The latter were easily distinguishable thanks to their souther beauty and words spoken in the melodious language of Dante and Petrarca. They were accompanied by groups of excited children, eager to get on a cruise on a big ship.

Thus, the epos of the soldiers of the 2nd Polish Corps, who tied themselves with Italian girls during their time on the Apennine Peninsula, was coming to an end. The ship pulled its anchor up and took course west towards the Gibraltar Strait. After it past it, it turned south - its destination was Buenos Aires, the capital of Argentina.

Soldiers-wanderers

The beginning of this extraordinary story goes back to 1939, when Poland wound up under the German and Soviet occupations. The tragedy of war did not, however, mean the eradication of the Polish state. It continued to exist, in exile, along the allied France and Great Britain. Already in 1940, the Polish army counting more than 70 thousand people was created in France. In May, 1945, when war ended in Europe, the Polish Armed Forces counted approximately 194 thousand soldiers. They were stationed in many countries at the time: in Italy, the Middle East, Great Britain, France and Germany.

The several years spent abroad by thousands of young men had to inevitably lead to Polish soldiers starting relationship with the women of the countries they were stationed in. Some of them turned to long-term relationships, marriages. Polish soldiers wed the most with Italians and the British, mainly Scots.

They were easily liked

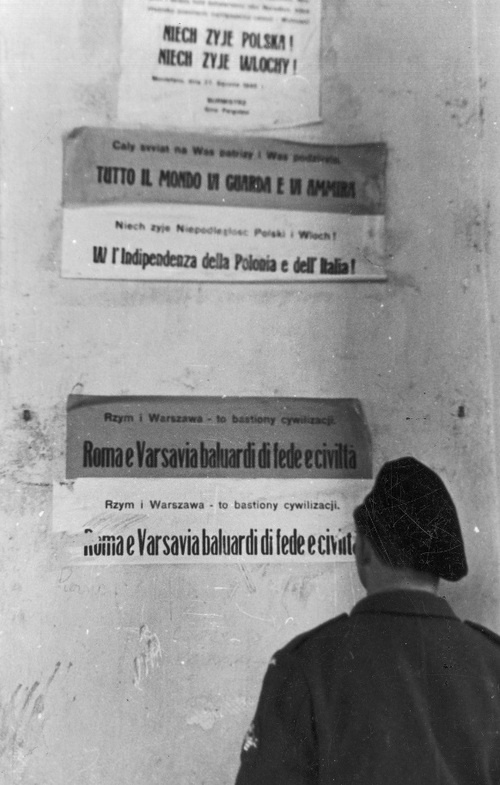

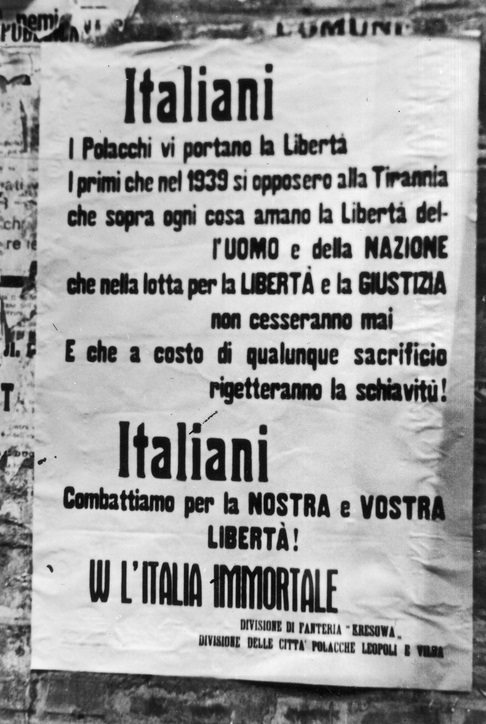

The victorious soldiers of the 2nd Polish Corps stationed in Italy in 1944-1946 were very popular among the female population of sunny Italia. It is also worth noting that Polish soldiers behaved well in Italy and were easily liked by the citizens of local towns and villages. It was commonly believed that:

“It was the atmosphere of friendship and kindness that made the Polish soldiers find their first loves in Italy and get married with Italian women.”

UK only for singles?

The war ended, but the fate of the 2nd Corps was uncertain. Many soldiers from the Eastern Borderlands did not want to return to communist-ruled Poland, so it was decided that they were to go to Great Britain, where they were to be demobilised.

The British authorities, however, did not want the soldiers of the 2nd Polish Corps to arrive with their wives, which was understandable as there were little jobs and apartments in Britain even for the English soldiers returning from duty. Under these circumstances, the married soldiers and their wives had to stay in Italy. According to the data from the beginning of 1947, 1,400 Polish soldiers stayed in Italy with their Italian wives. The number of Italian women, wives of Polish soldiers staying in that country, was higher than that and reached 1,800.

