It may seem that Upper Silesia, located on the Polish-German border, would be an area of interest only to those two countries. In the meantime, it turned out that although some politicians in Paris and London could not even point to the region on a map, it had become part of a greater international rivalry. Although the Paris Conference (18 January – 28 June 1919) included representatives of 32 so-called Major Allied and Associated Powers as the victors of the Great War, it was the “big four” – US President Thomas Woodrow Wilson, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau, and Italian Prime Minister Vittorio Emanuele Orlando – who decided on matters relating to Europe. During the deliberations, it became clear that achieving unanimity among the victors would be difficult. The establishment of a collective security system, to be symbolised by the League of Nations, initially proposed by T.W. Wilson as a means of maintaining world peace, did not find understanding with the European partners. The British authorities were particularly critical nearly from the start, having for years preferred the concept of a balance of power, which was the idée fixe of the British continental policy. The differences between the superpowers soon meant that instead of the right to self-determination, Realpolitik, based on the calculation of power and national interests, became the guiding principle. At the start of the conference, the position of the main decision-makers on the issue of Upper Silesia were favourable towards Poland. However, protracted talks on the future of the region brought about a change in the situation.

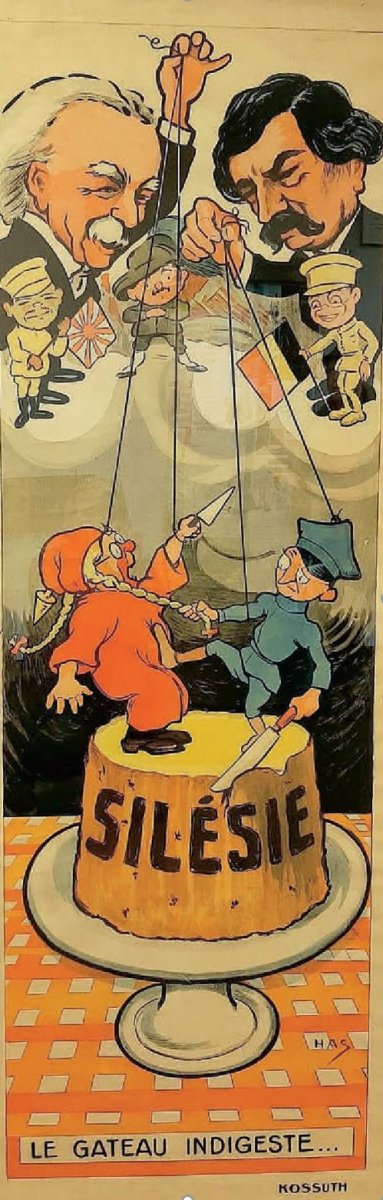

The decision about where Upper Silesia belonged became part of an open and at times quite intense Franco-British conflict.. France supported solutions that were favourable for Poland. As a result, it was described by the German side as Erfeind, “the greatest enemy”, or Erbfeind, “the hereditary enemy” of Germany, who wanted to hand Upper Silesia over to Poland, as the Germans argued, without regard for the will of the population and without considering the role the German state had played in shaping the region in the past two centuries.

The Upper Silesian issue thus became part of the construction of a new European equilibrium, in which the previous allies – Great Britain (supported by Italy) and France – became rivals. Fearing a fast reconstruction of the military and economic power of Germany, the French based their foreign policy on three foundations: a quick and decisive execution of the Treaty of Versailles, the further weakening of Germany, and the strengthening of one of the Central European states. In the latter role, the French government saw Poland, which with their help was to become an important element of the new European order.

However, a strong Poland meant a weak Germany and consequently a strong France, which the British did not want. For them, the objectives of the Great War had been mostly achieved with the destruction of the German high seas fleet and the dismantling of the German colonial empire. All that was needed was to receive substantial reparations. From there, it was only a step to the famous and oft-quoted (although frequently erroneously) statement by D. Lloyd George, made during the Paris Peace Conference that “giving the industry of Silesia to the Poles would be like giving a watch to a monkey”. The British also had a strongly negative view of Polish competence in the field of economy.

Finally, for the leaders of the third of the European powers deciding about the post-war order in Italy, the Upper Silesian issue was of secondary importance, being only one of many elements of the post-war political mosaic. It was only with time that fears of the rise of France’s position brought the Italian politicians closer to the British attitude. At the same time, the passage of time and progressing talks made it clear that the President of the United States increasingly avoided involvement in political activities concerning Europe.

The results of the differences in the vision of Europe’s future first included, among others, the Upper Silesian plebiscite of 20 March 1921 and then the widely divergent concepts for the demarcation of the Polish-German border in the region.

While the organisation of the plebiscite was still a consequence of the principle of national self-determination advocated by T.W. Wilson, subsequent actions were a good illustration of the so-called Realpolitik put into practice by the leaders of the European powers. Consequently, in addition to steps taken directly in Upper Silesia and the diplomatic activities of the Polish and German sides, it is worth noting that the complex “jigsaw puzzle” also consisted of events taking place in other parts of the world, such as the conference held in the Belgian town of Spa in mid-1920, when Germany’s delay in implementing the Treaty of Versailles and its refusal to pay reparations necessitated the need for Britain to support France, or the so-called Greco-Turkish affair of mid-1921, when the French government’s concessions to Great Britain outside Europe brought about a similar British attitude towards France in Europe (including the “Upper Silesia issue”).

The decision of the Council (Conference) of Ambassadors about the division of the region on 20 October 1921 was thus the conclusion to a complicated and lengthy process, lasting over two years, of shaping the influence of the victorious powers. Although the border settlement did not ultimately satisfy any of the rival sides, it was generally perceived as a victory not only for the Poles, but also for the French, especially given that shortly after the Second Republic of Poland took over the so-called Polish Upper Silesia, a large part of the industry there ended up in French hands.