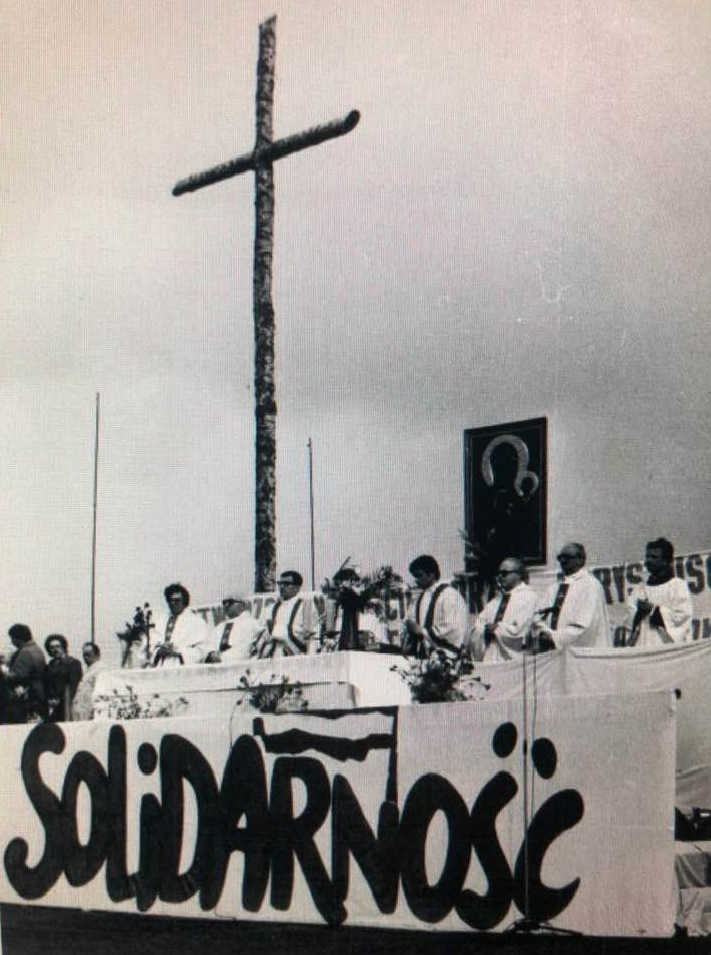

The faces of people gathered on 15 August 1981 in Ossów look very attentive. The oldest of them must still remember the horror and joy from over sixty years ago. Several dozens photos stored at the IPN Archive show tens of people standing next to the monument of Father Ignacy Skorupka, which was rebuilt at the times of Solidarity, after it had been destroyed by communists. Father Wacław Karłowicz, who was thirteen in 1920, is delivering a speech. Next to him, an elderly man in an uhlan uniform is standing at attention ‒ he enlisted as a seventeen-year-old in the Volunteer Army of General Józef Haller. It was quite similar in summer 1981 in Płock, where a fourteen-year-old defender of the city, Antoni Gradowski was commemorated, and in so many other places of victory over Bolshevism. First official celebrations after 1939 were rendered possible after the Solidarity movement was established ‒ thanks to it the memory of the greatest triumph over communism, the triumph pushed into oblivion for so long, started to regain its rightful place.

“Who is winning? Poles or ours?”

Independence, newly-regained in 1918, faced a mortal danger, threatened by the approaching Bolshevik army. The danger was additionally enhanced by an unfavourable internal situation. Apart from a material and humanitarian disaster, there was lack of the spirit of the nation, made up by people ‒ as writer Adam Grzymała-Siedlecki noted ‒ “ those who speak Polish and who can speak Polish only, considered naturally the citizens of the Polish Republic, but owing to the years of captivity and its consequences – not mature enough to show patriotic feelings. Their children, their grandchildren – will be Poles of their own volition and feelings – whereas they themselves are Poles solely due to the language they speak.”1

It was them who asked in summer 1920: “Who is winning? Poles or ours?”, it was them who deserted from the army, it was them who waited for the Bolsheviks, dazed by their slogans. There were numerous people described by Eugeniusz Małaczewski, a soldier and writer, in the following way “the eternal cause, that is Poland, they measure with a decrease or increase in the value of currency. For them Poland is dying when the price for basic necessities amounts to this much, whereas yesterday it was only that much. These are the same people who in November 1918 called faith in the Independence of Homeland madness.”2

In the dramatic moments of 1920 they belonged to the most numerous party, colloquially called the OPB party, that is “Onufry, Pack your Bags”.