Camps for marriages

400 Polish husbands were already in Great Britain at the time and helplessly tried to reconnect with their wives. General Władysław Anders - the commander of the 2nd Polish Corps - with the order from 13 October, 1946, created the Group of Placement Camps in Italy, specially for the married soldiers. Six camps were established with living quarters for two thousand families. The soldiers of the 2nd Corps and their wives staying in the camps were taken care of, but they were in a situation far from ideal. The signing of the peace treaty with Italy meant that the Allied forces had to leave the Apennine Peninsula in 90 days. There were fears that Italian authorities, under pressure from the authorities of the People’s Poland and Polish communists, would want to get rid of of Poles as quickly as they could and possibly even deport them east.

Between the British and De Gasperi

In January 1947, the British ambassador to Rome, Sir Noel Charles, wrote an official letter to the Italian government where he presented the stance of the British government on the problem of Polish soldiers married to Italian women. He pointed out that most of the soldiers of the Polish Armed Forces did not wish to come back to their country in the political climate of the time. He argued that given the fact they took part in the joint Allied campaign, their future should be treated as an international, humanitarian matter. The British, not avoiding their participation in its completion, pointed out that Italians should partake as well, at least due to the fact that Poles substantially helped liberate Italy from the German occupation. Moreover, it was in the best interest of Italian citizens, the Polish soldiers’ wives.

The Italian government, led by Alcide De Gaspieri, was not, however, eager to demobilise the Polish troops in Italy. He feared the additional difficulties at the job market and the need to spend much of the state funds. Although he agreed that Poles could apply to stay in Italy, they had to prove that there were realistic possibilities for them to find employment which would allow them to provide for their families. The Italians’ attitude troubled ambassador Charles who, in the beginning of January, alarmed London that a forced demobilisation of Poles without the Italian government’s consent would cause huge complications, since the Italians could retaliate against the Poles. In his opinion, the Poles’ deportation to communist Poland had to be taken under consideration.

In London, however, the situation was not judged as pessimistically. First and foremost, the solution to the problem was to be found through emigrating the Polish-Italian marriages across the ocean, to Argentina. The initial talks on the subject led by the British diplomacy with Argentina had shown much promise. The perspective of mass emigration across the ocean also prompted the British government to send back the 400 former Polish soldiers to their wives in Italy.

Indeed, concrete steps were taken at the international forum to move forward with the emigration of Poles from Italy. Already in 1946, the ambassador of the Polish government-in-exile (in London), Mirosław Arciszewski, worked on this project vigorously. He had very good contacts among the Argentinean generals, including the circles of Colonel Juan Peron, the rising star of the Argentinean politics. He presented the plan of emigration of the Polish soldiers of the 2nd Corps to Argentina. His proposals were met with a positive response not only from the military circles, but also from Dr. Ramon Peralto, the head of emigration office in Buenos Aires. Already in the middle of January 1947, it was announced that a special Argentinean mission was to arrive in Europe. It was first to arrive in London, where the emigration of Polish soldiers would be discussed with the British.

In the end of January 1947, ambassador Charles informed London that after talks with the Italian ministry of interior there was a chance to find an agreement with the Italian government on the demobilisation of the soldiers of the 2nd Polish Corps married to Italian women. The Italian government was to give the right of permanent residence to those Poles (group A) who could prove that they had enough funds or chances for employment to provide for themselves. The rest, the so-called group B, were to receive the right for temporary residence for several months. In return to these concessions, the Italian government demanded a guarantee from the British government that its diplomacy would follow through with the emigration of the Poles from group B. Although the British government could not give “firm” guarantees to the Italians that other countries would accept the Polish-Italian marriages, Rome was ready to accept the promises that London would do everything in its power to make the emigration come to fruition.

To the country of the beautiful Evita

The country which accepted the biggest number of the soldiers of the 2nd Polish Corps, married to Italian women, was Argentina. This solution was especially beneficial to them, since that country had a strong economy at the time and it was relatively easy to find employment there. The fact that there were large Polish and Italian diasporas in Argentina was also a favourable circumstance as the new emigrants could count on their support. In the beginning of 1947, the representative of General Juan Peron’s government came to Europe ready to agree to the arrival of the emigrants from the Old Continent. Following his stay in Italy and talks in London he announced that Argentina would accept 2,000 Polish soldiers with their families. María Eva Duarte de Perón, the wife of the Argentinean leader, confirmed this commitment during her travels in Europe during which she also went to Italy. To this day, among the Polish emigrants, there is a conviction that if not for the personal appeals of the famous Evita, they would never be invited to Argentina. There could be some truth to it, since Peron’s wife was famous for her engagement in charities for the poor and those in need. That is why this woman was so loved and admired around the world.

The implementation of the plans of emigration of the Polish-Italian families was quick and efficient. Already in July 1947, the first transport of 600 people left from Genoa on the Empire Halberd ship. The next group of former soldiers of the 2nd Polish Corps and their families (302 men, 302 women and 105 children, in total 709 people) sailed from Buenos Aires on September 12, 1947. The third transport left on September 24 and took aboard 625 Poles. More transports followed soon.

In total, the emigration to Argentina included 5,000 people, Polish soldiers and their families. Argentina accepted the biggest number of Poles from all the countries of South America. In total, between 1945-1951, 12,000 Poles went to live there.