During a pandemic, issues such as historical publications become of secondary importance, giving way to other aspects of our social life. That is why the launch of Jan Grabowski's book Na posterunku. Udział polskiej policji granatowej i kryminalnej w zagładzie Żydów has gone by practically unnoticed. The author, who has been dealing with the subject of the Holocaust in Poland for years, is as well-known as he is controversial. His theses, concerning the conscious and voluntary participation of Poles in the Holocaust, presented in the book Judenjagd. Polowanie na Żydów 1942–1945. Studium dziejów pewnego powiatu (2011) and the collective work edited by him and Barbara Engelking Dalej jest noc. Losy Żydów w wybranych powiatach okupowanej Polski (2018) – have sparked off numerous disputes.

The Blue Police in source materials

This time the author has taken up the topic of the Polish Police in the General Government (the so-called Navy Blue Police, formally established by the Germans under the name Polnische Polizei im Generalgouvernement) and the Polish Criminal Police (Polnische Kriminalpolizei – the so-called Polish Kripo). According to Grabowski, only the spontaneous and voluntary participation of these formations in the German extermination apparatus allowed it to operate on such a large scale and with such tragic consequences for the Jewish population.

Moreover, Grabowski attributes voluntary and active participation in the Holocaust to e.g. volunteer fire brigade units. In the introduction he writes: “It is at this stage that one must reflect upon the sense of the often-repeated claim that ‘no Jew could have survived without the help of Poles’. Was this really the case? Many Jews managed without Polish aid, displaying great entrepreneurship and independence. They did not seek help; one could even say that they were counting on Polish indifference. However, we can look at the same issue from a different perspective and rephrase the above statement as follows: is it not true that almost all the Jews who escaped from the ghetto, removed their armbands and took refuge on the Aryan side, died with the complicity of Poles?”

It could be expected that an attempt to show the scale of the crimes committed by an entire formation functioning in the General Government is a task which would surpass the capabilities of an individual researcher. In fact, it requires many years of work on source materials. In addition to those of the pre-war State Police, one should also examine the documents of the German authorities overseeing the newly formed Polnische Polizei and Polnische Kriminalpolizei, as well as materials drafted by both these formations. One should also take into account the testimonies of Holocaust survivors, reports of the intelligence of the Union of Armed Struggle / Home Army; diaries of civilians and – importantly – the testimonies of the police themselves, submitted both before the post-war security authorities, as well as during rehabilitation proceedings or for the needs of veterans' organizations. Although all of the above mentioned sources are included in the bibliography, the author seems to have focused primarily on witness accounts of the survivors, referring to other materials rather sparingly. The Archive of the IPN Branch in Cracow has in its collection numerous documents drafted by the Union of Armed Struggle / Home Army intelligence for Cracow, the intelligence service of the 106th Infantry Division of the Home Army and at least several hundred personal files of former police officers – out of which Grabowski has selected only four (!) units. The use of materials from the Cracow-based Fundacja Centrum Dokumentacji Czynu Niepodległościowego is also rather unclear. Although the author indicates that his query included the archives of the former Historical Commission of the Society of Fighters for Freedom and Democracy , he does not refer to any specific units. Finally - contrary to scientific research standards - the book does not contain any index of names. This makes it very difficult to locate specific cases discussed in the text.

Writing a monograph on a formation which existed in the years 1939–1945, and operated in an area as vast as the General Government, is a huge task. When dealing with the history of the Police (both before and during the war) mainly in Cracow and its vicinity, I am often faced with a vast amount of source material which requires both verification and analysis. Any attempt at such large-scale synthesis made by one person can lead to problems – in particular taking into account the state of preservation of sources, difficulties with access to certain information and the risk of replicating (due to the inability to verify information) various inaccuracies and distortions. Poorly outlined historical context later affect the main theme of the work, which leads to erroneous research conclusions. I will, therefore, analyze Grabowski's work primarily through the prism of Cracow, which is also my field of research, and those fragments of the book which refer to the general situation.

