The defeat of Germany in World War I was a triumph of an alliance of five superpowers; Great Britain, France, the United States, Italy and Japan. When the conference that would prepare peace with Germany was ceremonially opened on 18 January 1919 at the headquarters of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Paris, the leaders of the European Powers – British Prime Minister Lloyd George, French Prime Minister Clemenceau and Italian Prime Minister Orlando – knew that this time, Europe’s borders would not be drawn arbitrarily, but in accordance with the new vision of a world order brought from overseas by American President Woodrow Wilson. Even during World War I, the American leader said that the new peace must be based not on harming the defeated side, but on justice and law. Thus, he presented these conditions for a future peace in Europe at a session of the combined houses of Congress on 8 January 1918. European politicians in allied countries, eagerly waiting for the Americans to join the war, did not attempt to explain the complexity of the historical and ethnic situation, especially in Central and Eastern Europe.

Ultimately, the solutions adopted in the Treaty of Versailles were the result of two tendencies. The first of these was the American president’s desire for the emergence of small and medium-sized nation states, whose sovereignty, according to the principle of self-determination, would be guaranteed by a collective security system (the League of Nations). However, it is also easy to see in the treaty the effects of the British desire to maintain the traditional balance of power on the continent, and thus to limit the weakening of Germany, contrary to French hopes. Lloyd George made a concession only in the case of Alsace-Lorraine, accepting the annexation of these provinces to France, which had already been announced by Marshal Foch in 1918.

The plebiscites were only a small part of the Versailles Treaty’s vision of the European post-war order. They were conducted in relatively small territories, where the pre-war borders definitely did not correspond to ethnic divisions, and where the superpowers could not come to an agreement on an arbitrary drawing of the new border.

The adoption of the principle of a vote by the entire population was thus not a common solution, but an exception. It was not a question of eliminating multi-ethnic and multicultural regions; people were aware that, because of the plebiscites, questions of rights for many national and cultural minorities, important to Europe’s future, would emerge. Nevertheless, the vote was intended to give the superpowers an excuse to make decisions where they could not find a shared solution through compromise. Plebiscites were to be held in the following areas bordering Germany:

- on the border with Belgium, in the municipalities of Eupen and Malmedy (after the vote in 1925, this territory was annexed into the Kingdom of Belgium; both municipalities have a significant German minority to this day);

- on the border with France, in the Territory of the Saar Basin, a plebiscite was announced after 15 years of a League of Nations protectorate (shortly after Hitler came to power, in a 1935 vote, a vast majority of the inhabitants voted in favour of a return to Germany);

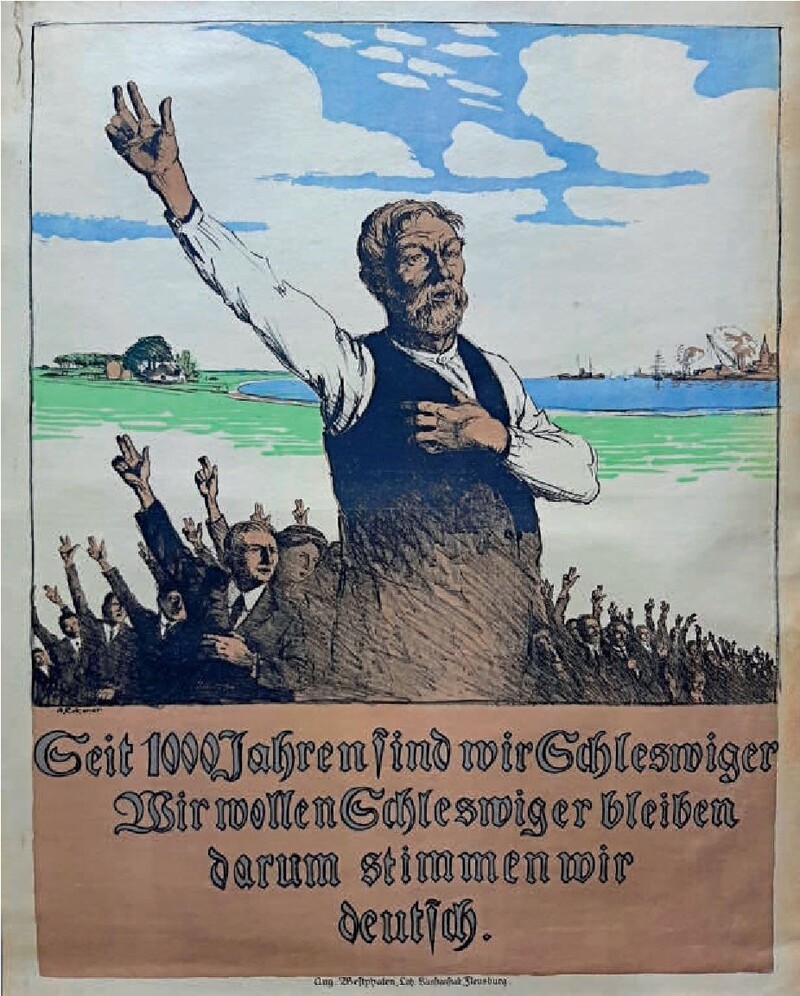

- on the border with Denmark, in Schleswig, a 1920 plebiscite divided the region into the northern part, where the majority voted in favour of Denmark, and, more to the south, Central Schleswig, where the Germans were successful;

