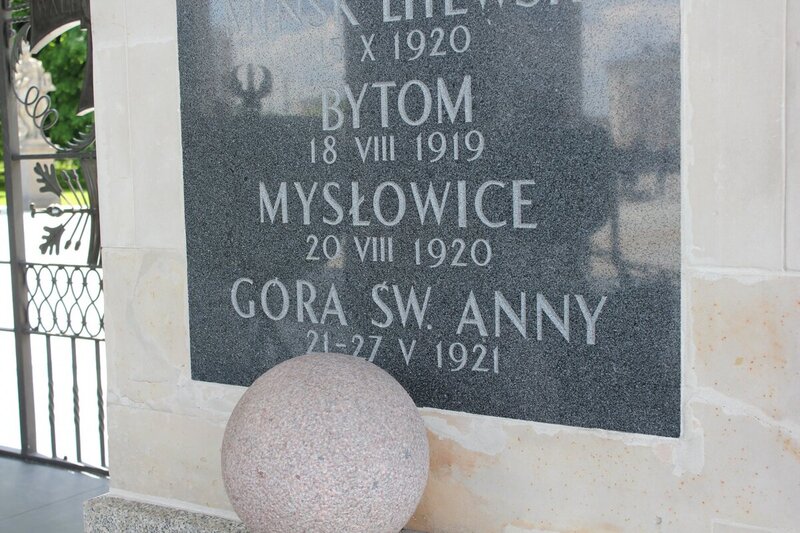

The outbreak of third uprising took the German side completely by surprise. The insurgents quickly captured the industrial area, with the exception of the cities to which access was forbidden by the Coalition. Their blockade began, and the main forces moved westwards, towards the Korfanty Line, i.e. the border of the area the dictator intended to occupy. On 8 May, the strategically important Sankt Annaberg (Góra Świętej Anny) fell into their hands right away.

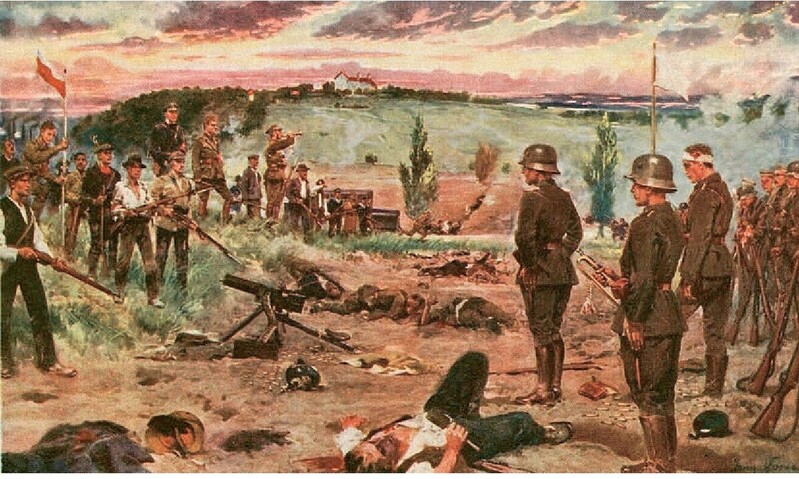

After the Germans recovered, they launched a counter-offensive on 21 May, trying to drive the insurgents out of the area, which they eventually succeeded in doing. Bloody clashes, such as those at Lichinia (Lichynia), cost them about 500 dead, but brought them success. Despite counter-attacks, they did not give up the hill. The nature of the fighting was ruthless; prisoners were not taken; quarter was not given. There were cruel executions (example of Kalinow [Kalinów] and the murdered prisoners of the Mikultschütz [Mikulczyce] company). The battle became one of the symbols of bravery for both sides and was later mythologised, as evidenced by the mausoleums erected there by Germans and then by Poles.

Equally fierce battles took place in nearby Kandrzin (Kędzierzyn). They broke out on the night of 2 May. After the initial success, which was the seizure of the railway station, the insurgents were forced out of it by German APo (Plebiscite Police) officers under the command of Briton A. Craster. On 9 May insurgents again attacked Kandrzin (Kędzierzyn), defended by Lt. Hans von Matuschka. They managed to capture a strategically important railway station.

This was a great success and a serious threat to the southern flank of von Hülsen’s German forces. Armoured trains played an important role in the battle for Kandrzin (Kędzierzyn). As Lt. Włodzimierz Abłamowicz recalled, on the night of 8 May, they broke through from Krakow, and having reached Kandrzin (Kędzierzyn), they carried out a surprise attack on a German armoured train defending the station. To help them, an infantry battalion squadron with trains no. 1 and 7 (240 men, 4 field guns) was brought from Frankenstein in Schlesien (Ząbkowice).

After a short, fierce battle we defeated the German armoured train, which, having escaped, only put up resistance in Oppeln (as in Opole), and we captured Kandrzin (Kędzierzyn) in spite of heavy losses in our unit”.

However, Korfanty unexpectedly stopped the military action and began political dealings, which was misunderstood by the insurgents as the end of the uprising. Some retreated to their homes. The troops became disorganised and discipline decreased.

The local distillery fell into the hands of the insurgents, along with weapon and food warehouses. The command postulated draining thousands of litres of spirit into the Oder River, as the situation was very bad. Drunken soldiers plundered the town. Eventually, most of the spirit was evacuated to the industrial area. The functioning of the local insurgent military police also left much to be desired, having not only failed to prevent pathological behaviour, but participated in it themselves, including the commander. At the first contact with the enemy, they fled. The Germans, on the other hand, gained time to rest and prepare retaliatory measures. The counter-offensive of the third decade of May led to the collapse of the front. To save the situation, on 23 May the garrison of Kandrzin (Kędzierzyn) set off to the front, leaving the city practically defenceless.

In this situation, during the second German counter-offensive in June, the fighting for Kandrzin (Kędzierzyn) began again. The front was broken near Zalesie. However, the German attack from the direction of Klodnitz (Kłodnica) was stopped, and the insurgents, taking advantage of the enemy’s mistakes and supporting themselves with an armoured train, managed to break out of the encirclement threatening them. It should be mentioned that during the retreat from Kandrzin (Kędzierzyn), in contrast to the locals, a few units of the Brieg (Zabrze) military police under Lt. Nowakowski proved themselves. Well equipped, they set an example of determination and commitment, thanks to which the retreat took place in a relatively orderly manner. There was no uncontrolled escape, so the front was maintained. However, this allowed the Bavarians (Freikorps Oberland took part in the fighting) to regain the railway station and Kandrzin (Kędzierzyn), which was an important success. Polish counter-attacks, supported by an armoured train, and attempts to push the Germans out of Kandrzin (Kędzierzyn) ended in failure. Also another attack conducted on 5 June, supported by 3 armoured trains, was repulsed by Freikorps Heydebreck, after whom the town was later renamed. An attempt to recapture the city made on the following day also failed.

The Polish losses in the battle for Kandrzin (Kędzierzyn) are estimated at 700 dead, while the Germans lost twice as many men. It was the bloodiest battle of the Third Uprising. As a result, the front was moved several dozen kilometres to the east. The Germans saw the prospect of seizing Gleiwitz (Gliwice), the gateway to the industrial district, full of Selbstschutz fighters who had taken refuge there from the insurgents. The capture of the city would be the beginning of the end of the uprising.