We often do not realise that the construction of moral capital, and therefore the use of history as soft-power in international relations, still takes place as far as WWII is concerned. It seems that three key areas can be identified here: support for Nazism, support/co-operation in the Holocaust, and the role in defeating Nazism. They determine the specific positioning of nations and states in the hierarchy of historical diplomacy. It is essential not only to present oneself in such a light as is favourable from the particular state power’s point of view but also to attempt to impose a narrative about other actors in international relations. That requires initiatives that may change the perception of other nations or states, which would facilitate diplomatic pressure and the pursuit of own interests, no longer historical, but contemporary ones.

Poles in the years of World War II

It is from such a perspective that I would be inclined to perceive the attempts – sometimes coordinated, sometimes chaotic – to move Poles from the group of WWII victim nations to those that are co-responsible for the war crimes against Jews.These actions arouse understandably strong emotions in our society. Historically, there is no doubt that we were – as a national community – not only the first victim of the German and later Soviet aggression of September 1939 but also the first nation to offer armed resistance to aggressive totalitarian regimes. Similarly, there is no doubt that we were one of the states most affected by the WWII tragedy.

It is estimated that more than 5.5 million Polish citizens perished in the war (these figures are very rough), including nearly 3 million Jews. Before the war, 35 million people lived in the Second Polish Republic, while there were only 24 million in the territory of post-Yalta Poland. It reflects not only the death toll but also population loss resulting from the Soviets taking over almost half of Poland’s pre-war territory, as well as from vast number of our compatriots remaining in the West, in the free world countries, after the war.

That said, we cannot forget the material losses caused by the frontline going back and forth across our lands, or the plunder by both occupants – the latter including confiscation of private property. Then, there was both occupants taking advantage of the economic potential of the occupied Polish lands, and exploitation of the citizens as slave labourers. While thinking about the economy, the destruction of the infrastructure (not only buildings or transport routes but sometimes the entire cities, like Warsaw after the Uprising), or the pillage policy of the occupants, we must not overlook the damage to science and culture. It included the destruction of historical objects and theft of works of art or book collections, archival records, etc., and their transfer out of Poland. The problem is a complex one, and, as a matter of fact, in this text, only touching Polish losses resulting from the actions of the German Third Reich and the Soviet Union, it has been barely discussed. Yet, other fundamental issues should be mentioned here, however intangible.

Poland, as the formal victor – the only of the anti-Hitler allies which fought against totalitarian regimes from September 1939 to the last day of the war – did not regain independence and was dominated by the Soviets. The scope of that generation’s tragedy is visible in the destruction by the Red Army, the Smersh and the NKVD of one of the most remarkable phenomena in the history of WWII, namely the Polish Underground State, as well as the underground Polish troops, the Home Army. The Western approval for Moscow's forcible breakup – murder or enslavement – of the Polish civil and military authorities subordinated to the constitutional government of the Republic of Poland in exile reveals the anatomy of geopolitics. At the same time, it makes you understand why certain circles in the Western societies keep supporting the myth of the 'liberation' of a part of Europe by the Soviets, contrary to the obvious facts. The Red Army conquered Central and Eastern Europe, enslaved the peoples living there – who before the war generally enjoyed freedom and national sovereignty – and subjected their elites, striving to regain independence, to brutal repression. It also seized their lands, such as the Polish Kresy (Borderlands), a significant part of the pre-war Second Polish Republic territory. All this happened with the tacit approval of the Western world.

The history of Poland in the years 1939-1945 is a story of the strength of spirit, steadfastness and determination that enabled the creation of underground state structures (including an underground army), as well as armed forces loyally fighting not only for their country’s freedom but also the freedom of other nations of Western Europe. This is what happened in France, Great Britain, Norway, Italy, Holland and many other places where soldiers of the Polish Armed Forces in the West shed their blood – not for Warsaw, but for Paris, Narvik, London, Arnhem or Ancona...

Between history and its falsification

That is why we are disturbed by the attempts at evident falsification of our history or extracting individual phenomena from this context and elevating them to the rank of a general principle.