Ruins and hunger

The state without borders, on the lands affected by war damage, destitution, hunger and epidemics, was built by Poles who for more than a century had lived at the peripheries of three powers representing different cultures, different levels of development and different mentality. So Poles faced a task to bring together the post-partition lands, to promptly organize diplomacy indispensable to negotiate the borders, a unified army to defend them, a legal and economic system as well as education. During the First World War fighting took place on 90% of the territory of the future Polish Republic, and on 25% of the land (100 thousand km²) the fighting was extremely bloody and long-lasting. In the most affected regions about 40% of residential and farm buildings were destroyed. The industrial infrastructure was ruined. Bare walls and empty halls were all that remained after many manufacturing plants, sometimes even the floors were wrecked. The metal industry in former Congress Poland ceased to exist. The Russians took away everything ‒ from machines to the simplest parts of the equipment. There was no transportation network that would consolidate the post-partition lands into one entity; 60% of railway stations were destroyed. The partitioning powers cut down more than 2.5 million ha of forests in an exploitative way. They took farm cattle and horses with them, the number of animals fell by at least 30%. Fallow land amounted to 3.5 million ha, and the harvest could cover only half of demand for flour.3The shortage of coal, rather common in Europe at that time, was also very severe in Poland – and coal was the raw material necessary to launch production and transport; the coal extraction decreased, we could cover only 40% of demand and coal prices went up by almost 500%. Out of fourteen steelworks only one was working – in Częstochowa. Iron production and forged products manufacturing fell from 470 thousand tonnes to 19 thousand tonnes. Till spring 1920 only 18% of the mechanical industry was launched as compared to the situation before the First World War, as well as 20% of the textile industry, 27% of the construction industry, 32% of tanneries, 36% of the chemical industry and 41% of the food industry. That year budget revenue covered merely 13% of the expenses, the rest was a deficit. Prices were soaring ‒ as compared to 1914 they increased by 3,000%, and only between July 1919 and spring 1920 ‒ by 200%.4

The monument of Father Ignacy Skorupka in Ossów by Czesław Dźwigaj (photograph by Sławek Kasper)

Hunger plagued the poorest. Weakened organisms were decimated by diseases, more fatal than fighting on the front line. In poor Eastern Lesser Poland (Małopolska) at least 400 thousand fell ill with typhus, with the mortality rate around 15‒17%. The army lost 2,348 soldiers and officers who died in the East between 1 October 1919 and 30 June 1920, and 1,744 were wounded, whereas diseases, among them typhus and dysentery, caused 93,636 deaths of the military. One doctor died every day, combating the diseases. Doctors younger than 35 years of age were delegated to take care of patients as for older doctors it would frequently be a death sentence.5

Everyone against everyone else

The bureaucratic maze of a young state, which regulated life by means of official orders, and the market reacting with sudden price shocks were also part of the picture. Food rationing, shortage of goods and several currencies in circulation at the same time created an ideal situation for speculation. The areas of extreme poverty were contrasted with fast-growing fortunes of the nouveaux riches. Strikes spread throughout the country. In June 1920, after the Bolsheviks conquered Kiev, Warsaw was paralysed by a strike of municipal services. Streets were drowning in rubbish. The power plant, gasworks and waterworks ceased to operate. Patients in hospitals were deprived of water, electricity and gas. Other cities joined in the protests, telephones fell silent, bakeries stopped baking bread. Even rationed bread was no longer available.

Under such conditions Bolshevik agitation intensified. Communists made a failed attempt to interrupt work of mines in the Dąbrowa Basin. The tense situation was alleviated to some extent thanks to thousands of members of the Society of Social Self-help who replaced workers. The capital power plant was re-started thanks to the army. Chaos and anarchy began to scare even those who had previously tried to destabilize the state. A socialist paper “Naprzód” wrote towards the end of June 1920: “Social and moral ties are dissolving. A dreadful civil war broke out, of everyone against everyone else”.