- on the Polish-German border, plebiscites concerning the border questions were to take place in: 1. Warmia, Masuria and Powiśle (the vote was held on 11 July 1920 and the majority voted for annexation to Germany; Poland was granted only a few municipalities in Powiśle and Masuria, while the national border was drawn along the east shore of the Vistula); 2. Upper Silesia, where the plebiscite was not held until 1921, and where the eastern part of the plebiscite area was granted to Poland only after the Third Silesian Uprising, after negotiations were renewed in Paris and the League of Nations announced the decision of the superpowers.

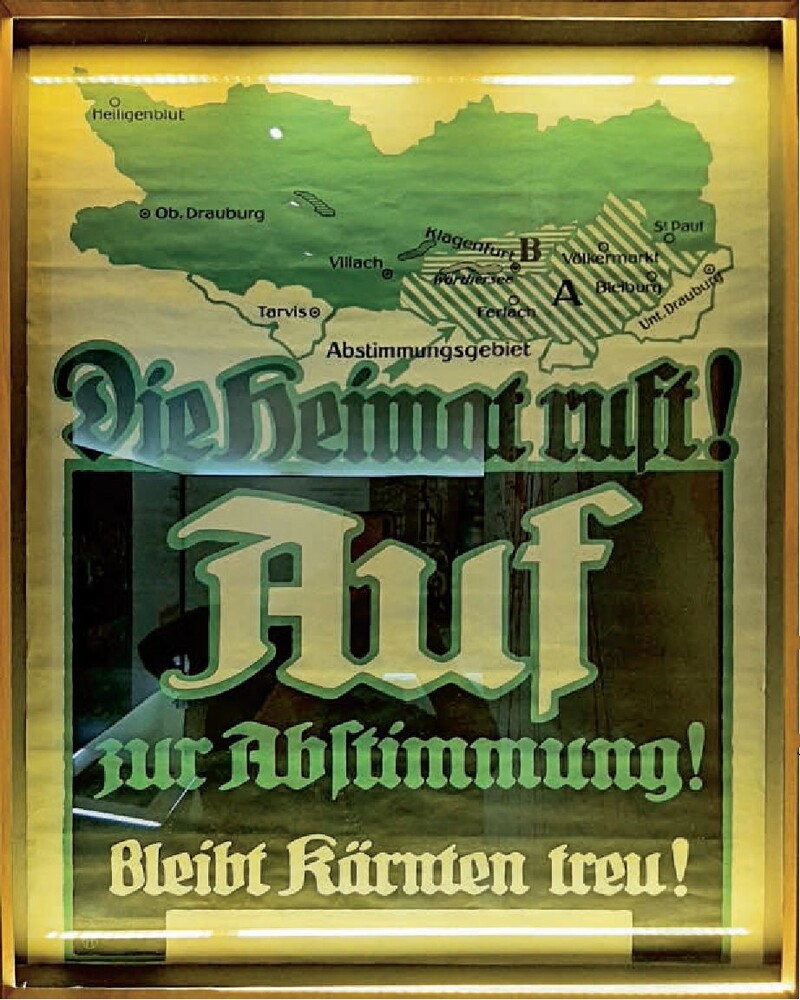

The principle of settling disputed issues in certain border areas, adopted in Versailles for the German borders, were also extended to some border areas of the former Austro-Hungarian empire after the signing of peace treaties with Austria and Hungary. On this basis, plebiscites were held:

- on the Austrian-Yugoslav border in southern Carinthia in 1920 (60% of votes for Austria);

- on the Austrian-Hungarian border in Sopron (German: Ödenburg) in 1921 (more than 65% of votes for Hungary);

- on the Polish-Czechoslovak border, plebiscites were also to take place (in Cieszyn Silesia, Spiš and Orava), but ultimately they were not held; Poland, threatened by the Soviet offensive, agreed to an arbitration by the superpowers in 1920 and, as a result, to an unfavourable division of the disputed territory.

The idea of holding plebiscites in various border areas, proposed at the Peace Conference in Paris, and later also used to determine the new Austrian border, seems fair and noble today, if we are unaware of its historical context. The people themselves were to decide what country they wanted to be part of. Unfortunately, as it turned out, the results of the vote did not solve political problems, much less the ethnic and cultural differences. In most of the territories where plebiscites were held, despite the borders being set out according to their results, political conflicts did not end. After World War II, the idea of the plebiscites was not taken up again. The shape of the borders in Central and Eastern Europe was determined by leaders of the victorious superpowers at international conferences. Their guarantor was to be a new international organisation (the UN), which this time included the United States.