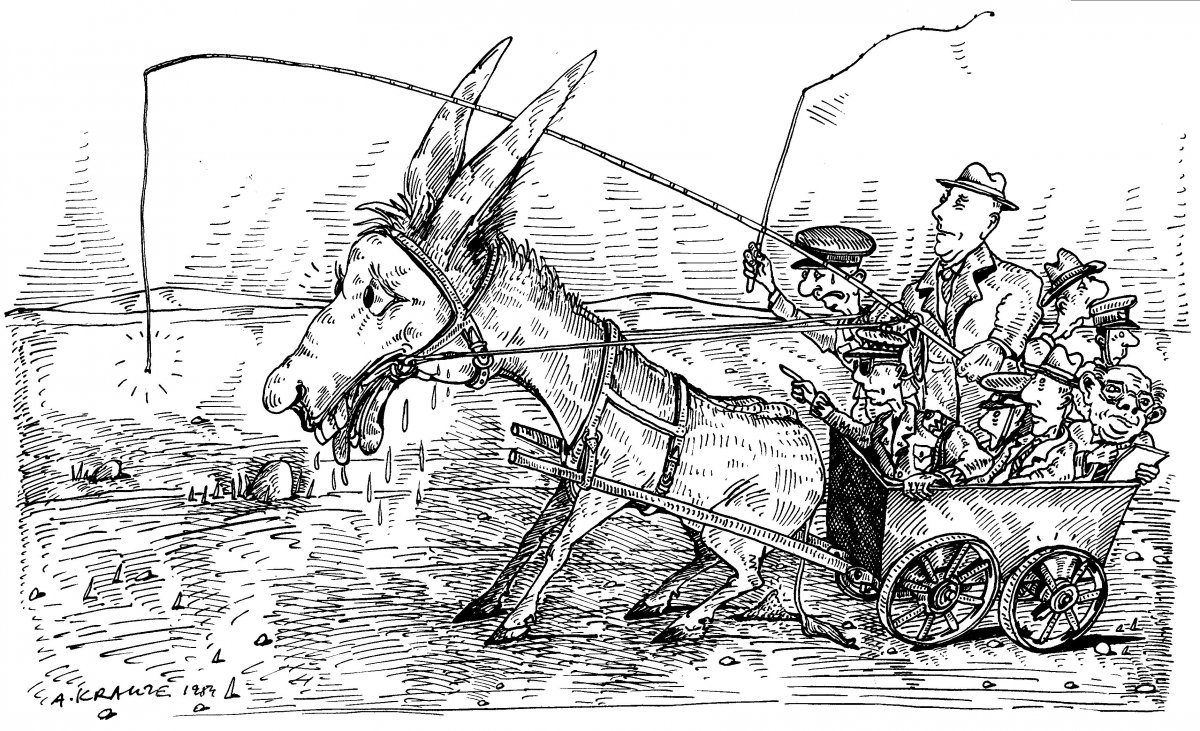

The fact that the grand ‘Solidarity’ movement also encompassed farmers’ ‘Solidarity’ which united inhabitants of the countryside, is frequently omitted. The communists were very determined to ban the legalisation of the peasant union, and when that failed, they hindered its operations. Despite this, its ranks united a great number of people. For the first time since the period of activity of the Polish People’s Party (Pl. PSL) of Stanisław Mikołajczyk, the peasants massively opposed the communist regime.