The situation was no different in the fragmented Sejm (the Polish parliament), which quite recently, on 18 May 1920, welcomed Józef Piłsudski coming back from Kiev. The Speaker Wojciech Trąmpczyński declared: “The entire Sejm, through my lips, welcomes you, Commander-in-Chief, returning from the route of Bolesław the Brave […]. History has never seen a country that would establish its statehood under such difficult circumstances as ours.”6 Unity at the moment of victory did not last for long ‒ three weeks later Leopold Skulski's government tendered its resignation, which coincided with recapturing Kiev by the Bolsheviks. In the East the Polish Army began to withdraw. At the same in Warsaw the Sejm was unable to form a majority coalition almost until the end of June.

Help its own defeat

As Adam Grzymała-Siedlecki wrote:

“The country seems to have vowed to help its own defeat. Disgrace of our young independent life […]. In villages, among peasants, especially those without land, blunt agitation in favour of the Bolsheviks and clandestine instigation against the organised military conscription. At the top, in the government and the Sejm – discord.”7

General Stanisław Szeptycki, who arrived in Warsaw for a short time from the front near the Berezina River, in his interview for the “Rzeczpospolita” paper expressed his surprise at the sight of the city. The youth filling cafés and streets – as he said – could shortly form divisions, so necessary at the front line. The war is waged on two fronts: the internal and the external one. When the first one does not exist, the war cannot be won ‒ he stressed. The internal front started to take shape only after the horror of the situation intensified. On 24 June, when the Polish Army was barely able to stop the Bolshevik Western Front in Belarus, and it had to surrender Zhytomyr to Budyonny's 1st Cavalry Army after bloody fights, and the great retreat of the army to the West started, a government of Prime Minister Władysław Grabski was formed. Grabski said in his exposé: “ it is time today for the nation to shake off […] its light-hearted attitude towards the most basic issues of its existence. […] People enjoy themselves more than before the war. They walk calmly, make demands, think only of temporary enrichment. […]. And it is happening not only in the capital, not only in cities, it is happening everywhere.”8 But the nation woke up. The following week the State Defence Council was set up and soon its first announcements were issued, signed by the Chief of State and Commander-in-Chief Józef Piłsudski: “Everything for victory! To arms!”. In the following days the whole country was agitated. There were numerous appeals, conscription started – in the Voluntary Army and the services which were to work for the army. Money was raised for the fighting army.

Celebrations in Ossów on 15 August 1981 with participation of an uhlan who took part in the Battle of Warsaw (a photograph from the IPN collection)

The youth were the first to respond to the call “To arms!”: middle school and university students, scouts. A huge response came from higher schools. “To arms!” – appealed the Senate of the University of Warsaw. Soon the University League of State Defence was created; it organized students' conscription in the army and auxiliary service. The Jagiellonian University, the University of Poznań, the Technical University of Lvov, Jan Kazimierz University, the Higher Forestry School, the Higher School of Commerce or the Stefan Batory University of Vilnius did not remain passive.9 Soon scholars and students were joined by writers, actors, artists – representatives of the elite of that time. The intelligentsia was a very numerous group then.

The Jasna Góra Entrenchment and OKOP

Bishops gathered at the Jasna Góra shrine pointed out to Poles that there was an invincible spiritual weapon: “Let the power of our prayers bring triumph and victory to our Homeland”. In thousands of churches a letter about the enemy was read out, the enemy who – as bishops emphasized “combines cruelty with lust for destruction of all culture, especially Christian culture and the Church. Murders and slaughter follow in his footsteps, his traces are marked with burning hamlets, villages, and cities but most of all, he chases, in his blind persistent envy, all wholesome social relations, every seed of real education, every wholesome system, all religion and the Church.”10

Consecutive initiatives mobilised people to fight with communism, among them the Citizens' Committee for State Defence (the Polish abbreviation was OKOP, which means a trench). This structure was used by the Volunteer Army as a supply department and organisational backup. Finally,“the Polish Army had a social wall behind them, and they could support their back against it”11– as Ignacy Oksza-Grabowski, head of the OKOP Press Section, explained.

