The Battle of Warsaw was one of the most important moments of the Polish-Bolshevik war, one of the most decisive events in the history of Poland, Europe and the entire world. However, excluding Poland, this fact is almost completely unknown to the citizens of European countries. This phenomenon was noticed a decade after the battle had taken place by a British diplomat, Lord Edgar Vincent d’Abernon, a direct witness of the events. In his book of 1931 “The Eighteenth Decisive Battle of the World: Warsaw, 1920”, he claimed that in the contemporary history of civilisation there are, in fact, few events of greater importance than the Battle of Warsaw of 1920. There is also no other which has been more overlooked.

To better understand the origin and importance of the battle of Warsaw, one needs to become acquainted with a short summary of the Polish-Bolshevik war and, first and foremost, to get to know the goals of both fighting sides. We ought to start with stating the obvious, namely, that the Bolshevik regime, led by Vladimir Lenin, was, from the very beginning, focused on expansion. Prof. Richard Pipes, a prolific American historian, stated: “the Bolsheviks took power not to change Russia, but to use it as a trampoline for world revolution”.

The road to Europe opened up when Germany lost the First World War and signed the Armistice of 11 November 1918. The German troops then systematically retreated from the occupied lands of Ukraine, Belarus and other Baltic states. They were immediately followed by the Bolshevik Red Army, fulfilling Lenin’s orders to begin its “freeing” march west. This operation had a telling codename –“Vistula”. The most important goal for the Bolsheviks was to break through to Germany and Austria, where revolutionary sentiment prevailed. Hence, they needed to get rid of the “barrier”, meaning, as Joseph Stalin wrote, “the dwarf national states wound up between the two huge sources of revolution in the East and West”.

One such barrier was, first and foremost, Poland which had just regained independence following the defeat of Germany and the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. On 17 November 1918, at the Red Army briefing, its commander Leon Trotsky referred to the Sovietisation of Poland and Ukraine as “the links binding Soviet Russia with future Soviet Germany,” and the first stage in building “the Union of European Proletariat Republics”. A significant number of Poles lived on the territories of today’s Belarus and Lithuania, which had been, at that time, invaded by the Bolsheviks. Polish Self-defence units amounting to 10 thousand men were formed there. They were part of the Polish Army and their commander, Gen. Władysław Wejtko followed the orders of Chief Commander Józef Piłsudski. Between 3–5 January 1919, the Self-defence units attempted to defend Vilnius on their own. However, in the face of an overwhelming opponent, Poles had to retreat from the city. In view of the above, we can see that the Polish-Bolshevik war actually began on 3 January 1919, although it was not formally declared. The march West was accompanied by the establishment of Soviet puppet republics: Lithuanian, Latvian, Estonian, Ukrainian and Belarusian. The Western Rifle Division, consisting of Polish communists, marched among the ranks of the Red Army. On 8 January 1919, the Soviet newspaper “Izvestia” announced the establishment of the Revolutionary War Council of Poland, a cornerstone for a future communist government. Nonetheless, this date has not entered the Polish national consciousness, being overshadowed by other events of the year 1920.

Poles who fought for independence at the time imagined a reborn Polish state with borders similar to those the Republic of Poland had before the partition of 1772, including the Lithuanian, Belarusian and Ukrainian lands. (Absolutely no one had ever imagined back then the current borders of Poland, established after the Second World War, deprived of Vilnius and Lwów, the great Polish cities in the east.) Contemporary national movements of Lithuanians, Belarusians and Ukrainians developed in the former Polish lands in the east. The Chief Commander of the Polish Army and the Head of State, Józef Piłsudski was very well aware of that. Hence, he wanted to reconcile their desire to be free with the idea of a strong Republic of Poland by proposing the establishment of a federation.

Piłsudski’s main goal was the rebuilding of a strong Poland, capable of surviving between Germany and Russia. To achieve that, it seemed necessary to weaken Russia as much as possible by depriving it of not only Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania, but also Latvia, Estonia, Finland and Caucasian countries. This way, a bloc of “Intermarium” states was to be created. In opposition to Piłsudski’s concept of a federation, there was the nationalistic concept by another Polish leader – Roman Dmowski, rejecting the multinational Republic of Poland in favor of the ethnical “Poland for Poles”.