The beginnings of the independent, peasant union movement can be traced back to September 1980. However, in order to comprehend its origins, one needs to reach back several years earlier. After the Sejm of Poland passed the pension act of 1977, which was unfavourable to farmers, and after the independence of farmers’ circles was denied, peasant self-defence committees began to be established in 1978, in the following regions: Lublin, Grójec, and Rzeszów. Furthermore, the provisional committee of the independent farmers’ trade union in Lisów (Pl. Tymczasowy Komitet Niezależnego Związku Zawodowego Rolników w Lisowie) and the self-defence committee of the faithful in Podlasie (Pl. Podlaski Komitet Samoobrony Ludzi Wierzących), were also established. These were the first rural organisations in the People’s Republic of Poland that were independent, were not acknowledged by the government, and which openly operated outside of government control. This was, among others, the effect of the contact between rural inhabitants with the Workers’ Defence Committee (Pl. KOR, later renamed the KSS KOR) and the Movement for Defence of Human and Civic Rights (Pl. Ruch Obrony Praw Człowieka i Obywatela). All of this was accompanied by the peasants’ awareness that they are supported by local priests, who not only aided them, but also enormously influenced their creation and operation. Beginning in 1997, independent press for farmers started to be published, among others, in Gospodarz (The Host, variously Farmer), Postęp (Progress), and later Placówka (En. Outpost) and Rolnik Niezależny (The Independent Farmer).[1]

At the turn of the 1970s, some areas also saw other, loose and informal opposition circles related to the popular movement, which, however, did not operate openly. They were mainly collections of former activists of the Polish People’s Party of Stanisław Mikołajczyk. In their circles, they observed and commented on events in the country, in particular those that applied to the policy of the government towards the countryside and farmers. As former members of the Polish People’s Party, who did not consent to cooperate with communists and did not transition to the Stalinist satellite United People’s Party (Pl. ZSL), they were pursued by the Polish security service. In Kraków, Stanisław Mierzwa was the focus of particular attention. Reports on him stated: ‘[…] through trusted persons he tries to be up to date on the atmosphere among peasants and the economic situations. He recommends that operatives continue to penetrate to the individual villages, in order to draw the right conclusions, which, in the future, might form the basis for specific political actions.[2]’ Some former members of the Polish People’s Party were distressed about the influence of the KSS KOR and other circles on the peasant committees, in particular that of Adam Michnik, Jacek Kuroń, but Leszek Moczulski as well. In Warsaw in 1979, the Centre for Popular Thought [Pl. Ośrodek Myśli Ludowej] came into being, made up chiefly of former members of the People’s Front [Pl. SL], the ROCh party, the PSL and then the ZSL, and the seniors’ club of the popular movement (Pl. Klub Seniorów Ruchu Ludowego) operating under its auspices, who were expelled from the front due to open criticism of the farming policy of the state.

Solidary farmers

When the strikes broke out in Pomerania in August 1980, soon, the ranks of the Inter-Enterprise Strike Committee (Pl. Międzyzakładowy Komitet Strajkowy), formed in the Gdańsk shipyard, were joined by representatives of local peasants. Henryk Bąk cooperated with them; he co-organised the first independent peasant trade union created in 1978 in Lisów. After the August Agreement was signed, September 1980 saw the creation of further organisational committees of peasant trade unions in various parts of Poland.

Already on September 7, 1980, independent peasant activists from various parts of the country met up in Warsaw and decided on the establishment of an independent self-governing farmers’ trade union. A further meeting, on September 21 at the seat of Warsaw’s Catholic Intelligence Club, saw representatives of more than a dozen voivodeships meet. Despite differing views on the future union, and despite disputes – whether it should be just a union of peasants, or whether it should also encompass employees of social farming and other rural inhabitants – a new, extended all-Polish formation committee of the independent self-governing farmers’ trade union could be called into existence. It was made up of 42 people. The bylaws of the union were drawn up immediately, and it was ultimately called the independent self-governing farmers’ trade union ‘Rural Solidarity’ [Solidarność Wiejska]. For the purpose of registration, its documents were submitted to the voivodeship court in Warsaw on September 24, 1980, by the first, provisional chairman, Zdzisław Ostatek. At that time, a motion was also filed by the independent self-governing trade union ‘Solidarity’ [Solidarność]. Soon, a further group of peasant unionists became active, which in November 1980 announced the creation of the federative domestic council of peasant Solidarity. An agricultural producers’ union was also established.