From 10 to 17 July almost 30 thousand volunteers responded to appeals, by the end of the month – almost 65 thousand. After a field mass on 18 July, volunteers set off from Warsaw to the front. Crowds knelt and the supplication Święty Boże, Święty Mocny (Holy Father, God Almighty) rose up in the air. The first squadron of a voluntary regiment of uhlans departed from Płock. Łowicz sent its scouts. The conscription action was expanding in Greater Poland (Wielkopolska) and Pomerania (Pomorze). In Grudziądz and Toruń, after field masses, conscription points accepted volunteers. In Konin almost all students from senior years of middle schools volunteered.

“There was something magnificent in this march of the youngest under the banners ‒ Grzymała-Siedlecki recalled. ‒ As if it were a crusade, inspiring everyone who can carry arms. And frankly speaking, there were those among them who were not strong enough for strenuous military service. There were boys among them, bloodless, emaciated owing to poverty of the intelligentsia families in which they were born: some suffered from consumption, others from weak heart; there were those who were fragile and haggard, exhausted from learning. Some of them were almost children. None of them took a step back.”12

Within just a few weeks the nation mustered the forces which stopped the Bolsheviks. Before the decisive battle, the Prime Minister Wincenty Witos visited troops near Warsaw. Near Radzymin he saw the weakest section, at which soldiers incurred significant losses and did not have any successes, “which generated a psychology of weakness and fear among them, that they could not get rid of” ‒ he wrote13. The mood was entirely different among those preparing to attack Nasielsk. The Prime Minister recalled: “Only a fraction of soldiers had full, yet shabby uniforms, at least half of them were without shoes, marching with bare, injured feet on sharp roads and rye stubble. […] on some only shreds of trousers and other clothes were hanging. But all of them had rifles and cartridges, and in a conversation they displayed a great confidence and faith in their victory.”14 And they triumphed over the Bolsheviks.

“Deprived of their homeland”

Less than two decades after the Warsaw victory, a generation brought up in the independent Polish Republic had to make a sacrifice once again, as they did not give their consent to captivity ‒ from 1939 the German and Soviet occupation and from 1944, in post-Lublin and then post-Yalta Poland, when Moscow gave authority to their governors ‒ successors of traitors, about whom Stefan Żeromski wrote in 1920: “Who brings the eternal enemy to his homeland, even though sinful and evil, who trampled his homeland, crushed it, plundered, burnt, looted with the hands of foreign brutish soldiers, he deprived himself of his homeland.”15

The crowds of those “deprived of their homeland” created a mechanism of the security service and violence, built communism in literature, science and art, poisoned social consciousness with universal lies for almost half a century. It was them who liquidated independent elites and pushed them to the margin, taking their place. A certain communist milieu gathered around them – people uprooted from their environments, without principles, conformists and cynical careerists, who obtained their positions only thanks to their faithful service to the system. Communists could boast of numerous artists, scientists, writers and journalists, who supported them. Numerous praisers gave credibility to the Polish United Workers' Party (PZPR) thanks to their popularity, legitimized the authorities and willingly took advantage of their privileges. Communism destroyed the minds of millions of Poles, who did not see a possibility of changes due to the memorable experience of Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968 and domestically ‒ due to bloody suppression of protests in 1956 and 1970 as well as the one in 1976, pacified by means of “fitness trails” (or running the gauntlet). People tried to find their place in life, often ending up implicated in dependence on the system.