Under these circumstances, the clash between Poland and Bolshevik Russia was inevitable. Piłsudski had a serious problem on his hands, as the Polish state initially controlled a very small territory without the lands partitioned by the Germans and the lands east of the Bug river. The Polish Army was only just being formed and had to use most of its forces to fight against the Ukrainians for Lwów and Eastern Galicia. However, the Supreme Commander did not intend to just idly wait for the Bolsheviks to enter Warsaw. In February 1919, he launched a pre-emptive attack, entering the lands of today’s western Belarus left by the Germans. Despite having relatively small forces and being outnumbered by the enemy, he displayed great strategic skills. In April 1919, as a result of a successful offensive, Polish troops seized the region of Vilnius, and in the summer of 1919, most of the Belarusian lands up to the line of the rivers Daugava and Berezina. The “Polish barrier” prevented the Bolsheviks from coming to the aid of the communist republics in Hungary and Bavaria.

Piłsudski then made an address to the citizens of the former Grand Dutchy of Lithuania, promising them independence and self-proclamation. In reality, he intended to bind the reborn Grand Dutchy of Lithuania with Poland in a federation, divided into three parts: the Lithuanian one (with the capital in Kaunas), the Polish one (Vilnius lands) and the Belarusian one (with the capital in Minsk). Unfortunately, the Belarusians, with their weak national identity, were indifferent to this offer, while the Lithuanians, already being in possession of their own state, proved to be hostile to the idea.

These Polish successes in Belarus were only possible due to the fact that the Bolsheviks had to fight on several fronts, and their main opponent at the time was the Russian White Army, led by Gen. Anton Denikin. In the face of Denikin’s offensive, led from the south to Moscow, in the second half of 1919, the Polish-Bolshevik front became, in fact, a secondary front. Piłsudski then made a truce with the Bolsheviks, since he was not able to come to an understanding with the Russian White movement. It is worth mentioning that General Denikin accepted independent Poland only west of the Bug river. He did not acknowledge Ukraine’s independence and was not interested in any compromise. He was supported by the Entente countries: France and Great Britain. In this situation, Denikin’s victory would mean that Poland would be reduced to being a small country, between great Russia and Germany.

Contrary to Bolshevik claims, and today’s Russian propaganda, Józef Piłsudski was never filled with hatred towards Russia and the Russian people. He simply understood that Russia, be it white or red, would always be an imperialistic state. The war with the Bolsheviks should not be regarded as a Polish-Russian war. Piłsudski stressed this in one of his orders: “We are not fighting against the Russian nation, but against the Bolshevik system”. Following Denikin’s defeat, he placed his bets on the democratic “Third Russia”, initiating in January 1920 cooperation with Boris Savinkov – the leader of the socialist-revolutionary party, who had established the Russian Political Committee in Warsaw. Under this agreement, small Russian units later joined Poles in the fight against the Bolsheviks.

Piłsudski’s ambitious plans regarding Russia can be divided into three stages:

-

Breaking of the “First Russia” (white) making use of the Bolsheviks,

-

Breaking of the “Second Russia” (red) by the Polish Army;

-

Creation of the “Third Russia” ( democratic).

A close alliance with the independent Ukrainian People’s Republic was also an important element of this plan. The Head of State recognized the key importance of Ukraine for the future shape of this part of Europe. The road to this alliance, however, was long and complex due to the ongoing Polish-Ukrainian conflict in Eastern Galicia. Only after it had ended, was it possible to initiate talks. Finally, in 1919 the forces of the Ukrainian People’s Republic gave in to the overwhelming Bolshevik army and the Supreme Otaman Symon Petliura took refuge in Poland. Lasting several months, the secret Polish-Ukrainian talks came to a hault on 21 April 1920 with the signing of a political agreement in Warsaw between Poland and the Ukrainian People’s Republic. Symon Petliura, guided by political realism, waived his country’s claims to the lands of Eastern Galicia and western Volhynia. Poland, in turn, acknowledged Ukraine’s independence and promised its assistance in the fight against the Bolsheviks.

The so-called Kiev Offensive, undertaken by the Polish and Ukrainian forces in the spring of 1920, has always been presented by Russian propaganda as the Polish aggression against Soviet Ukraine and “the third march of the Entente”. In reality, it was a pre-emptive attack, similar to the Vilnius offensive of April 1919. The proposals of signing a truce, put forward by the Bolsheviks since December 1919, were nothing more than a smoke-screen. They were, in reality, calculated for a propaganda effect – fooling the international public opinion and weakening the combat readiness of the Polish Army. Meanwhile, preparations for the invasion of Poland were ongoing. A plan of the offensive was ready and the Red Army mustered its troops near Smoleńsk.