Soon after the motion for registration was submitted, the ‘Rural Solidarity’ began its organisational work across the entire country. The movement enjoyed great trust of the church hierarchy – even greater than ‘Solidarity’ had – in particular by the Primate of the Millennium, Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński. This support was reflected among certain priests, e. g., in Niegardów, by the initiative of Father Marian Gołąbek, in October 1980 a group of priests wrote an open letter to priests caring for farmers – in which they voiced their decisive support for the establishment of ‘Rural Solidarity’: ‘If we neglect this voice of God speaking through the people – then history will accuse us of the sin of neglect, and this would have certainly not been culpa levissima, the least guilt, from the point of view of social ethics – for abandoning those whom we are supposed to lead, walking side by side with them. […] May it not turn out that the sheep overtook the shepherd, that we are behind. […] We say this specifically: friendly care of the rural priest should be expressed, e. g., in making a hall available for parishioner meetings or in explaining the situation and the emerging possibilities. Farmers need to be taught about the method of establishment of farmers’ unions outside of the framework of political organisations or the state administration. These must be entirely independent unions! It is necessary to make the parishioners knowledgeable about the joint farming laws already approved for all of Poland’[3].

Despite the fact that the voivodeship court in Warsaw denied the registration of the peasant union already on October 29, 1980, for the first time, stating that individual farmers are not entitled to the right of unionisation, organising work continued across the entire country.

A meeting of representatives of farmers and rural unionists from all of southern Poland took place on December 7, 1980. The leaflet encouraging everyone managing land to participate in this ‘little parliament’ included, beside the information about the meeting itself, the words of the call of Edward Małecki, a farmer from Korabiewice in the Skierniewice voivodeship, illustrating the attitude of the government towards peasants. Treatment as second -classcitizens was expressed inter alia in the lack of production resources, harsh treatment by officials, inadequate provisions in the food ration stamps. The leaflet also included encouragement for the establishment of rural unions: ‘Workers undertook a struggle not only for increased pay and Saturdays off or other interests of theirs. They commenced it to finally bring some kind of order to our country, so that the Polish nation could live just like other nations do – with pride and wealth. The people of the “Solidarity” trade union were blessed by the Holy Father, John Paul II. They have shown many times, how rationally they operate and how deeply thoughtful their every move is. And that is why they do not want to decide for us – they want the fate of the Polish peasant be decided by the peasant himself. Through organisation in an independent self-governing farmers’ trade union. WE FINALLY HAVE TO COMPREHEND THAT OUR FATE LIES IN OUR HANDS AND THAT NOBODY BUT US CAN TURN IT AROUND [original emphasis – M. Sz.].’[4]

From a session to a strike

During the first session of ‘Rural Solidarity’ in Warsaw, on December 14, 1980, 1200 participants represented peasants from all voivodeships. The delegates stated that almost a million people are members of the union in the country-wide. They discussed issues of registration of the union, unification with other peasant unions, namely with ‘Peasant Solidarity’ [Pl. Solidarność Chłopska] and with the self-governing union of agricultural producers. Also discussed was the situation of agriculture in Poland and the reasons hindering its development. A protest was sent to the Polish Sejm concerning the expansion of the holiday facilities of the Cabinet of Ministers in Arłamów, Muczne and Caryńskie, and against ‘socially dangerous’ press information concerning farmers.[5]

The days of late Autumn and Winter favoured the field organisation work of ‘Rural Solidarity’. The work of the union leaders focused on the development of structures, giving advice to farmers in terms of fighting injustice and the bad decisions of the administration authorities or the justice system. As Bronisław Łuczywo, head of ‘Rural Solidarity’ in the voivodeship of Kraków, stated: ‘We had […] the satisfaction that they never left us without having their affairs taken care of. And sometimes one of our people needed to provide information to 60-100 others’.[6] Thanks to this, the local, commune, and countryside structures were bolder in developing their attitudes towards local authorities.