In the 1970s a generation born towards the end of the Second World War or right after that started an adult life – so these were people who did not remember independent Poland, thus they were more susceptible to communist propaganda. The efficiency of sovietisation required breaking the links with the Polish independence tradition. Therefore, the milieu of veterans was marginalized. There are volumes of documents of the security service – quite revolting to read – which describe activities against elderly people – soldiers of the Legions and participants of the Polish-Soviet war. Whole chapters of history were falsified, some of them were obliterated. Censorship did not allow to print “information and mentions about the following distinctions, introduced and awarded in the past by the authorities of bourgeois Poland, a government in exile or emigration organizations in exile […] 3. the Volunteer Cross for War (1918‒1921), 4. the Volunteer Medal for War (1918‒1921), the Commemorative Medal for War (1918‒1921)”.16

It was the reality in which Stefan Kisielewski in his Journals of 1977 asked a question:

“Aren't we all perhaps degenerated? If for thirty years we accept the status quo, living in it, the status quo in which we call white – black, dictatorship – democracy, rape – friendship, etc., there must be some psychological consequences.”17

Economic issues were clear manifestations of a crisis – absurdities of the economy, dependence on the Soviets, debt, queues… Other consequences were often neglected as less measurable, yet they were far more dangerous: ruined work ethos, reversing the system of values, ubiquitous lies which demoralised more efficiently and degenerated more permanently than empty shelves. An ideological school and universities teaching conformity used the language of propaganda.

When symptoms of the crisis were more prominent in every sphere of life, words of criticism made no impression on the authorities. Memorials of representatives of the Church and letters written by independent milieus, describing a tragic situation of the society, were hidden in drawers and their authors and signatories were persecuted.

“Summary of our weaknesses”

“Growing economic difficulties […] and phenomena of social life disorganization have a clear connection with manifestations of a serious moral crisis. What is striking among them is disregard for the truth in human relations, the deteriorating condition of social integrity: unreliable work, lack of a sense of common good, corruption, alcoholism, general discouragement, deepening indifference towards human and social needs and lack of kindness in human relations.”18

That is what bishops wrote towards the end of the 1970s. They highlighted a disastrous demographic situation, made worse by 300‒800 thousand abortions a year; emphasized that “national dignity is born especially out of a sense of one's own history, out of respect for one's own culture and spiritual and religious heritage”,

that the “unity of a nation is not possible if history, culture and religious legacy of the nation is distorted and permanently subordinated to Marxist ideology.”19

Professor Edward Lipiński, a doyen of Polish economists, in the past – an activist of the Polish Socialist Party, later a member of the Polish United Workers' Party (PZPR) and then one of the founding members of the Workers' Defence Committee (KOR), described the situation similarly. In his article of 1977, Fictions and reality, he noticed the creation of “an artificial vocabulary, expressing imaginary reality”, and a language of “false awareness”. He enumerated the spheres of decline one by one: “housing disaster […], underdevelopment of hospitals, ruined work morale, disturbing condition of transportation […], destruction of agriculture, destruction of small-scale industry and craft […], severe crisis of supplies and inflation […] too common manifestations of corruption, alcoholism, and moreover – cancer of bureaucracy, depriving the nation of credible information”.20

In this overwhelming reality of 1977, a text by Andrzej Kijowski was published, it was entitled Summary of our weaknesses, signed by the Polish League for Independence ‒ copied on a typewriter outside of censorship's reach. His words were read by several hundred or a few thousand Poles. The article gave hope which till 16 October 1978 – the day Cardinal Karol Wojtyła was elected Pope ‒ was very much missing. Kijowski wrote: “We know repetitions of our history by heart. However, apart from collective impulses, which were shaped under the influence of these repetitions – hiding into one's private life, looking for compensation in derision and deception, in drunkenness and cynicism – examples of great stances were also shaped. They were shaped not only at battlefields, but also in everyday, persistent work for our homeland. Our history is not made up by inertia, cynicism and private interests, but by people who sacrificed their lives for healing our social and economic relations, to oppose administrative and school violence, people to whom we owe the fact that Poland – despite everything – is still Poland worth living for.”21

Workers vs. Polish cause

Millions of people learnt about such Poland – free from “inertia, cynicism and private interests” – and about a path to it, when they listened to the Pope's words in June 1979. They did not only hear about that, but also noticed that reality around them for a few days. In order to retain that, people had to overcome their fear which was not unjustified.