Errors and Inaccuracies

The author is not a specialist in the field of the history of the police. The information he gives, mainly quoting Robert Litwiński (Korpus Policji Państwowej w II Rzeczypospolitej. Służba i życie prywatne [State Police Corps in the Second Polish Republic. Service and Private Life]) and Andrzej Misiuk (Policja Państwowa w Polsce w latach 1918–1938 [State Police in Poland in the years 1918–1938]) regarding pre-war State Police are cited inaccurately or even incorrectly. For instance, he writes: "The State Police also included the autonomous Police of the Silesian Voivodeship and specialized criminal police, or the so-called Investigative Service." It would be hard to make it more confusing. The State Police was a unified service, which included, among others: the Investigation Service (subject to Department IV of the General Headquarters of the State Police, i.e. the Central Office of the Investigative Service), the State Police reserve companies forming the preparatory service corps, and policemen involved in field work and those dealing with office work. In addition, the State Police also employed a team of civilian workers – and that's all. The Police of the Silesian Voivodeship was not and could not be part of the State Police, because they remained an autonomous formation under the authority of the Silesian voivode. The last Chief Commandant of the State Police Kordian Józef Zamorski complained about the lack of this subordination believing that to be one of the reasons for the poor coordination of police activities in September 1939.

Interestingly, the author quotes fragments of Zamorski’s Diaries, indicating his dislike of Jews - a dislike that, according to Grabowski, constituted an institutional element of the police corps' esprit. It is a pity that Grabowski failed to quote any of those fragments of the Diaries in which Zamorski complains about his subordinate policemen, calling them uneducated boors, people without moral backbone. Perhaps he would come to the conclusion that the commandant, apart from anti-Semitism, also promoted the lack of manners and moral degeneracy among his men. A much simpler explanation, such as the well-known misanthropy and the extremely nasty nature of Zamorski (whose entries in the Diaries, discovered after the war by the communist authorities, later caused him a lot of problems – the General offended the entire pre-war establishment in them), apparently has not been taken into account by the author.

Using data on the number of Jewish policemen in the State Police, Grabowski quotes only an outdated survey of 1923, and ignores newer data, presented by Litwiński in his fundamental monograph on the State Police corps. Perhaps because they do not fully confirm the following thesis: "As far as Jews are concerned, actually the only way to join the service or be promoted was through assimilation and baptism." He supports his claim with the example of Józef Szeryński, a well-known neophyte and careerist (during the war, commandant of the Jewish Order Service in the Warsaw Ghetto). The author, however, fails to mention Szeryński’s brother Feliks Szynkman, who successfully headed the Investigative Service in Gdynia, or Commissioner Marian Berch working at the General Headquarters of the State Police. It is also worth mentioning that Superintendent Dr Leon Nagler practically the second person after the Chief Commandant of the pre-war Polish Police was of Jewish origin.

The author reduces all war preparations of the State Police to the bizarre order by Minister Felicjan Sławoj-Składkowski regarding the inspection of farm fences. There is practically no mention about border protection service, the fight against diversion, the mobilization i.e. the police strengthening and protection of railway facilities.

The author briefly mentions the chaos of evacuation, the unsuccessful militarization of the police and the fighting of those who joined the army, and finally the sad fate of policemen who fell into Soviet hands. At the same time, there is neither information regarding the internment of some Polish policemen in Romania and Hungary, nor about the measures taken by the German authorities to recover Polish policemen, who, e.g. were taken from Romanian camps to German Oflags, and from there forcibly transferred to the Polnische Polizei service, which was excellently described in his memoirs by Police Superintendent Kazimierz Mięsowicz[i].

