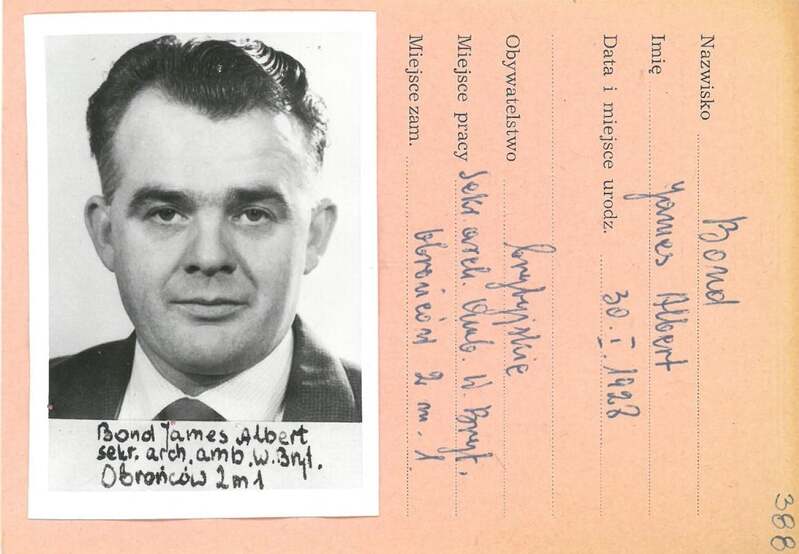

James Albert Bond from Devon came to Warsaw in February 1964 with his wife and six-year-old son, to take the position of a secretary-cum-archivist to the military attaché at the British Embassy. During his time here he made a few trips to northeast Poland, accompanying senior staff of the local SIS (Secret Intelligence Service) station, allegedly to gather information on military facilities there. As an imperialist diplomat, Bond was automatically put under surveillance by Department II (Counter-intelligence) of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, which noted his talkativeness, caution and penchant for women. They recorded little more: within ten months, the man sent his family back home, and a couple of weeks later departed himself, never to return.

Now, James Bond’s legend was a low-level Foreign Office employee tasked with a mundane archivist’s job, and a family man who couldn’t take separation from his wife and son when posted behind the Iron Curtain. The second layer was a junior intelligence officer who personally gathered information on the Polish Army – which was plausible, just. Only just, because Western Intelligence had been deep into such activity nearly a decade earlier, when a possibility of communist forces sweeping into Western Europe looked frighteningly real. Back then, the SIS personnel in Warsaw regularly took trips to the countryside to take photos, make maps and gather any scraps of information on the army units and training grounds. They were equally interested in the railway lines: in the opinion of the Joint Intelligence Committee’s expressed in their 26 January 1955 memo, nothing short of nuclear bombing of fifty key junctions in Poland could neutralize the Red Army’s mobility.

However, by mid-1960s the situation had somehow normalized, and the communist offensive was no imminent threat any longer. Naturally, intelligence personnel in Poland were as interested in the army potential as ever, but they preferred to rely on well-placed sources than personally take snapshots of army barracks – and so their trips to the countryside had become more of leisure pursuits than serious espionage. Such was the scene to which Sir Richard White, the SIS Head at that time, authorized sending a low-level operative with a high-profile name. Ian Fleming’s blockbusters had been around for over a decade and it stood to reason that even the communists had read them, and if not, that at least they’d seen the Sean Connery movies. Therefore James Bond came to Poland lit up like a Christmas tree and bound to draw attention; even if Department II or Internal Military Service didn’t really believe that obvious ruse, they still couldn’t afford ignoring the man and neglecting surveillance.

And perhaps that was the third layer of James Albert Bond’s identity: the role of a smokescreen, or a dangle that would force the communists to relocate assets, or at least move the more efficient teams to watch the secretary-cum-archivist on his exploits in Warsaw bars and trips to the countryside, leaving the clumsier operatives on a case, person or place that Sir Richard perceived as much more sensitive. Well-informed opinion has it that the organization process of Intelligence services in communist Poland had not been completed before mid- 1960s – and perhaps in 1964, counter-intelligence was not quite there in terms of their tradecraft either, or at least they were far enough to allow the SIS to put reasonable hopes into Operation 007. It wouldn’t be the first time – and certainly not the last – when spooks used disinformation to fool spycatchers.

We might never know if Warsaw was simply an uneventful episode in the career of a young spy, or whether Sir Richard White had planned for the communists to put Bond under close surveillance. The only thing that appears fairly certain is that while Ian Fleming had put espionage into fiction, British Intelligence put fiction into espionage.