A photo from the IPN collection

The memory of the bloody suppression of the revolt of December 1970 was very much alive – not only at the Polish Coast. The older generation remembered Poznań 1956. The fates of people ready to oppose the system, such as Stanisław Pyjas or Tadeusz Szczepański – the same age as volunteers from 1920 – proved that the system would resort to crime, if challenged. A small group of the unsubmissive – who decided to openly speak against the regime – included not more than several hundred people throughout Poland; it increased to a few thousand at best, if one counts readers of the underground press or participants of commemorative masses and marches on 3 May and 11 November. It was still not sufficient to disrupt the system, and workers – despite the Free Trade Unions and their activity – were not held in the highest regard by the milieus of oppositionists.

Jacek Bocheński in an underground magazine “Zapis”, in his text written in November 1980, reflected a detached perspective of the Warsaw oppositionist elite looking at the world of workers: “Apparently workers could not achieve more than the rare, chaotic and futile rebellions, during which they took over the party's committee for half an hour, to empty it of the stocks of cold meats and set it on fire. They understood their handicap as a lack of access to party buffets and directors' summer houses. Their aspirations did not reach deeper, because they were successfully dulled by the system, cut off from any higher values, degenerated with drunkenness, illegal dealings and theft. Their sense of justice or dignity pertained to a portion of food, the famous sausage, which was rationed to everyone, but not to civil liberties that they knew nothing about.”22

It was similar to the image of workers upheld by the authorities. The workers' moral condition was perceived in a slightly more favourable light by editors of “Bratniak”, a newspaper of the Young Poland Movement, perhaps because in Gdańsk they were closer to the workers due to the activity of the Free Trade Unions. The editors knew the workers' power but ‒ as we read in an editorial article ‒ doubted “that […] they can formulate a programme of national recovery and shoulder the main burden of its implementation. […] We knew that they were patriotic, that words such as «Poland», «nation» – have a real meaning for them. But is it enough for them to undertake the fight on behalf of the whole Nation, in the interest of all Poles?”.23

“We will have a bit of freedom”

History proved that patriotism of workers was more than ample. The spark that ignited a protest in July 1980 was the announcement of price hikes, but in mid-August the Great Strike in Gdańsk and other solidarity protests removed all the doubts which the intelligentsia may have had.

“In August 1980 several things took place, and previously wise people had said that they were impossible to happen. No reasonable, responsible, experienced and well-informed «realist» took them into account”

– Bocheński noted.24

Workers made demands connected with social issues, but they also demanded dignity, truth, freedom. Writer Lech Bądkowski, after he had read a resolution of the Section of the Polish Writers' Union in Gdańsk, was enthusiastically accepted by acclamation as a member of the Presidium of the Inter-Enterprise Strike Committee, which seems symbolic. In protesting factories, which set an example of self-organization, seriousness and responsibility, people became better, kindness – so rare so far – started to appear. Holy masses, prayers, crosses in production halls, paintings of the Mother of God and John Paul II on gates of factories, then return of statues of St. Barbara, St. Florian, symbols on trade unions' banners with images of the Virgin Mary ‒ it all showed the foundations to which the protest referred. The religious song Boże, coś Polskę (God who saved Poland) sung so many times, with a verse “May you return our free Homeland to us, oh Lord” set a far-reaching goal, not specified in the 21 postulates. A lawyer Jan Olszewski, when he saw white and red banners on the factories on strike, and workers with white and red bands on their arms, and when he witnessed the atmosphere in the shipyard, was reminded of the moments experienced in Warsaw after 1 August 1944.

The accords signed in Szczecin, Gdańsk, Jastrzębie-Zdrój and Dąbrowa Górnicza for the first time gave a chance to workers in the Soviet block to set up their own organization and its establishment gave people hope for change. In the film Workers ’80, right after the scene of signing the Gdańsk Accords, a soldier of the 1st Vilnius Brigade of the Home Army, Henryk Mażul says, wiping away his tears: “How should I put it, a bit of a Polish day arrived… after so many years… we will have a bit of freedom”.