In his work the author makes the basic assumption that German authorities were constantly lacking the strength to control and retain the territory of Poland, and therefore Polish police officers could enjoy relative independence. True, German police forces still obviously demanded strengthening, but this does not mean that they were scarce. It is worth remembering that they were only part of the occupation machine, also established by the occupation forces, the German civil and special administration and (last but not least) also by German civilians living in the territory of the General Government (GG), alongside with a huge number of collaborators and informers. Unfortunately, nowhere in his book does Grabowski include some basic information which could provide a framework for his narrative. A large prize for anyone who finds the information on the exact structure and number of the German police forces in the GG in the paper ̶ in particular, a detailed description of the fluctuation of various police units that took place after the beginning of the war against the Soviet Union. Determining the exact structure and number of forces of the Polnische Polizei and Polish Kripo turns out to be even more of a problem for the author. The general thesis that there were about 10 thousand Polish policemen within the GG, does not reflect the detailed dislocation of the police forces. It is my impression that the omission of this information was intended to build a narrative in which a few German policemen do not have to guard the wild hordes of the Polish "Blue Police".

The author also makes mistakes ̶ it is hard to tell whether they are deliberate ̶ border lining on half-truths. Once he changes thirteen police battalions (about 500 people each) stationing in the GG into thirteen companies (140-150 people each), significantly reducing the number of the German police in the occupied Polish territories. Elsewhere he forgets to mention the various free-formations that passed through the GG over the past five years. Finally, when describing the emergence of the "Blue Police", a fairly heavy distortion is allowed, claiming that it was reestablished, "while preserving its pre-war internal structures"[ii].

The above thesis is ungrounded. First, the highest Polish police structure allowed by the occupier was the poviat headquarters or the city headquarters. Voivodship headquarters ceased to exist, not to mention the General Headquarters. In other words, in the case of Polish policemen scattered throughout the General Government, there was no uniform authority (meaning: due to being entangled in the German police system, they were subordinate to the Senior SS and Police Commander). Importantly , at practically every level, the "Blue Police" stations were subject to the German authorities with regard to the executive service. Therefore, even the existing Polish sovereignty was primarily of a staffing and organizational nature. In fact, the only substitute for higher structures were the so-called liaison officers at the district authorities, who could somehow shape the German personnel policy in the area of specifically filling officer positions. Some of these officers (as exemplified by Lt. Col. Roman Prot Sztaba) used this opportunity for the needs of independence activities.

Unfortunately, there are more similar factual errors. They could be enumerated for a long time̶ ̶such as errors in the description of Józef Wraubek's service, as detailed in his diary, which the author quotes in the same paragraph. Interestingly, in the bibliography of his work, Grabowski defines Wraubek's memories with the title Na Podhalu [In Podhale], indicating them as an undated typescript from his own collection. Well, the title In Podhale (from December 1939 to February 1942) is born only by one of the chapters of the memoirs, listed under the collective title My Memoirs in the resources of the Ossoliński National Institute Library (reference number 14059/II). The author, probably only using a fragment of the memoirs received from a friend, failed to establish the facts related to Wraubek’s life or service which could be found in other chapters of Memoirs .

Errors continue to pile up, for example: the assignment of Wojciech Stano (from 1929 serving in the Kielce region) to the Cracow Investigation Service, an incompetent estimation of the number of both the pre-war Investigation Service in Krakow and the war composition of the Cracow Police Directorate (despite the sources preserved in the National Archives in Cracow), an incorrect description of Lt. Col. Roman Sztaba as the head of the police in Cracow (Sztaba was the liaison officer of the Polnische Polizei, and the function of the city's commander was held by Major Franciszek Erhardt), and the use of the name "Central Investigation Service" (instead of Center of Investigation Service), typical of online descriptions from the National Digital Archives..

It is worse, when the author is using, for example, the "List of officers and rank-and-file workers of the Polish Police serving the German occupier on the territory of the General Government or remaining at his services" for the Cracow District. Not only does he ignore the fact that it was drafted by the intelligence officers who were police officers themselves, but he also fails to relate the figures contained in the list to a total number of police officers in the district. For comparison ̶ the list contains 213 names, and about 3,000 served in the Cracow District police officers. Without such references it is easy to construct a narrative in which almost all "Blue Police" officers are murderers involved in German crimes.

