The allegation of participation in the partition of Czechoslovakia in the fall of 1938 is one of the permanent elements of the historical narrative directed against Poland. The decision on partition of the territory of the First Republic was made on September 29 during a conference in Munich with the participation of France, Germany, Great Britain and Italy. The democratic Western powers took a passive stance, agreeing to implement Hitler's demands. The final course of the new borders was to be decided by a special commission composed of representatives of the parties contracting in the capital of Bavaria and the ČSR. The conference participants also issued an additional statement to the concluded agreement, which concerned the Polish and Hungarian minorities in Czechoslovakia. In the absence of a compromise on these issues, it was announced that the Munich Four would meet again after three months.

Polish diplomacy presented its position on the decisions taken after they were made public, stressing that it did not recognize them as binding and was consistently based on the principle of "nothing about us without us". In Warsaw, it was feared that the powers would come to an understanding with Germany at the expense of the Polish Republic, as in the case of the ČSR, making it the object of a diplomatic game. In the political situation prevailing in Europe at that time, there was a real threat of applying "Munich methods" in relation to Gdańsk, Polish Pomerania or Silesia.

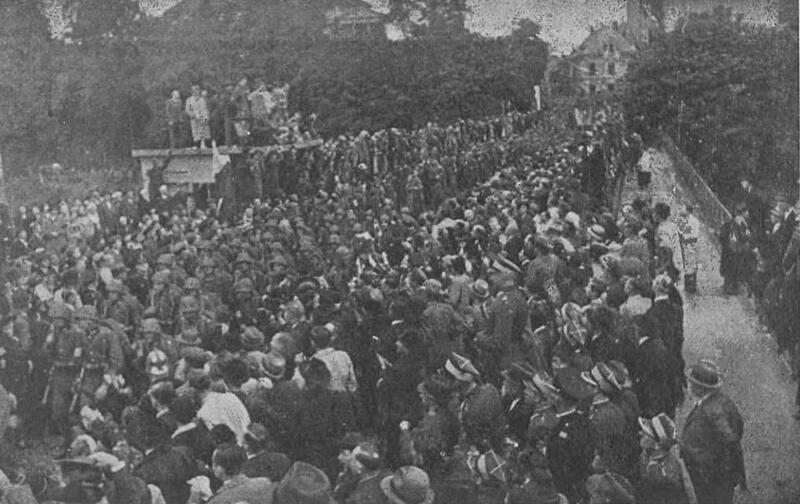

For this reason, on September 30, 1938, Poland issued an ultimatum to Prague, expecting the constituencies of Cieszyn and Fryštát to be included within the borders of the Republic of Poland within ten days, conducting a plebiscite in the remaining territories of the Republic inhabited by Poles, and the release of all political prisoners of Polish origin. On October 1, the demands were accepted and the ČSR authorities emphasized their goodwill in efforts to resolve the conflict.

Considerations about the possible appearance of Poland in defence of the ČSR are purely speculative. There is no doubt that the passivity of the great powers and the willingness to shift political and moral responsibility for the course of events to the Republic of Poland determined the actions of the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and ruled out the possibility of Poland acting in defence of its southern neighbour. In the international situation of that time, such an action was doomed to failure, and the Polish Republic would fight alone with the Third Reich due to Paris and London's unpreparedness for war and their adherence to the appeasement policy. On the other hand, the view that in the event of an armed conflict with Germany the Polish army would actively support France, if only it showed the will to fulfil its alliance obligations towards Prague, is fully justified. Thus, the responsibility for the crisis of Czechoslovak statehood rests with France and Great Britain, whose diplomatic representatives repeatedly forced Prague to make subsequent concessions to Berlin in 1938.

The Republic of Poland did not initiate actions aimed at the territorial disintegration of the state of Czechs and Slovaks. Also, the Polish minority, living in a dense mass at the Polish-Czechoslovak borderland (mainly Cieszyn Silesia), subjected to harassment for years, was not the main driving force causing further crises of the Czechoslovak statehood. The Poles living in the Republic modelled their postulates on the programme of other minorities, so they certainly were not a factor analogous to the role played by the Sudeten Germans.

The Poland's relations with the state of the Czechs and Slovaks cannot be considered without taking into account the role of Germany in Europe. Historians today reject the thesis about the existence of a secret Polish-German agreement on Czechoslovakia, often raised in the historiography of the People's Republic of Poland, following the propaganda interpretation of history created by Soviet researchers. The entry of Polish troops into Zaolzie should be interpreted as an anti-German step, aimed not only at emphasizing Poland's political subjectivity, but also at occupying an area important for economic reasons. The dispute over Bohumín was also proof of the lack of an agreement between Warsaw and Berlin.

