The liquidation of private agriculture announced at the 15th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (b) in December 1927, was accelerated at the turn of 1929 and 1930 by means of mass terror. The program of "eliminating the kulaks as a class", i.e. the group of richer peasants constituting the rural elite, began to be implemented. This meant the doom of millions of the most enterprising and resourceful farmers – in order to intimidate others.

The goal of Stalin’s policy towards the countryside was to dispossess the peasants from their land and turn them into forced laborers - the "labor army", and soon into the real Red Army, whose soldiers were to die in the planned world revolutionary war. Its perspective was all the more iminent as a result of the outbreak of the Great Depression (1929) in free-market countries.

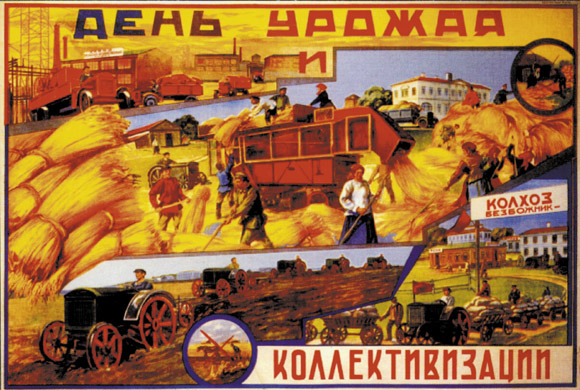

The Soviet state treated the peasants as a free labor force that would enable the planned industrialization and then would build heavy and armaments industries at a frantic pace.

The Bolshevik policy towards the countryside was characterized by all the features of "internal colonization". It resembled the exploitation of overseas colonial peoples and their wealth by European empires, which was widely condemned by Soviet propaganda. It was about controlling food, its production and distribution, and the unlimited amount of cheap labor that had to be directed from the countryside to communist industry.

The rural population rebelled against this criminal utopia. There were revolts and uprisings, especially in the Caucasus and Central Asia. In Belarus and Ukraine, peasants were hopeful that Piłsudski's troops would help. In Ukraine alone, according to OGPU reports (OGPU Russian ОГПУ, Объединённое государственное политическое управление, United State Political Board), in the first year of collectivization (1929) there were 1,3017 anti-Soviet incidents and up to April 1930 there had been 6,1 thousand anti-Soviet activities with the participation of over 1.7 million people.

Force was used to collect grain and herd people to collective farms. The party and administrative apparatus was used, special brigades of Komsomol being sent from the cities to terrorize the countryside. Crucial, however, was the violence of the OGPU. The fate of those arrested was determined - apart from the Soviet legal system - by specially appointed "three" composed of representatives of the party, the prosecutor's office and the NKVD - the latter having a decisive vote. The repressed "kulaks" were divided into three categories. The first one was intended for immediate execution, the second for deportation to distant parts of the country, usually to the north, and the third for regional deportation and forced labor.

By the end of 1930, functionaries of the repression apparatus had deported about 550,000 people, mainly women and children, to the north. 220 thousand were resettled within the region. Families whose fathers had been executed were forced to work in places of exile or in camps. The most tragic was the fate of the deported children, who suffered in the inhuman conditions of transport and exile, where their death rate often reached 40%.

By 1931, at least 1,050 million people had been repressed as part of the "kulak operation". In the spring of 1931, Stalin increased the pressure. In the second phase of the operation against the "kulaks", by September 1931, about 1.2 million people had been repressed, including 787,000 people deported.

The collectivization itself caused terrible famine, especially in Ukraine. It was done on purpose to break the peasants' resistance. Delivery standards were set and the grain was confiscated together with the grain for sowing. The climax was in the winter of 1932 to 1933 and in the spring of 1933, when half of the population was starving in Ukraine, there were cases of cannibalism. Attempts to escape to Poland were also made. Overall, collectivization had probably claimed about 6-7 million lives, of which about 4 million in Ukraine, about 1 million in the North Caucasus and southern Russia, and about 1 million in Kazakhstan.

Probably only between 1927 and 1933, as a result of collectivization and repression, a total of about 9 million people died, mainly in Ukraine. It is impossible to count the dead in camps, prisons and exiles, the victims of which by 1937 had probably amounted to between 1 and 1.5 million people.