A further denial of registration of the farmers’ union and lack of reaction to its demands coupled with misguided decisions of the authorities – e. g., the support for the compromised farmers’ circles and the announcement of introduction of rural local governance through them – were met with much negativity among peasants. The course of the congress of the ZSL, and lack of significant changes in the leadership of this party, was summarised similarly: ‘This only supports the conviction that ZSL, having done nothing for peasants for years, continues to be but a dependent satellite of the [Polish United Workers’] Party and will do nothing for peasants. It seems that this prevention of changes in the leadership of the ZSL, for fear that radicals might come to power, instead of aiding the agricultural policy of the Party, had completely blocked this communication channel with peasants. The lack of changes means that peasants cannot expect anything from the ZSL, and this is the way this is understood.’[7]

The general discontent, the clear indication of the lack of good will of the authorities, and at the same time, the increased awareness of the power behind the union-in-organisation, caused the local protests at Ustrzyki Dolne and Rzeszów to be transformed in a long-term and all-Poland strike. After the representatives of other regions of Poland formally entered the ranks of the strike committee on January 4, 1981, it was transformed into the All-Polish Strike Committee [Pl. Ogólnopolski Komitet Strajkowy].

In solidarity with others on strike, short strike actions and manifestations took place in various parts of the country. Already during the protest of Rzeszów, on February 10, 1981, Warsaw saw the second revision session before the Tribunal of Poland concerning the registration of ‘Rural Solidarity’. It saw thousands of farmers from across Poland meet. Even though the court once again denied the motion, it acknowledged the right of the farmers to unionise within the structures of a trade union, and it concluded that this registration will be possible after the Sejm passes suitable legal provisions. This (just like later strike actions and agreements) is one of the most important events in the history of the Polish countryside.

The effects of the all-Polish farmers’ protest were not only the signing of an accord with the government on February 18 and 20, but also the unification of the peasant union movement. Thanks to joint actions by diverse groups, integrating during protests at the seat of the voivodeship council of trade unions in Rzeszów and at the Tribunal building, the establishment of the National Negotiation Committee of the independent self-governing trade union of individual farmers ‘Solidarity’ was formed in Bydgoszcz on February 13, 1981. It was to convene a joint meeting of the delegates of farmers’ trade unions for the purpose of unification, planned for March 1981. At the same time, field work started on a further stage in the development of organisational forms, e. g., the establishment of voivodeship structures and their leadership, and elections of delegates for the unification meeting.

The Security Service against peasants

The development of the situation in ‘Rural Solidarity’ was closely followed by the Polish Security Service. Despite the intense destruction of its documentation concerning infiltration and disintegration of the peasant union, as perpetrated in 1989-1990, some documents remain that enable the reconstruction of its operations. The rural opposition was originally handled by Department III A of the voivodeship commands of the Militia. In March 1981, the central offices of the Security Service, due to aid by the Church structures in the organisation of ‘Rural Solidarity’, moved ‘coverage of the rural chapter’ to Department IV of the voivodeship commands of the Militia, where two new sections were developed – VII, which was to take care of the ‘base’ and coverage of the food complex, and VIII – controlling the ‘superstructure’ through combating of ‘anti-socialist activity’ in the countryside. Oversight from Warsaw was held among others by the Deputy of the Director of Department IV of the Polish Ministry of the Interior, Col. Zenon Płatek, and the head of Section VIII in Department IV of the Ministry, Col. Roman Potocki.