One of the aspects of the problem is the historical lies symbolically conveyed in the phrase "Polish concentration camps", often conscious and intentional falsification of the WWII history through language that attributes the guilt of German crimes to Poles.

Another one – much more significant because complex – is related to the assessment of the Polish society and its attitude to the Jewish population during the occupation. The nature of this dispute is truly bipolar. On the one hand, some opinions attribute Poles the complicity in the Holocaust by emphasising the shameful cases of handing the Jewish population over to the occupant or blackmail, i.e. extorting money or valuables from Jews with threats of denunciation – or, sheltering Jews as a means of personal enrichment at their expense. On the other hand, there is a view that overlooks or downplays the problem of wrong behaviour on the part of the Polish population, and emphasises the praiseworthy cases of Poles looking after and hiding Jews.

The issue of Polish-Jewish relations under German occupation is one of the most challenging research problems, made up of a multidimensional and complicated network of historical connections and processes. Focusing only on selected few gives us an incomplete picture, and distorts the historical perspective. Simultaneously, it is difficult not to notice many emotions in this sphere of research and, perhaps above all, in journalism. Moreover, the politicization of some threads of the historical dispute is also not without significance as it has become a convenient tool for achieving various goals in the international and domestic arena.

The context of state activity is crucial and often overlooked. The Underground Republic of Poland established the Council for Aid to Jews "Żegota", which, acting under the auspices of the Government Delegation for Poland, was the only initiative of its kind in occupied Europe. We also forget that it was Poles who told the world about German crimes against Jews, and demanding that the world react. In December 1942, the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Polish Government in Exile presented the Western Allies with a report on the Holocaust, which was then forwarded as an official note to the signatory countries of the United Nations Declaration.

The issue of the Polish state activities, operating underground in harsh conditions of the occupation, is one of the examples of Polish attitudes towards Jews (most often pre-war Polish citizens) during WWII. Others reflect the Polish society's attitudes, stretching between the opposite poles of criminal collaboration with the German occupier, and altruistic, heroic aid provided to Jews condemned by the Germans to the Holocaust – the aid, we must remember, that from 1941 carried the risk of death not only to the helper but also to their household. It means that the helpers forfeited their own life, but also the lives of their spouse, children or parents. And all this took place in the broader context of German repressions in the occupied territories.

Therefore, if we take out and analyse single elements from this extraordinarily complex and multidimensional wartime reality, the resulting conclusions will be impaired since they will not reflect the multifaceted nature of the situation. It applies equally to the research that focuses exclusively on the Holocaust and studies of the aid to Jews; both need to be put in the context of the German policy of terror against the population of the occupied territories.

Remembrance of World War II

Another important phenomenon is the unbalanced evaluation of German and Soviet totalitarian regimes, though the problem is much broader: it refers not only to WWII but to the assessment of Nazism and communism in general, in which criminal nature of the latter is frequently downplayed. Collaboration with the German Third Reich is commonly seen as something embarrassing and ruining the moral capital of these communities that collaborated with Nazism. However, the collaboration with Moscow no longer receives such critical assessment. It has many sources, but to some extent, it is the result of communist totalitarianism in the anti-Hitler coalition. The free world's military alliance with the Soviets required Western societies to become "familiar" with them. From a historical perspective, the fact that one totalitarian regime defeated another does not change the victor's nature, essence, and aims. The Soviets were an aggressive totalitarian state, from 1917 onwards seeking to control as much of Europe as possible. Nothing changed in their aspirations either in 1919, when the Red Army (fortunately halted by the Poles near Warsaw in 1920) was moving westwards to carry the flame of communist revolution, or in 1939, when, with the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact concluded with Germany, both totalitarian states divided Europe between themselves, or in 1943, when, after the Battle of Stalingrad, the Red Army again moved westwards. It moved to defeat Hitler and simultaneously enslave Central and Eastern Europe and impose communism on it.