These repressions made it possible to achieve Stalin’s main goal - they broke the resistance of rural societies, also on the non-Russian periphery, accelerated the liquidation of old social structures and extended the control of the totalitarian system to the countryside, which had eluded it so far.

These activities were closely related to the rapid expansion, from 1930, of concentration camps located in the north of Russia and in Siberia. The Gulag was filled with peasants and their families, and soon with other categories of prisoners. Soviet labor camps using slave labor in a system of forced labor, in which food rations depended on the fulfillment of particular tasks, became an integral part of the communist economy, especially the exploitation of the natural resources of the north.

About 1.3-1.5 million Poles remained behind the eastern border of the Second Polish Republic, established in 1921 by the Treaty of Riga ending the Soviet-Polish war. Among them were the descendants of the inhabitants of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth who had settled for centuries in the so-called further Borderlands, i.e. in the Soviet Ukrainian and Belarusian republics, as well as officials, intellectuals and workers leaving at the turn of the 20th century in search of work to larger centers - from Moscow and Leningrad (today: Saint Petersburg), Odessa, Kiev and Dnipro (today: Kamenskoye) to Azerbaijani Baku. Polish peasants received free land for settlers in Western Siberia and Kazakhstan, so they set up villages there.

After the Bolshevik coup in 1917, the Soviet authorities subjected various social and national groups to brutal repression in order to destroy their sense of identity and shape the "Soviet people" as part of a communist experiment.

The "socialist attack on the entire front" to break the resistance of the countryside ended in a fiasco in the lands inhabited by Poles.

The first phase of collectivization in the Marchlewszczyzna (i.e. the Polish National District), in the years 1929–1930, was a complete failure. By July 1931, only 7.2 percent of the total number of Poles had been registered as collective farmers, while the average in Ukraine was 61.5 percent. A year later, in July 1931, 61.5 per cent of the all Soviet farms had been collectivized, in Ukraine - 72 percent, but in the Marchlewszczyzna only slightly more than 15 percent.

This was clearly visible in comparison with other ethnic groups and drew attention to the enclaves of Polishness. The Marchlewszczyzna became proof of the failure of the collectivization plans in comparison the rest of the empire. By July 1932, 87 percent of German farms and over 95 percent of Jewish farms had been collectivized.

The collectivization in Ukraine had not been completed as planned in 1932. In order to break the resistance of Poles, like their Ukrainian neighbors, in mid-1933 famine was caused and the most relentless part of the population was deported. It was only the spectre of the death of starvation raging in Ukraine that forced Poles to join collective farms - by the end of 1933, almost 60 percent had been collectivized.

Hundreds of Polish families were deported in successive waves of the "kulak operation". Some left on their own accord, protecting themselves from starvation. In their place, refugees from central Ukraine, where there was even greater famine, arrived. Some people opposing the collective farms were displaced outside the Polish district. The liquidation of the so-called chutors, i.e. single, scattered farms, began and the population was concentrated in collective farms, under the control of the authorities, as a workforce. As a result of these actions, in 1933 alone the population of Marchlewszczyzna decreased by about 23%.

The resistance, however, did not stop, but moved to collective farms, where the authorities began to fight the so-called harmfulness, i.e. hidden forms of opposition. The collapse of collectivization in the Polish regions resulted in the growing suspicion against all Poles, including communist activists. Poles turned out to be more resistant to communism than Ukrainian or Belarusian peasants, hence the classification of a large part of them as "kulaks". For Stalin and the Soviet authorities, not only their "class" but also national consciousness were now becoming a threat and an obstacle that had to be physically eliminated.

The collectivization in Belarus was even more brutal. The Polish communists operating there tried to compete with Belarusian communists as to the pace of creating collective farms. Here, too, it turned out that a large part, as much as 23% of Poles, could be classified as "kulaks" - four times more than on Belarusian farms. This was due to the large number of descendants of the Polish farm nobility. In 1929, Poles constituted only 1 percent of kolkhozniks in Soviet Belarus.

Greater pressure from the authorities and the dispersion of the Polish population resulted in other forms of resistance here. It was passive or hidden. By 1931, 70 percent of Polish farms had been incorporated into collective farms, which was a better result than the average in Belarus. It was precisely these apparent successes in collectivization that allowed the establishment of Dzerzhinsk Region in Belarus in 1932 and its development in the early 1930s - at the same time when the liquidation of the Marchlewszczyzna and deportation of its inhabitants began in Ukraine.