The demonstrative Soviet offer to provide Czechoslovakia with armed assistance based on the provisions of the treaty on mutual assistance linking Prague with Moscow since 1935 also had no chance of implementation. Such actions would be possible only after France became militarily engaged in the defence of the ČSR, however France’s leaders did not consider at all - as has been shown above - the implementation of such a scenario. Therefore, the Polish authorities' lack of consent to the Red Army's march through the territory of the Republic of Poland was not the reason for Moscow's failure to provide assistance. The proposal of the USSR was therefore only part of a series of propaganda measures intended to perpetuate the image of the communist empire as a determined "defender of peace", and the threat of breaking the non-aggression treaty of 1932 made against Poland was part of the policy of intimidation.

The events of the autumn of 1938 should be analysed in the context of the previous ones - they were a consequence of difficult bilateral relations between Poland and the ČSR throughout the entire period of the functioning of both countries on the political map of Europe after 1918. The Republic of Poland entered the lands seized by the ČSR as a result of the invasion of 1919, the annexation of which was confirmed by the Western powers in the summer of 1920, when the Poles were fighting a decisive battle with the Bolsheviks. Moreover, it made its demands only when the Czechoslovak authorities, deprived of the will to defend the territorial integrity of their own state, capitulated to the dictatorship of the powers. It was clear that the ČSR then lost its status as an independent subject of international politics, which was confirmed by the events of March 1939, i.e. the final collapse of Czecho-Slovakia.

The decision to seize Zaolzie, treated as the implementation of justified Polish postulates, was undoubtedly the most difficult of the choices made by those in charge of the foreign policy of the Second Polish Republic.

Basic references:

Beck J., Wspomnienia o polskiej polityce zagranicznej 1926–1939, ed. A.M. Cienciała, Warsaw – Cracow 2015.

Diariusz i teki Jana Szembeka. (1935–1945), Vol. 4: Diariusz i dokumentacja za rok 1938. Diariusz i dokumentacja za rok 1939, ed. J. Zarański, London 1972.

Dyplomata w Paryżu 1936–1939. Wspomnienia i dokumenty Juliusza Łukasiewicza, ambasadora Rzeczpospolitej Polskiej, ed. W. Jędrzejewicz, H. Bułhak, London 1989.

Geneza paktu Hitler – Stalin. Fakty i propaganda, ed. B. Musiał, J. Szumski, Warsaw 2012.

Kamiński M.K., Zacharias M.J., Polityka zagraniczna Rzeczpospolitej Polskiej 1918–1939, Warsaw 1998.

Kamiński M.K., Szkice z dziejów Polski i Czechosłowacji w latach trzydziestych XX wieku, Warsaw 2014.

Kornat M., Polityka równowagi 1934–1939. Polska między Wschodem a Zachodem, Cracow 2007.

Kornat M., Polityka zagraniczna Polski 1938–1939. Cztery decyzje Józefa Becka, Gdańsk 2012.

Monachium 1938. Polskie dokumenty dyplomatyczne, ed. Z. Landau, J. Tomaszewski, Warsaw 1985.

Pilarski S., Między obojętnością a niechęcią. Piłsudczycy wobec Czechosłowacji w latach 1926–1939, Łódź – Warsaw 2017.

Polskie dokumenty dyplomatyczne 1938, ed. M. Kornat, współpraca P. Długołęcki, M. Konopka-Wichrowska, M. Przyłuska, Warsaw 2007.

There should be avoided references to publications in which the Polish side is presented as a state co-responsible for the weakening of Czechoslovak statehood and containing the thesis about the existence of a Polish-German agreement on the division of the territory of the First Republic:

Batowski H., Rok 1938 – dwie agresje hitlerowskie, Poznań 1985.

Chlebowczyk J., Rok 1938 a sprawa Zaolzia. Refleksje, “Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. Prace Historyczne” 1987, bulletin No. 83.

Raina P., Stosunki polsko-niemieckie 1937–1939. Prawdziwy charakter polityki zagranicznej Józefa Becka, London 1975.

Stanisławska S., Polska a Monachium, Warsaw 1964.

Stanisławska S., Wielka i mała polityka Józefa Becka (marzec – maj 1938 r.), Warsaw 1962.

Tomaszewski J., Polska wobec Czechosłowacji w 1938 r., “Przegląd Historyczny” 1996.

Sebastian Pilarski, Ph.D.