We experienced Bolshevik and later Soviet aggression in a unique way. Most nations conquered by the Soviets at the end of the war and dominated by Moscow between 1945 and 1989 did not experience the 1917-1939 Bolshevik crimes. We are the ones who remember the Polish-Bolshevik war or the so-called NKVD Polish operation of 1937-1938, and later the first occupation and the 1940 Katyń Massacre. Ukrainians have the trauma of the Great Famine encoded in their social consciousness. The Baltic states, which emerged after the First World War, only experienced the communist crimes of the Second War, when the Soviets stripped them of their newly won or regained sovereignty, and most of the countries of Central and Eastern Europe were free from the clash with criminal communism until the front lines were crossed in 1944-1945. That is one reason why awareness of the Soviet imperial aspirations of 1917-1939 is almost non-existent in Western societies.

Seeing the struggles relating to the memory of World War II and its falsification, we should consistently recall our history, all the more so because the Second World War is important not only in historical diplomacy but also in our popular belief. In 2004 CBOS asked 'What is World War II for you personally', and as many as 73% of respondents indicated that it was 'still a living part of Polish history, which should be constantly reminded'. After fifteen years, the ratio has increased: in 2019, already 82% responded like that. Importantly, this level of belief is high regardless of our political views.

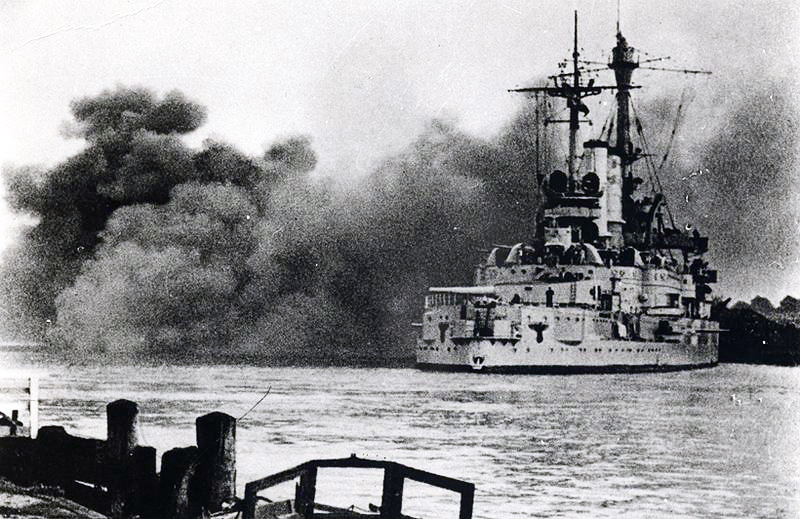

1 September and 17 September 1939 changed the history of the world - the aggressions of the German Third Reich and the Soviet Union against Poland, which started World War II, caused totalitarian ideologies to take over most of Europe for many years, and the post-war division between communist states and the states of the free world dominated the geopolitical balance of power for almost half a century.

The anniversary of the outbreak of World War II is also an occasion to draw attention to the martyrdom of the Polish nation. After all, in another CBOS survey, the most significant number of respondents - 14% - indicated World War II and the German occupation as 'Poland's greatest failure in the last hundred years'. Another matter is that the respondents spoke only about the German occupation, although in 1939-1941, half of the Second Republic was under the Soviet occupation, which indicates significant problems connected with our historical awareness.

What is fundamental, however, is that we are a nation not closed in by the trauma of war, but proud of our ancestors’ attitude in the years of great trial. Above all, we are proud of the Warsaw Uprising (as 46% of respondents declared in 2019), but also of the organisation of the Polish Underground State and the Home Army (42% responds). Interestingly, our ancestors attitude during September 1939 is also appreciated by 36% of respondents, although these actions ended in defeat and the division of the Second Republic’s territory between the German Third Reich and the Soviet Union. More and more of us also believe that we should be proud of saving Jews during the war; in 2014, 26% of respondents thought so, and in 2019, it was already 30%.

Nowadays, in connection with attempts to cover up the history of World War II, recalling those events from years ago is of crucial importance. The absurdity of the propaganda activities of some circles - given, for example, the next anniversary of the attack on Poland by the German Third Reich and later by the Soviet Union - seems obvious. Yet, due to contemporary political interests, the lies persist. We should not ignore them, because contrary to popular belief, the truth will not defend itself.

By Filip Musiał, Ph.D., D.Sc.