Thanks to the work of the Polish intelligence, Piłsudski was well aware that the Bolsheviks intended to strike at the northern front line – in Belarus. Nonetheless, he decided to first launch a pre-emptive attack in the south – in Ukraine. Then, the allied Ukrainian army was to defend the taken positions, and the Polish forces would mostly be transferred to Belarus to deal with the northern Bolshevik troops. In a conversation with his assistant, Piłsudski said: “…the Bolsheviks need to be beaten and it needs to happen soon, until they grow in strength. We need to force them to engage in a decisive battle […] Kiev, Ukraine, this is their weak spot. It is so for two reasons: first, Moscow will be in danger of starvation without Ukraine; second, if we threaten them with the establishment of independent Ukraine, they will not be able to risk it and will be forced to meet us in battle”.

The offensive, started on 25 April 1920 by the allied Polish and Ukrainian forces, showed a lot of promise. Many prisoners were captured and large amounts of military equipment were acquired. However, the Bolsheviks were not that easily fooled and retreated behind the Dnieper river, avoiding a decisive battle. On 7 May, the troops under Gen. Rydz-Śmigły’s command captured the abandoned Kiev. On 14 May 1920, the Bolsheviks immediately began their offensive in Belarus. It was stopped at the expense of transferring Polish reserves there. Meanwhile, the 1st Bolshevik Cavalry Army of Semyon Budyonny was sent to fight in Ukraine. On 5 June 1920, it broke through the lines south of Kiev and ended up on the rear of the Polish army. Under these circumstances, Gen. Rydz-Śmigły ordered a retreat from Kiev. The “Kiev Offensive” ended in defeat.

The main reason for the defeat, apart from the mistakes made by the Polish command, was the weakness of the Ukrainian People’s Republic’s army. This army had not been expanded due to many factors: a lack of trust towards Poles on the part of the Ukrainian population, a limited number of volunteers, improper behaviour of some of the Polish soldiers in the freed Ukrainian territories, and first and foremost, the lack of time to conduct wide mobilisation. The army only amounted to 20 thousand soldiers. Nonetheless, until the end of the war, it fought bravely against the Bolsheviks alongside the Polish Army. Hence, some historians call the 1920 war the Polish-Ukrainian-Bolshevik war.

Several attempts made by Poles to stop the large cavalry unit, which was the 1st Cavalry Army, were not successful. The Bolshevik Southwestern Front was forcing the Polish troops out of Ukraine. On 4 July 1920, the Western Front led by Mikhail Tukhachevski commenced a decisive attack in Belarus. Two days earlier, he gave his famous order: “Soldiers of the workers’ revolution – turn your eyes to the west. The fate of world revolution is being decided in the west. Over the corpse of White Poland lies the road to worldwide conflagration. On our bayonets we will carry happiness and peace to working humanity. To the west, to decisive battles, to great victories! Form your ranks, the hour of the offensive to Vilnius, Minsk, and Warsaw has struck. Forward!". The Polish Army was incapable of stopping the overwhelming enemy and was forced to retreat. On 14 July, the Bolsheviks took Vilnius. Polish troops were still retreating to the west, although they did not allow the Bolsheviks to surround them and break them up, without losing their combat value. In the face of the defeats on the front line, the Council of National Defense, consisting of the Speaker of the Seym, the Prime Minister and representatives of the government, the army and parliament, was established on 1 July. The Council was fully authorized to make decisions regarding war and peace.

