Dritte Verordnung über Aufenthaltsbeschränkungen im Generalgouvernement – the Third Regulation on Residence Restrictions in the General Government – imposed the death penalty on Jews who left their designated districts of residence without authorisation and on those who would consciously provide a Jew with a hiding place.

That is how Izajasz Leszcz described contacts of Jews with Poles in the Radom ghetto in 1941 after the war:

‘Officially we were given 15 decagrams of bread, some sugar and salt. A lot was smuggled in. Jews worked in tanneries, at various Jewish outposts. In the brickyard, where I was a clerk, there were 20-30 workers. On the way home [from the ghetto], products were brought in. (...) Not everyone knew how to smuggle’.

Under various circumstances and in defiance of German prohibitions, many other people established relations with the so-called ‘Aryan side’ and had such experiences during the German occupation. It greatly facilitated their survival in the tough ghetto conditions. According to scholars, at various times, there were about 400 so-called ‘Jewish quarters’ and ghettos in the General Government, which Jews were not allowed to leave. The first of these was established as early as October 1939 in Piotrków Trybunalski.

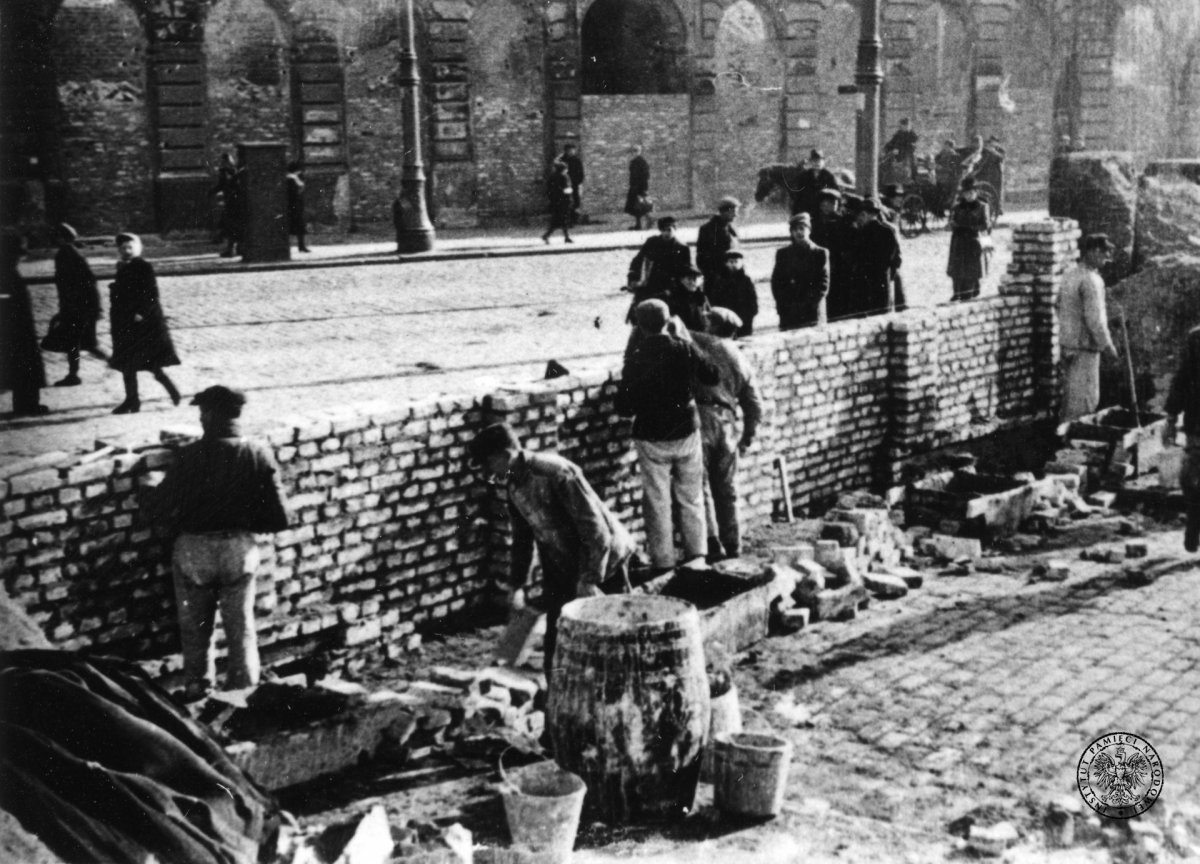

Forced ghettoisation – the path of indirect extermination

The appearance of ghettos was connected to the German policy aimed at isolating the Jewish population from the outside world. It was easier for the Germans to carry out indirect extermination there. A significant obstacle proved to be Polish-Jewish contacts, especially commercial ones, which both sides - Jewish and Polish – maintained. The German authorities tried to break these relations while at the same time constantly deepening antagonisms between Poles and Jews in various ways according to the principle divide et impera. We can read about this, for example, in official prints of the NSDAP's Office of Racial Policy. The authors of one of them stated, among other things, that

‘The German administration will be tasked to divide and set Poles and Jews against each other.’