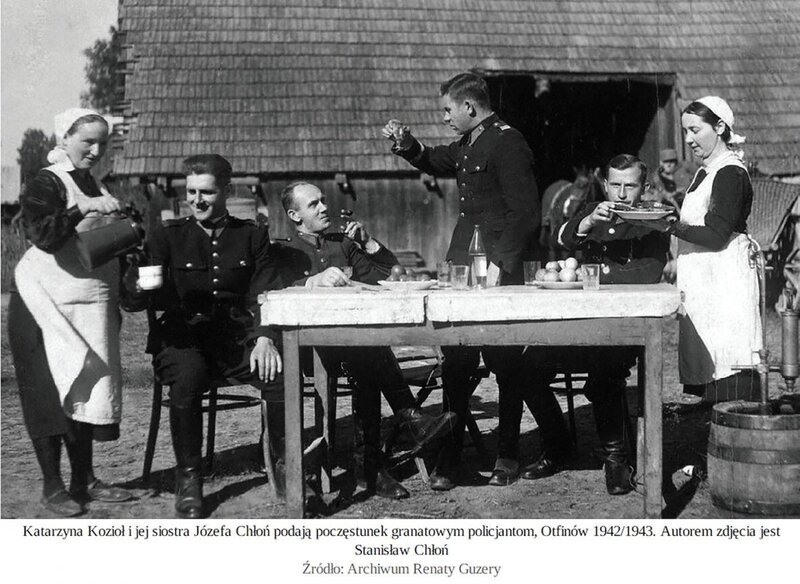

Grabowski writes: "Some photos, as posted on the next page, require discussion and in-depth reflection. Four men in uniforms can be seen behind the table. Two women, festively dressed, who are serving food and drink to the men are standing on each side. Three men are sitting, and one is standing and ̶ with clear respect – is raising his glass, turning towards one of the seated men, who has a slightly indulgent smile. The smiling man is sitting comfortably leaning back, his legs are crossed, and he is smoking a cigar. He is undoubtedly the central figure. Perhaps it is his birthday or name day, perhaps the feast is commemorating his promotion. We do not know that. However, while his comrades are wearing dark blue Polish police uniforms, he is wearing a lighter German military uniform. Then, it is an illustration of the dependence of Poles and Germans serving at one post, and the reflection of the "merging" of Polish policemen into the local community. The undated photo, showing peace and harmony, was probably taken in 1942 or 1943 in Otfinów near Tarnów"[iii].

One should agree with the author that some photos require discussion and in-depth reflection, especially if you want to illustrate a thesis with them. It is worse if you have no idea what they represent. Contrary to Grabowski's claims, in the picture there is not a single German gendarme , because all men are officers of the Polnische Polizei. Indeed, the uniform of one of them seems slightly lighter, but this may be due to the light, or the fabric used to sew it. However, this is certainly not the uniform of the German gendarmerie, but the regulation uniform of the "Blue Police". It is also possible to find photos that show the courtesy or even servile gestures of Polish policemen in relation to their German supervisors. However, the publication of this photograph alongside with the categorically sounding description shows how nonchalantly the author approaches the choice of sources. At such moments the reader wonders whether the book they are reading is really a reliable scientific work or a commentary tailored to the needs of a specific thesis.

The myth of Polish independence

Trying to demonstrate the alleged Polish independence in the General Government (enabling voluntary complicity tothe crime), the author repeatedly points to the direct interference of the Germans in the principles of performing police service, the imposing of disciplinary penalties, and visits and training conducted by the occupation authorities. This inconsistency of Grabowski's narrative deepens as the description of events develops.

Finally, referring to the "infamous Schutzmannschaft Battalion 202"[iv], the author failed to add that already in the early spring of 1943 the same battalion, sent to Belarus, was disarmed by the Germans, as part of its staff planned to flee and join the partisans. Reformed and sent to Volhynia, in the summer of 1943 it participated in the defense of the Polish population during the Volhynia slaughter. Later, a large part of its officers deserted and joined the ranks of the 27th Infantry Division of the Home Army.