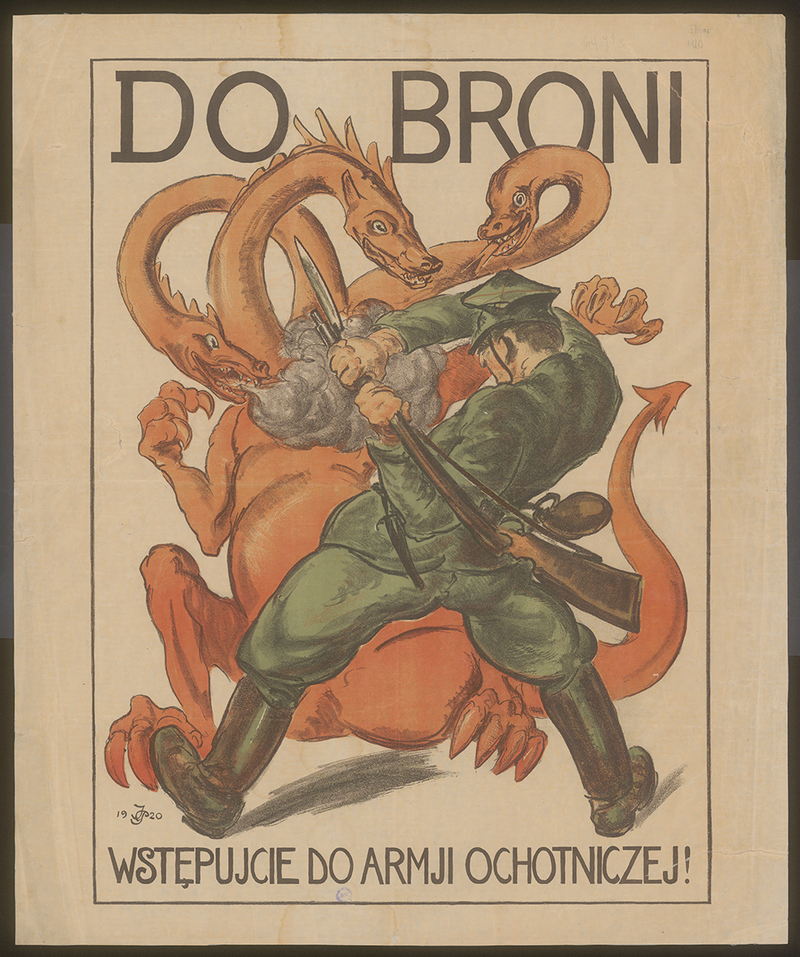

On 3 July, the Council made a dramatic address to the nation: “As a unified, indomitable wall we must mount resistance. The wave of Bolshevism has to break against the entire nation. […] Therefore, we ask everyone capable of carrying arms to volunteer and enlist for the army, showing that Poland is ready to shed blood and sacrifice lives for the Homeland”. The Catholic Church played an important role in mobilising the society. Polish bishops, in a letter to the faithful, stated that Bolshevism was the enemy of Christianity and culture in general, leaving behind nothing but death and destruction: “Truly, the spirit of the anti-Christ is its inspiration, its motivation for plunder and conquests ”. More than 100 thousand men enlisted, including 30 thousand residents of Warsaw.

The army needed weapons and equipment, which forced the government to seek help abroad. British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, instead of aiding Poland, offered to mediate in peace talks with the Bolsheviks, who demanded to set the border at the so-called Curzon Line (similar to the current eastern border of Poland), limit the Polish army to 50 thousand soldiers and practically hand over power to Polish communists. These conditions were absolutely unacceptable for the authorities in Warsaw. France reacted differently, offering deliveries of large amounts of weapons and ammunition. One of the few people to understand the gravity of the situation was Pope Benedict XV, who wrote in a letter of 5 August: “Currently, not only Poland’s national existence is in danger, but also all of Europe is threatened with the atrocities of a new war”.

As part of a huge propaganda campaign under the motto “Hands off Soviet Russia” Moscow mobilised communist parties and leftist trade unions across all of Europe to act against Poland. Many western journalists were on the payroll of Bolshevik propaganda. Railway workers in Germany and Czechoslovakia blocked the aforementioned deliveries of military equipment to Poland. Governments of both states silently supported the Bolsheviks. The only safe way for these transports led through Romania.

On 23 July 1920, the Provisional Polish Revolutionary Committee (Polrewkom) was created in Smoleńsk. It was headed by Julian Marchlewski and Felix Dzerzhinsky. It later established its seat in Białystok, taken by the Bolsheviks. Revolutionary committees and red militias were established in the field, introducing new Soviet order. However, Polish workers and peasants did not yield to communist agitation. They gathered around the Government of National Defense, created on 24 July. Wincenty Witos, the leader of the Polish People’s Party , became its Prime Minister, while Ignacy Daszyński, the leader of the Polish Socialist Party, became its deputy Prime Minister. Witos played an enormous role in mobilising the peasants, as the largest social class, to fight in defence of the country.

