Among the fugitives from the ghettos of the General-Gouvernement, trying to survive the nightmare of the occupation, there were many assimilated people who knew very well Polish culture, customs and Catholic rituals. They associated the chance of survival with adopting a false Polish identity. To survive, however, it was necessary to obtain documents that did not arouse suspicions by the Germans. The most valuable of them was the certificate of the sacrament of baptism, commonly referred to as "baptismal certificate".

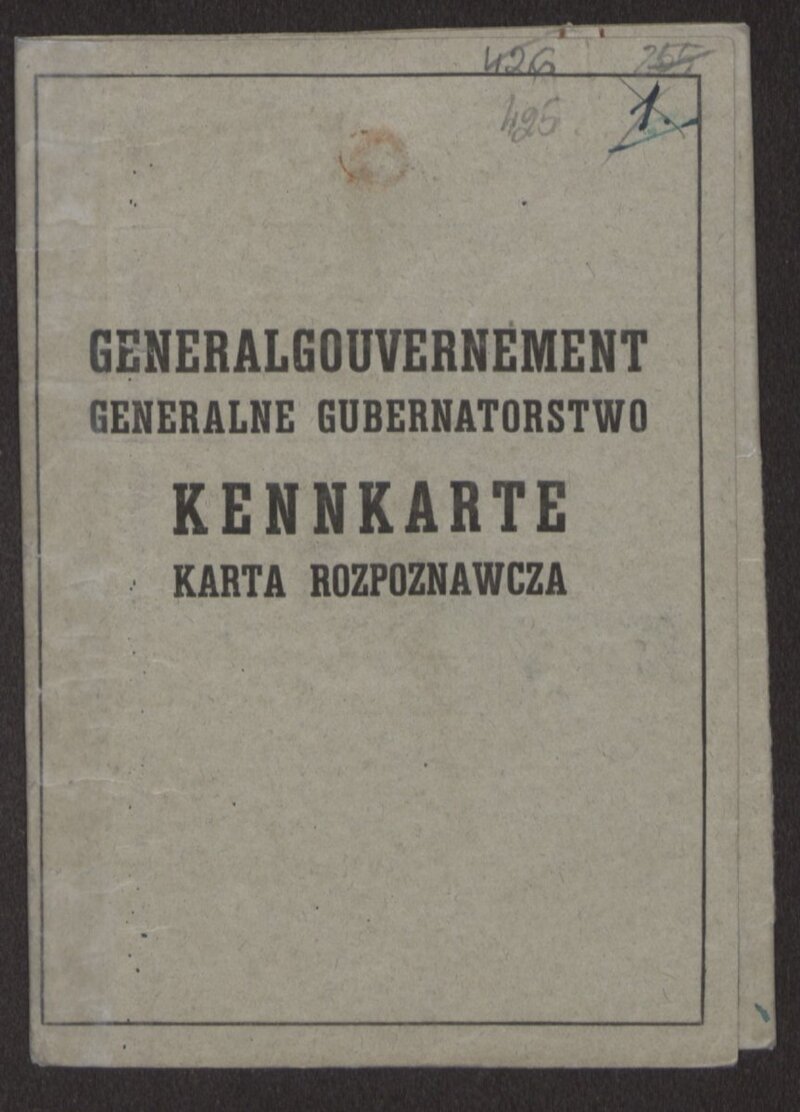

Since 1942, every adult Pole detained by a German patrol in the street, on a train or another place was required to identify himself or herself with an identification card (Kennkarte in German) with a photograph, fingerprints and address of residence as well as an Ausweis, i.e. a certificate of employment. Due to the delay in issuing Kennkartes, especially in small towns and villages - identification with a baptismal certificate and a registration certificate was generally tolerated. The lack of these documents resulted in immediate arrest, which in the case of Jews meant the beginning of a road usually ending with death.

Friends' gestures

For a ghetto escapee, the easiest way to get a baptismal certificate was to ask Polish friends for it. There are numerous traces of such help in post-war reminiscence. And so, the teenage Sala Zylberbaum received a baptismal certificate of "some allegedly dead little girl" from a Polish friend; Stefan Bulaszewski from Warsaw presented Maria Justman with his sister's baptismal certificate; and Shoshana Rakowska from Ruszcza near Cracow received a baptismal certificate from Jan Rzepecki of his female relative, who settled in the Eastern Borderlands. Julian Lewenstein, who lived in Kazimierz by the Vistula River, was offered by the Polish friends the baptismal certificate of Aleksander Kosidło, who had emigrated to the United States before the war; Józef Mützenmacher from Lviv received the baptismal certificate of Jan Kot - a soldier of the Polish Army, who disappeared without a trace in September 1939. A fugitive was informed that the man's parents knew about the mystification and, if necessary, would certify that Jan Kot had returned home. In all these cases, the benefactors did not expect any remuneration for their deeds.