Analyzing the individual cases of the police involvement in the mechanism of the gradual trapping and enslaving of the Jewish population (1939–1941), the author indicates how many cases in the field of administrative law (e.g. evading the wearing armbands with the Star of David) were recorded by the police composed of Poles. This is, of course, a serious allegation. Nevertheless ̶ in no part of the book does Grabowski indicate what the real scale of the phenomenon was in relation to the cases recorded the police files. Only by comparing these two numbers would it be possible to assess the scale of police involvement in the German occupation system. We also do not know in how many cases the police could not react differently ̶ they were in a crowd of people and they were not sure about if somebody was going to report them or not, or a German military policeman was standing nearby, etc. Conformity and fear are obviously a bad excuse. However, requiring everyone to show absolute heroism is equally absurd.

The same applies to the description of open ghettos, such as in Opoczno. According to the author, "an invisible but very effective surveillance ring"[v], forming the Polnische Polizei outposts, significantly hindered or prevented the Jews from escaping and hiding on the so-called Aryan side. Unfortunately, Grabowski does not resolve such issues as where the Jews would flee (to hide, while ensuring all survival needs), or whether the police forces in Opoczno (because their numbers were not given) were able to realistically control traffic between the Jewish quarter and the Aryan part of the city. At the same time, the author himself emphasizes that there was a 10-person German military police station next to the ”Blue Police” station in Opoczno. How true is the thesis that there was no supervision? Readers should answer this question themselves.

The author uses a similar procedure when writing about the camp in Morda in Mazovia. According to Grabowski, the Polnische Polizei was to train the guards of this facility, and they were to be recruited from among volunteers for this formation, who, in return, were directed to guard the camp with the Jewish population. The situation was alike for volunteers to the police who were in the ranks of Schutzmannschaft Battalion 202 (by the way, never belonging to the so-called Polish police formations and not part of the Polish Police in the General Government). However, here too, there is an error that cannot be detected by a person who is not aware of the history of police formations ̶ both the decision to create the battalion and the way of transferring candidates for service in it was not the responsibility of the Polish police authorities, who faced a fait accompli ̶ first demanding volunteers, and then forcing people to transfer people (both volunteers for service and staff). The fact that the training in this battalion was carried out by Polish policemen does not prove anything, because they were delegated at the request of the German police authorities. The Polish commanders could not oppose them.

In all the descriptions we can find information about German participation or complicity to crimes, such as in the description of the crime of the guardian Matusiak from Łochów. Of course, conformity, as I have already mentioned, cannot be any excuse for murderers. However, the basic question arises: are we dealing with voluntary and optional activity as part of an independent formation ̶ as the author wants it ̶ or rather with units reduced to the role of executioners as part of the occupant's dependent service, subjected to strict supervision and constant control? In addition, what was the real scale of the phenomenon in relation to the number of policemen? This question is hardly answered in Grabowski's work. If e.g. the source giving an idea of the scale of the crime is to be the amount of ammunition used, then the obvious question arises about the effectiveness of the firing. After all, not every fired bullet kills. Moreover (as the author himself admits) the police committed various small scams with the ammunition used, wanting to acquire additional bullets for trade or hunting.

It is a pity that the author omitted those issues which seem to contradict his theses. Quoting the diaries of the Cracow policeman Franciszek Banas (who cannot be omitted because he was awarded the title of the Righteous Among the Nations), Grabowski omits the entire thread Banas described of the referring several pre-war policemen to ghetto posts by Maj. Ludwik Drożański ̶ the pre-war commander of the city, and the deputy commander of the Cracow police during the war, Maj. Franciszek Erhardt (he also mentions the arrest of both officers, providing, citing Banas, an incorrect date that can be verified quite easily on the basis of the available sources). What's more, in the case of the descriptions of help for Jews by the police in Cracow, it is limited to the "brave Viennese" Oswald Bousko ̶ the Wachtmeiste of the German police. Instead, he forgets Wojciech Fick, mentioned by Banas, who, alongside with Banas, directed Maj. Drożański to the ghetto, and paid with his life for his involvement in saving Jews.