The Red Army, due to political reasons, advanced in two different directions, which later became its demise. After all, Poland was only the starting point for attacking western and southern Europe. Mikhail Tukhachevski’s Western Front pushed in the western direction to Warsaw, with the intention of breaking through to Germany. In the meantime, the Southwestern Front commanded by Alexander Yegorov turned towards the southwest, to cross the Carpathian mountains after taking Lwów and Eastern Galicia. Yegorov’s deputy, in the role of a political commissar of the front, was Joseph Stalin. On 23 July 1920, Lenin sent a telegram to Stalin: “Zinoviev, Bukharin and I believe that we need to immediately begin a revolution in Italy. I personally think that in order to do that, we need to Sovietise Hungary, and perhaps Czechoslovakia and Romania as well”.

If Lwów had been captured by the Bolsheviks, Hungary would have indeed been in real danger, since the President of Czechoslovakia Tomáš Masaryk was ready to voluntarily give away Carpathian Ruthenia to the Bolshevics. Hungarian politicians were well aware of that fact. Hence, Hungary, having been humiliated by the partition treaty in Trianon, in this tragic moment for their country, decided to support Poland. The ammunition factory on Csepel island was the only available source of ammunition deliveries for Austrian and German weapons, which constituted the equipment of half of the Polish Army.

Prime Minister Pál Teleki ordered all the stocks of ammunition and all production output to be sent to Poland. In the face of the blockade introduced by Czechoslovakia, the transport reached Poland indirectly, through Romania. Several days before the final battle, 35 million rifle cartridges and 30 thousand Mauser rifles reached Warsaw that way. On 22 July 1920, Teleki appealed to all of Europe to support the fighting Poland. He also offered to send military reinforcements. On 1 August, the Hungarian army consisting of almost 100 thousand soldiers was put into combat readiness. However, the transport of the troops to Poland did not take place, as it required the agreement of the Entente and Czechoslovakia or Romania. An idea of creating a Hungarian Legion in Poland was also put forward. In the end, only a handful of Hungarian volunteers managed to take part in the fight against the Bolsheviks, south of Lwów.

Tukhachevski intended to strike Warsaw from two sides – his main forces advanced on the capital of Poland from the east, while one of the Bolshevik armies was to flank Warsaw from the north, cross the Vistula river near Płock, and attack the city from the west. Budyonny’s 1st Cavalry Army, at the time attacking Lwów, was to serve as additional support in the fight for the Polish capital. Tukhachevski demanded for it to be transferred to Warsaw. However, the commanders of the South-western Front, Yegorov and Stalin, opposed that idea, as they wanted to seize Lwów at all costs and quickly march to Hungary.

The fierce fighting in Lwów ended with the Bolsheviks’ defeat, since they were unable to capture the city. This region was of significant strategic importance because the railway connection to Romania running through Lwów, enabled the delivery of weapons and ammunition from Hungary and France. The railway line was also covered by the allied Ukrainian army, led by Gen. Mykhailo Omelianovych-Pavlenko, which defended the almost 150 kilometre-long stretch of the Dniester river.

The fact that Tukhachevski’s troops were attacking Warsaw, while Yegorov’s forces were attacking Lwów resulted in a large gap between their units. Within a 140 kilometre distance between the Vistula and Bug rivers, in the region north of Lublin, only weak Bolshevik units were present. Chief Commander Józef Piłsudski decided to take advantage of that and attack from the south Tukhachevski’s rear forces advancing on Warsaw.

For the Polish plan to succeed, it was necessary to have control over the fortification line near Warsaw, east of the Vistula river, until the troops were transferred and Piłsudski’s offensive was launched. Fierce fighting took place in Radzymin and its surroundings (25 kilometres from the center of the Polish capital). For three days, the city’s fate was undetermined, but in the end, the enemy’s attack was countered. One of the fights which became legendary was the one near Ossowo on 14 August, where a chaplain of the volunteers from Warsaw, priest Ignacy Skorupka died holding a cross in his hand. Furious fighting also took place north of Warsaw and on the Vistula river in Płock, in defence of the crossing.