In each case, the recipients were aware that their benefactors risked repressions from the Germans. A little card was priceless, giving a real chance to save one's life. An exhausted and hungry fugitive from a forced labour camp, Michał Chęciński, who admitted to a Pole, Bronisław Słaby, that he was a Jew, related years later: "»I have an idea«- says Bronek with conviction. »When were you born?«. »In 1924«. »Cool«. One Russian left behind his baptismal certificate with me. His name was Mikołaj Sadowski, it is a kind of Polish surname. Only he was born in Odessa in 1905. But the Germans don't know where this Odessa is anyway. I will scratch this zero a bit and it will make 1925. Just right for you. And you will pass for that Mikołaj, do you understand?”. The next day, on the basis of a forged baptismal certificate, Michał Chęciński obtained a certificate of taking up work from the Germans. "I can't believe my eyes how easy it was to grant me the right to exist on this earth," he recollected. "What would I do without you, Bronek?"

Help in parishes

Parish offices were the places where most of the baptismal certificates given to the hiding Jews came from. The discovery by the Germans of a forged baptismal certificate bearing an impress of a real parish seal and the parish priest's signature was punishable by an immediate reaction of Gestapo officers. Despite the constant threat, such help was undertaken by many clergymen. The most remembered person was Fr. Marceli Godlewski, the parish priest of All Saints Parish, which was located within the Warsaw ghetto. But other clergymen also helped the fugitives from the ghettos, e.g. Fr. Stefan Podsiedlik from Miechów or Fr. Ludwik Barski from Ciepielów. Even if the parish priests did not help directly, they often tolerated the illegal activities of their associates and friends. "I went to the parish in Podgórze to the parish priest Józef Niemczyński," recalled one of the witnesses. - He knew me from a very young age; I was walking around the parish, and when the church man turned his back, I used to steal record forms, put impressions of seals and a facsimile of the parish priest. The second priest, Stanisław Mazak, filled these forms up in Latin".

In the largest parishes, not only priests but also secretaries, and in some cases also members of their families, were involved in issuing extracts from parish registers. Stanisław Szymański, a citizen of Warsaw, recalled that, having general information about the person whose documents had to be obtained, he contacted Feliksa Piotrowska - the wife of the organist of the Church of Visitation of the Blessed Virgin Mary in the Old Town. She searched the files for data of deceased people that matched the "needs", and then prepared their baptismal certificates.

In turn, Bronisław Nietyksza recollected years later: "I was in contact with two Roman Catholic parishes - one in Three Crosses Square (St. Alexander) and the other in Narutowicza Square (St. James). I had an agreement with the parish priests and secretaries of these parishes not to issue death certificates to the deceased persons aged 18-60, leaving them in the files as persons still living in the parish. If it was necessary to issue a Kennkarte to a person of Jewish origin as an Aryan, then there was selected an appropriate certificate of birth of a person who was already deceased, but not removed from the records of the living. In this way, these people obtained authentic and formally genuine documents".

Instead of an end

For some people, being given the chance to go on with life was a miracle, coupled with experiences beyond rational reasoning. The memories of the teenage Jakub Michlewicz, who after escaping from the Warsaw ghetto, was hiding in a village near Piaseczno, pretending to be a Pole, sound very special. He recollected: "After some time the host told me to go get my baptismal certificate. I went to Warsaw twice to my Polish friends, [but] they refused to give me a baptismal certificate. The third time, the host said: »You have to bring a baptismal certificate, and I will keep you, even if you are a Jew, but if you don't have a baptismal certificate, don't come back to me at all«. I couldn't sleep because of worry, and when I fell asleep, I dreamed about Mummy and she told me to go to one boy with whom we used to live together, and he will give me a baptismal certificate. I went and this boy bought a baptismal certificate and gave it to me. I returned to the host with the baptismal certificate. There was also a problem, because they called me Jasiu, and it was Ryszard that was written in the certificate. But I said it was my mother who called me that."

The name of the teenage Ryszard, who decided to help his Jewish friend, will probably remain unknown forever. The same is true of many people who, at the moment of their greatest ordeal, decided to help their neighbours.

SEBASTIAN PIĄTKOWSKI, PhD, DSc.