And “a Polish day arrived”. Before several weeks passed, everyone lived in a different country ‒ changed by a wind of freedom, which lasted for sixteen months. That time was not a “carnival” as it is often called ‒ it was filled with hard work of many milieus, selflessly involved in the restoration of the Homeland, ruined by communists. People believed that their actions made sense. The time of hope revealed fiction of the red ideology. It did not bring about the death of invaders, like in 1920, yet did the atmosphere of awakening and enthusiasm not resemble the one from the summer of 1920? Perhaps it could be described by the words of a columnist from the “Kurier Warszawski” daily in July 1920: “A new spirit is marching throughout the country. A great revolution of brains and hearts has begun. […] A new spirit! Every Polish house is a marvellous change. Eyes sparkle differently! A pulse is beating differently. Imagination of the nation is dreaming differently. Pettiness dwindles, greatness is born.”25

The vocabulary of the most Polish words

Communism broke the continuity of the identity shaped throughout centuries ‒ the one that gave rise to the victorious spirit of 1920. The system imposed on Poland in 1944 intended to cut it off from the European tradition. The Solidarity movement, in a broad sense, rebuilt this breached bond, exceeding the realm of social issues in its declarations and activities. In October 1980, the signatories of the August Accords, among them Andrzej Gwiazda, Anna Walentynowicz and Lech Wałęsa, arrived in the south of Poland. The holy mass in the Basilica of Sts. Stanislaus and Wenceslaus at the Wawel hill, a visit at the Jagiellonian University and the Jasna Góra shrine emphasized the pan-national nature of the movement. At Wawel, among the tombs of Polish kings, the delegation listened to a sermon delivered by Father Józef Tischner. The author of Ethics of Solidarity said:“The word «solidarity» joined the vocabulary of the most Polish words to give a new shape to our days. There are several words like that: «freedom», «independence», «human dignity» – and today the word «solidarity». Every one of us feels a great burden of meanings hidden in this word. The meaning of the word is defined by Christ. Carry each other's burdens, and in this way you will fulfill the law of Christ. What does it mean, to show solidarity? It means to carry a burden of another human being”.

The leaders of the trade unions listened to the message which was developed further in papal sermons in the coming years… Father Tischner explained: “We are experiencing an extremely difficult time now. People remove masks from their faces, leaving their hideouts, revealing their real faces. From under the dust and oblivion their consciences come to light. Today we are who we really are. What we are going through is not only a social or economic event but especially an ethical one. […] The deepest solidarity is the solidarity of consciences.”26

Restitution of memory

Then an enthusiastic crowd, thousands of people, walked the Royal Route, carrying Lech Wałęsa – then unaware of his previous relations with the Security Service – on their shoulders to the Main Square. On the square, in the place in which Tadeusz Kościuszko took an oath in 1794, the guests from the Coast made a vow, and Alina Pienkowska said: “We swear to you, Commander-in-Chief, that we will not fail the society that trusts us and, in order to fulfill our obligations, we repeat after you: So help us God, and innocent martyrdom of His Son. Amen.”

The route that the leader of August strikes took from royal tombs at the Wawel hill, through places connected with the Kościuszko Uprising, to the Kraków Alma Mater, and then the Jasna Góra shrine, marked clearly a cultural foundation on which Solidarity was based; it was also part of the mainstream Polish history.

Solidarity, demanding dignity, restored not only the memory of the Polish-Soviet war, but primarily continuity of the Polish national identity and tradition, and returned a stolen meaning to words. The manifestations of these attempts were the Monument to Fallen Shipyard Workers in Gdańsk, the Monument to the Victims of December ’70 in Gdynia, crosses in Poznań, commemorating the revolt of 1956, and so many other places of commemoration throughout Poland ‒ and apart from them, thousands of books and bulletins printed out of censorship's reach and presence of history in almost every issue of underground papers.

Solidarity gave rise to wonderful stances and brought back many heroes, also the heroes of 1920. They still appeal to us, like in a poem Polish wings by Ernest Bryll, sung at the time of the martial law, when the poem had a life of its own:

And these wings are like the banners

Of independent old faith

Still shining, still shining!

And the bloody wings

In many battles wounded,

Although shrank and lost lustre

Yet didn't lose their power.

They are like before,

Like wings of former glory

They can carry us!

They carry us further.