Lenin was urging his comrades to increase the pace of their military activities. At the session of the Bolshevik Political Bureau on 12 August, he firmly stated: “From the political standpoint, it is of utmost importance to finish Poland off”. It were Poles, however, who destroyed the Red Army. The offensive between the Vistula and Bug rivers, carried out from 16 August 1920, forced Tukhachevski’s army to retreat in panic. Only on the first day, Poles advanced 45 kilometres up north. After 10 days, the enemy was crushed. As a result of the Battle of Warsaw, the Red Army lost 25 thousand men who were killed in action, 66 thousand being taken prisoner. Almost 50 thousand Bolsheviks, whose escape route had been cut off, took refuge in the German Eastern Prussia.

The Bolsheviks made attempts to regain initiative, but in September 1920 they were defeated once again near the Niemen river. In the beginning of October, the Polish Army, supported by the Ukrainian allies and small troops of Belarusians and Russians, approached the line which they had reached a year prior (before the Kiev Offensive). They captured Minsk and were only 140 km away from Kiev. However, the Polish society and politicians had enough of war and wanted peace. Lenin, for the time being, abandoned his plans for conquering Europe, since he had to deal with the White Russians’ and peasants’ revolutions across the entire country. Hence, on 18 October 1920, a truce went into effect on the Polish-Bolshevik front.

The truce meant the end of the Polish-Ukrainian alliance. The Ukrainian troops, as well as Savinkov’s Belarusians and Russians tried to continue their war against the Bolsheviks on their own, but within a month they were defeated by the overwhelming forces of the enemy. Based on the Polish-Soviet peace treaty in Riga, the lands of today’s Belarus and Ukraine were partitioned. Most of them were incorporated into the Soviet Union, and some into Poland. Poland had defended its independence, but Piłsudski had to abandon his concept of a federation.

British diplomat Lord Edgar d’Abernon, who in the summer of 1920 stayed in Poland, called the Battle of Warsaw the eighteenth decisive battle of the world (in chronological order). It was, in his opinion, an event of global importance, the clash of two different civilisations. In his book, d’Abernon stressed the fact that Poles had been the ones who had first saved the western civilisation when king Jan III Sobieski defeated the Muslim Turks on the outskirts of Vienna in 1683. In turn, in 1920, Poland saved Europe from “an even more revolutionary threat, meaning the fanatic tyranny of the Soviets”.

Following the defeat in the Battle of Warsaw, Lenin said: “We will conquer Poland anyway, when it is time. Against Poland, we can unite the entire Russian nation and even make an alliance with the Germans. […] They want revenge and we want a revolution. For the moment, our interests are aligned”. Nineteen years later, the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact was signed, and Stalin began his conquest of Europe. On 17 September 1939, he invaded Poland while it was defending itself against the Germans occupying half the country. In the spring of 1940, almost 22 thousand Polish citizens (Polish officers and members of the country’s elites) were brutally murdered in Katyń, Mednoye, Kharkiv, Bykownia and Kuropaty. The Katyń Massacre is often perceived as Stalin’s revenge for the lost Battle of Warsaw.

In order to justify the Katyń Massacre, in its historical policy Russia created the “anti-Katyń”. Poland has been accused by Moscow of murdering Bolshevik prisoners captured during the 1920 war. In reality, between 16 to 18 thousand POWs died in Polish captivity. The main reason behind their deaths were the typhus and dysentery epidemics, which also killed many Polish civilians. At the same time, the Russians are omitting the fact, that nearly 15 thousand Polish prisoners never returned from Soviet captivity, that they were kept under horrible conditions, often dying of diseases, starvation and exhaustion from forced labor.

Between 1944–1945, Stalin conquered half of Europe, exporting the revolution on the bayonet points of the Red Army and stopping only at the “iron curtain”. However, thanks to the Battle of Warsaw, Poland and other countries of Central-Eastern Europe gained enough time to build their statehood and strengthen their national identities. After the Second World War, they were forced to succumb to Moscow, but they could not be incorporated into the Soviet Union entirely. Additionally, the countries of Western Europe were saved from communism. The Battle of Warsaw was, therefore, the first defeat of the Evil Empire. Thanks to the Polish victory, the fate of the world turned out differently than it had been desired by Lenin. Shortly after the defeat near Warsaw, the leader of the Bolsheviks admitted: “The Polish war was the most important turning point, not only for the politics of Soviet Russia, but for global politics as well. […] We could have had everything there, in Europe. But Piłsudski and his Poles caused a gigantic, unprecedented defeat of the global revolution cause”.

Mirosław Szumiło, D.Sc.