Helping escapees – an act of heroism

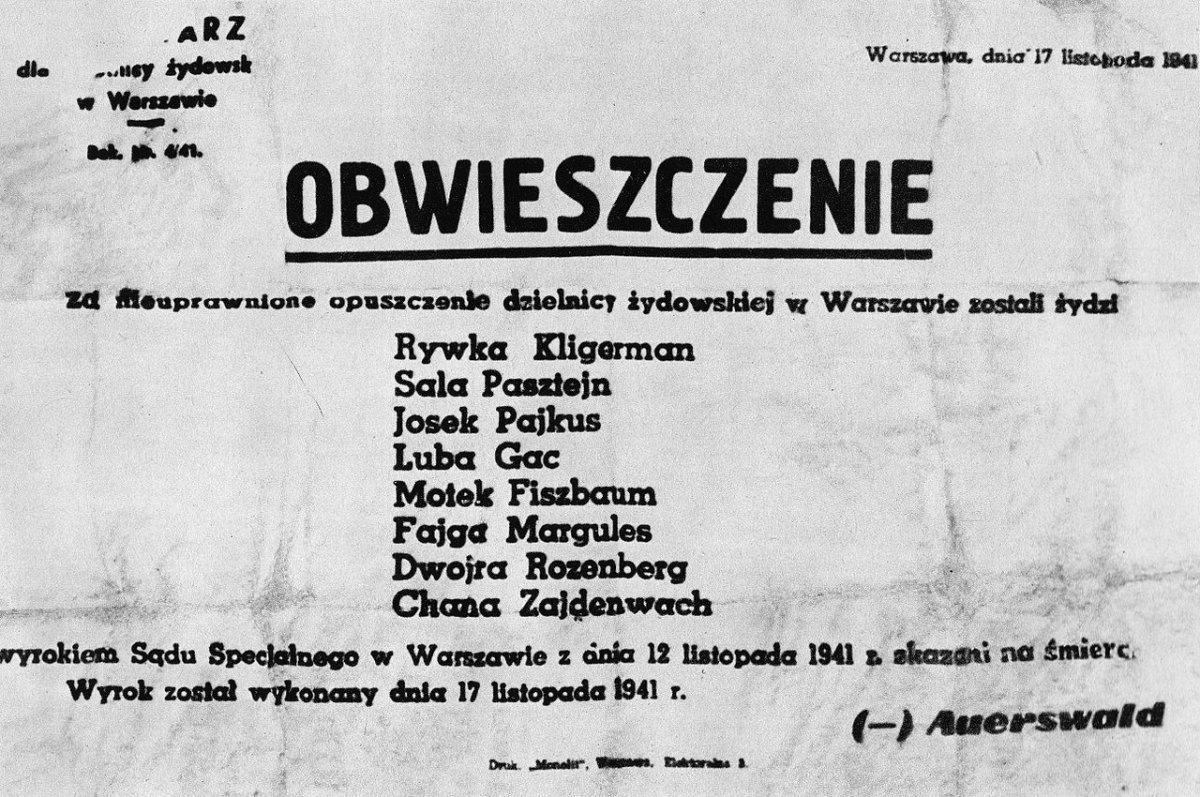

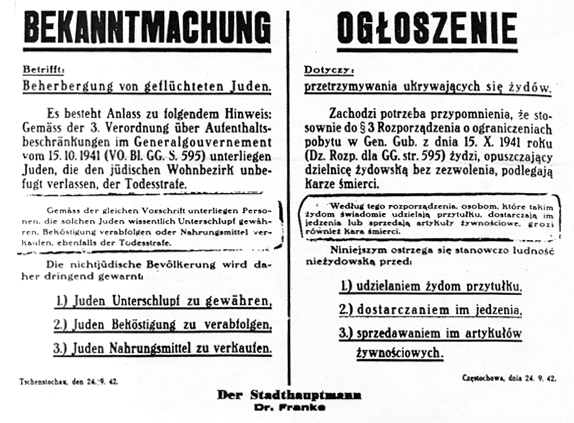

The key legal act with the force of a decree, aiming to break Polish-Jewish contacts, was the Decree of Governor-General Hans Frank of 15 October 1941. In one act, there appeared the threat of the death penalty both for leaving the ghetto by a Jew and for giving a Jew shelter outside its borders:

‘Jews who leave their assigned district without authorisation are subject to the death penalty. Persons who consciously provide such Jews with a hiding place are subject to the same punishment.’

The Decree also reads:

‘Abettors and helpers shall be subject to the same punishment as the perpetrator, an attempted act shall be punished as an accomplished act. In milder cases, heavy imprisonment or prison may be imposed.’

The death penalty was in force both in the General Government and in the Polish parts of the Reichskommissariat Ukraine and the Reichskommissariat Ost (the regions of Volhynia, Polesie, Novogrudok, eastern Bialystok, and Vilnius). However, no such decree was formally issued in those areas.

The ineffectiveness of the act – towards stricter sanctions

Whether the law mentioned above was effective is a separate issue. In the case of the Jewish population, it seems that it did not have a sufficient deterrent character. Since Jews in the ghettos suffered significant deprivation and hunger and were subsequently physically destroyed, they had to maintain contact with the outside world at all costs. As far as Poles are concerned, the answer to that question must be sought in later German actions. Some scholars assume that the willingness for maintaining contacts with the inhabitants of the ghettos, including aid from the Polish side, was still so noticeable to the Germans – and interfered with the process of exterminating Jews – that they decided to treat Poles even more harshly by extending criminal sanctions (the death penalty) to their families or acquaintances from the autumn of 1942. From then on, the threat of the death penalty loomed over anyone who knew about the help given to Jews. Moreover, all forms of help began to be punished, not only those giving shelter to the Jewish population as in the legal act in question.

As for the Decree of 15 October, it is worth noting that none of the law functions appeared in its positive form in the General Government legislation. In this case, as many as three of its adverse functions are concentrated: outrageously repressive (public terror), segregative, and eliminative. The cruel law of the General Government is a remarkable historical experience that must be remembered in the context of Polish-Jewish relations.

Alicja Gontarek