The text is derived from “The IPN Bulletin”, issue 7-8/2020

1 A. Grzymała-Siedlecki, Cud Wisły. Wspomnienia korespondenta wojennego z 1920 roku, Łomianki 2008, p. 161.

2 Koń na wzgórzu, [in:] E. Małaczewski, Opowieści z wojny polsko-bolszewickiej 1920 i inne wojenne historie, Kraków 2020, p. 234.

3 E. Kołodziej, Gospodarka wojenna w Królestwie Polskim w latach 1914‒1918, Warsaw 2018, p. 172.

4 “Przegląd Gospodarczy. Organ Centralnego Związku Polskiego Przemysłu, Górnictwa, Handlu i Finansów” 1920, pp. 1‒9.

5 J. Wnęk, Pandemia grypy hiszpanki (1918‒1919) w świetle polskiej prasy, “Archiwum Historii i Filozofii Medycyny” 2014, no. 77, pp. 16–23; idem, Epidemia czerwonki w Polsce w latach 1920‒1923, “Przegląd Epidemiologiczny” 2017, no. 1, p. 136; The Józef Piłsudski Institute in America, Józef Piłsudski's Collection, file: The Cabinet of the Minister of Military Affairs, reports, proclamations, orders, correspondence, sketches, fragment of a banner, 701/1/57, A diagram of losses among officers and lower military ranks in the Polish-Bolshevik war of 1919‒1920.

6 Stenographic record of the sitting no. 148 of the Parliament of 18 May 1920, https://bs.sejm.gov.pl/exlibris/aleph/a22_1/apache_media/2K1PU2LJMACD9TYQB3U8EJALRJVML9.pdf [access: 23 June 2020].

7 A. Grzymała-Siedlecki, Cud…, p. 156.

8 Stenographic record of the sitting no. 156 of the Parliament of 30 June 1920, https://bs.sejm.gov.pl/exlibris/aleph/a22_1/apache_media/T5E83VUY4H6M4IBF21EIPDKVIIB7TT.pdf [access: 23 June 2020].

9 Bij bolszewika. Rok 1920 w przekazie historycznym i literackim, collected and compiled by Cz. Brzoza, A. Roliński, Kraków 1990, p. 250.

10 List pasterski biskupów polskich do narodu, 7 VII 1920 r., [in:] Metropolia warszawska a narodziny II Rzeczypospolitej, Warsaw 1998, pp. 211–214.

11 Obrona państwa w 1920 roku. Księga sprawozdawczo-pamiątkowa Generalnego Inspektoratu Armii Ochotniczej i Obywatelskich Komitetów Obrony Państwa, Warsaw 1923, p. 594.

12 A. Grzymała-Siedlecki, Cud…, p. 159.

13 W. Witos, Moje wspomnienia, v. 2, Paris 1964.

14 Ibidem.

15 S. Żeromski, Na probostwie w Wyszkowie, Warsaw 1981, p. 22.

16 T. Strzyżewski, Czarna księga cenzury PRL, Warsaw 2015, p. 93.

17 S. Kisielewski, Dzienniki, Warsaw 2001, p. 576.

18 Communiqué of a plenary session of the Conference of Polish Bishops on deteriorating social situation in the country, [in:] P. Raina, Kościół w PRL. Dokumenty 1975‒1989, Poznań-Pelplin 1996, p. 147.

19 Memorial of a plenary session of the Conference of Polish Bishops to Prime Minister P. Jaroszewicz on biological and moral threats for the Polish nation, [in:] ibidem, p. 81.

20 E. Lipiński, Problemy, pytania, wątpliwości. Z warsztatu ekonomisty, Warsaw 1981, p. 645.

21 [A. Kijowski], Rachunek naszych słabości, Zespół programowy PPN, n.pl, 1977.

22 J. Bocheński, Co za nami, co przed nami, “Zapis” 1981, issue 17.

23 Sierpniowe refleksje, “Bratniak” 1980, issue 25.

24 J. Bocheński, Co za nami…

25 W. Rabski, Walka z polipem. Wybór felietonów (1918‒1924), Warsaw 1925, p. 184.

26 J. Tischner, Etyka solidarności, Kraków 1981, pp. 12–16.