Perhaps the lack of mentioning of this issue is due to the fact that Fick's name appears on the obelisk dedicated to the murdered Polish policemen ̶ soldiers of the Underground, located in KL Plaszow, where some of them were killed. The author writes about this commemoration as follows: "Let us return to the monument to the heroic ‘Blue Police’. The obelisk could have been placed in front of the police station in Cracow. It could have been placed in front of any of over one hundred and twenty Cracow churches. It was, however, placed in the concentration camp in Płaszów, a place where some of the honored policemen were shot by the Germans. A place that ̶ so far ̶ was identified primarily (if not exclusively) with the martyrdom of the victims of the Holocaust, with ten thousand Jews who died in the Płaszów camp. Placing a monument there is a symbolic gesture that as much pays homage to the killed policemen as "re-indicates" the area of the camp for the needs of Polish martyrdom"[vi]. Apparently, something as elementary as commemorating a symbolic gravestone of people whose bones do not have their burial place and who cannot be visited by relatives in a cemetery, does not fit into his worldview with regard to non-Jewish victims.

Unfortunately, this passus well reflects the nature of the entire book, in which the worse the allegations against the police, the truer they are in the author's opinion. This is accompanied by half-truths. For example, Major Franciszek Przymusiński is only a career-man for Grabowski, a former Prussian officer wiping the floor with the Germans. There is no word about his testimony made during the Warsaw Uprising before the Home Army intelligence (in which he reported, among others, about his cooperation with the State Security Corps), nor about cooperation with the Union of Armed Struggle/Home Army (ZWZ/AK) intelligence. Lieutenant Colonel Marian Kozielewski was, in turn, presented as mediocre and eager for promotion. The author fails to mention that he greatly helped his brother Jan Karski (Jan Kozielewski) in preparing the famous report on the situation in occupied Poland (this can be seen especially in the first version of this document), nor that from the very beginning of the occupation he created underground structures in the police (included in this version of the report as the "Reinsurance POL" Company).

Confusion of executioners and victims

In his work, Grabowski gives many examples of crimes committed by Polish policemen on the territory of the General Government. Undoubted and true. However, both the historical context and the scale of these crimes are blurred by him or even obscured. This is not about relativizing crimes ̶ murders will always remain hideous acts deserving condemnation. However, putting forward the thesis that, in principle, the police corps was a voluntary and willing partner in the Holocaust, should be proven, also in statistical terms. However, we will not find anything in this paper. In return, we are forced to accept the uniqueness of only one victim and one threat. According to the author's words: "Can you suggest that the fate of Poles and Jews under occupation was similar, and that the threats faced by both nations were comparable? I hope that the readers of this book agree that such comparisons are completely unauthorized. Putting murderers and their Jewish victims on one scale is a form of falsifying the history of the Holocaust, called the Holocaust equivalence[vii] by Holocaust researchers.”

In this way Poles, a nation so badly hit during the war, are placed by Jan Grabowski in the same row with the swastika-wearing murderers.

Michał Chlipała

Photo: Katarzyna Kozioł and her sister Józefa Chłoń give a treat to navy-blue police officers, Otfinów, 1942/1943. Photo: Stanisław Chłoń. Source: Renata Guzera’s archive

Michał Chlipała (born 1981) – a lawyer and historian, employee of the Department of History of Medicine at the Collegium Medicum of the Jagiellonian University. Vice President of the State Police Remembrance Foundation of the Second Republic of Poland. Co-author of the book: (with Krzysztof Musielak and Jacek Walaszczyk) Kompanie rezerwy Policji Państwowej [State Police Reserve Companies] (2018) and others.

[i] K. Mięsowicz, Moje wspomnienia – tom IV [My memories – vol. IV], [in:] Dzieje Podkarpacia, vol. VI: Pamiętniki i wspomnienia, ed. J. Gancarski, Krosno 2002, pp. 93–113.

[ii] J. Grabowski, chapter I, subsection: Powstanie policji granatowej, czyli Polnische Polizei des Generalgouvernements [Establishment of the Blue Police, or Polnische Polizei des Generalgouvernements], [in:] idem, Na posterunku… [At the station]

[iii] Ibid, subsection German supervision.

[iv] Ibid, subsection Training and recruitment.

[v] Ibid, chapter II, subsection Police supervision in smaller centers: Opoczno.

[vi] Ibid., Ending, subsection Memory.

[vii] Ibidem.