On December 22, 1980, Warsaw saw an advisory meeting of the heads of Department III A of the Security Service in the voivodeship commands of the Militia, concerning, among others, combating the brewing opposition in the countryside. The Deputy Director of Department IIIA of the Polish Ministry of the Interior, Col. Stefan Olejarz, wrote a letter on January 10, 1981 to the individual deputy voivodeship commanders for the Security Service, in which he bound the subordinate unions to create subject files bearing the code name ‘Rural Solidarity’. The initial analysis of the situation in the voivodeships was to be sent to Warsaw by February 1, 1981 at the latest. The analyses included descriptions of the beginnings of operations of ‘Rural Solidarity’ and listed and described its key activists. The objectives of the operation were most probably very similar across all Poland. In Kraków, the code name was ‘Rural Solidarity’ or ‘Melting Pot 2’ [Pl. Tygiel 2], and the task was: ‘full infiltration and information about the actual peasant unions and organisations that were created and that operate in the urban voivodeship of Kraków within ‘Rural Solidarity’, their objectives and tasks, the resources, the main inspirers and the key activists, peasant press, ties and inspirations of the inter-enterprise trade union ‘Solidarność Małopolska’; operational infiltration and combating against influence on the peasant movement by components and forces of anti-socialist provenance [being] under the influence of former activists of the Polish People’s Party and of reactionist Church members; undertaking operations and support for party instances and administrative authorities in the elimination from these unions of persons opposing the agricultural system of the People’s Republic of Poland, the policy of the party and the state for the countryside, and persons undertaking activity aimed against public order and security; documenting of facts of violation of legal norms in force by activists and members of ‘Rural Solidarity’, which could influence the removal from the picture of the main inspirers of the establishment of ‘Rural Solidarity’; coordination of operations with all sections of the Militia and the Security Service’.[8] A further task was to weaken the positions of particularly dangerous activists, and support for those whose attitude was rather that of compromise or those who were recruited [by the Security Service]. The plan was for people from the outside to be moved to operate in the union, who were secret operatives, e. g., journalists, who would disclose union operations, and, through their publications, would show the lack of reason for the establishment of ‘Rural Solidarity’. An additional tool was to be analysis of correspondence, wiretaps, and observation of meeting places.

March 1981 saw, by order of General Konrad Straszewski from Department IV of the Polish Ministry of the Interior, the development of the plan of preventive and warning discussions with delegates to the national meeting of ‘Rural Solidarity’ in Poznań on March 4th and 6th. The objective of the discussions was to discourage delegates (by persuasion or threats) to go to the meeting, as this is an ‘illegal’ meeting of an organisation without a court registration. During the first all-Polish meeting of delegates of independent self-governing trade unions of individual farmers in Poznań, which took place on March 8 and 9, 1981, the three peasant organisations were finally united. The bylaws, organisational structure and name of the union were approved. The highest-yet preliminary power of the independent trade union of individual farmers ‘Solidarity’ was to be the All-Polish Foundation Committee, headed by Jan Kułaj, a farmer from the voivodeship of Przemyśl.

During the second half of March and the first half of April of 1981, trade unions across all Poland followed the course of the strike in Bydgoszcz, initiated by the local voivodeship council of individual farmers. The demands were for the acknowledgement of individual farmers and a clear settlement of the role of farmers’ circles. Among others, Michał Bartoszcze and Jan Rulewski (who supported the strike as a representative of ‘Solidarity’) were beaten up. Peasants across all Poland were ready to provide food for the strike. However, an agreement could be signed, which declared the legal acknowledgement of the peasant union movement.

When ‘Rural Solidarity’ was finally registered on May 12, 1981, after months of struggle, quite normal operation could finally commence. The assumption was that individual circles will follow the policies of the local authorities in the following areas: exchange of peasant land for social economy; management of the State Land Fund; agricultural investments and provisions for agriculture, contracting and purchases, and services for agriculture. The basic role of a circle was to bring transparency to the decisions of commune authorities followed by their assessment and suggestions of possible changes and improvements, and in case of grave errors and abuse by the authorities, – resort to the legal route, repair of damages, and punishment of the guilty. Should these actions produce no effect, the possibility of the organisation of protests was indicated. The circles were also informed that within two months of registration, general assemblies of union members in the villages were to be called and leadership structures were to be selected. In the individual regions, drafts were made of the programme of development of agriculture and the food economy, which were meant to include suggestions of solutions in the area of loans for agriculture, the operation of agricultural services, technical services for agriculture, provisions of equipment and tools for production, education and culture in the countryside, and social and subsistence issues of the countryside as well as pricing and contracting policies.

Mateusz Szpytma, Ph.D.

[1] Literature concerning the operation of farmer ‘Solidarity’, especially in the years 1982-1989, is relatively limited. Until today, some of the key publications on the topic are: A. W. Kaczorowski, Geneza niezależnego chłopskiego ruchu społeczno-zawodowego (1976-1980), [in:] Z badań nad dziejami wsi w Polsce, ed. by Z. Hemmerling and M. Nadolski, Warszawa 1990; S. Dąbrowski, Solidarność Rolników Indywidualnych 1976-1981, Wrocław 1993. The majority of later literature was developed as part of the work of the Polish Institute of National Remembrance. The history of peasant opposition before August 1980 was chiefly described by M. Choma-Jusińska. Her most recent publication, Początki niezależnego ruchu chłopskiego 1978–1980, Lublin 2008, drawn up together with M. Krzysztofik, is an edition of sources provided with a preface. Descriptions of the operations of ‘Solidarity’ of individual farmers in various regions were published, among others, by T. Chinciński, A. Kura, M. Szpytma. A supraregional work is one by D. Iwaneczko, Opór społeczny a władza w Polsce południowo-wschodniej 1980-1989, Warszawa 2005. Interesting is the discussion in Niezależny i oficjalny ruch ludowy w latach 1976–1989, drawn up by the Institute together with the Museum of History of the Polish People’s Movement, published in the work Represje wobec wsi i ruchu ludowego (1956–1989), vol. 2, Warszawa 2004. Very interesting are also works published outside of the Institute, e. g. by T. Sopel, Niezależny Ruch Chłopski „Solidarność’ w Polsce południowo-wschodniej w latach 1980–1989, Przemyśl 2000, and W. Hatka, Oblicze ziemi. Początki Solidarności Rolniczej. Dokumenty, kalendarium wydarzeń, Bydgoszcz 2007. They are more than just recollections.

[2] Archives of the Polish Institute of National Remembrance in Warsaw, no. 08/ 278. Acts of the object case Żywność [Food], vol. 13 p. 4, Kraków 10.08.1978. Information concerning the circles of the former popular right wing.

[3] Home archive of K. Bielańska, open letter of Roman Catholic priests to farmer priests – brothers across Poland, signed in October 1980 by the priests of the diocese of Kielce and Przemysl: Marian Gołąbek of Niegardów, Marek Ściana, Jerzy Łowicki and Stefan Walusiński of Bejsce, Franciszek Podolski of Lubla.

[4] Collection of the Foundation of the Documentation Centre for Independence, Archives of the Regional Chapter of Małopolska of ‘Solidarity’, file no. 105.

[5] Collection of the Foundation of the Documentation Centre for Independence, Archives of the Regional Chapter of ‘Solidarity’, file no. 105, no pagination, Warsaw, 14.12.1980, copy of the document sent to the Sejm of the People’s Republic of Poland by the foundation committee of the trade union ‘Rural Solidarity’ seated in Warsaw.

[6] B. Łuczywo, O co walczyliśmy i czego chcemy, ‘Rural Solidarity’, publication of the formation committee of ‘Rural Solidarity’ of Kraków, Autumn 1981.

[7] Archives of the Polish Institute of National Remembrance in Warsaw, no. 009/ 9112. Work file of secret operative ‘Lotos’, Maciej Marian Słomczyński, vol. 4, sheet 39, report by secret operative ‘Lotos’ of 17.12.1980.

[8] Archives of the Polish Institute of National Remembrance in Warsaw, no. 08/ 278. Acts of the object case Żywność [Food], vol. 13 p. 41-42, Kraków 27.01.1981. Action plan of operations on the object case ‘Rural Solidarity’.