Since the beginning of the war, millions of people had hoped that Germany would be defeated. In the first years of the war, however, it were the Allies who suffered defeat after defeat. Only since 1943 did the dream of Europe free of German occupation begin to take shape. The Allies controlled all of Africa and landed in Italy. The Soviets pushed west from the Volga river. Both sides of the front realised that a landing in France was next.

The Germans built the West Wall which was aimed at stopping the Allies, while thousands of members of the French resistance gathered intel on these preparations. They wrote down the locations and characteristics of bunkers, how they were armed and where the command centres were.

On the West Wall

The Germans built the West Wall which was aimed at stopping the Allies, while thousands of members of the French resistance gathered intel on these preparations. They wrote down the locations and characteristics of bunkers, how they were armed and where the command centres were. Moreover, they even measured the size of rocks on the beaches, which was only seemingly pointless; the American and British armoured personnel needed to be certain that the tank tracks wouldn’t get stuck. The Interalliee intelligence network, led by Polish air force captain, Roman Czerniawski, actively took part in these preparations.

The date of the invasion of the Old Continent was postponed multiple times. At first, it was due to political reasons and then purely tactical ones. The night and subsequent day of the invasion had to have perfect conditions. It needed to be high tide for the landing craft to sail over underwater traps. The moon had to be full for the navigators of the transport planes, with thousands of paratroopers on board, to find the drop points. Last, but not least, there had to be perfect weather conditions. Too strong winds would cause the waves to be unbearable for the landing craft and swimming tanks, while a fog and clouds would make the air force and artillery warships blind.

The beginning of June, 1944, was the next best date. In the first days of this month, however, a heavy storm came over the English Channel. It was simply impossible to send the landing troops out into the sea or dropping the paratroopers. The Germans decided that the invasion was out of the question. Most of the soldiers left the bunkers and stayed in the warm quarters. Commanders of many units left for staff exercises in Paris. Even the main commander in France, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, went to Germany. In the meantime, British meteorologists forecast that on the night of June 5 and in the morning of June 6, 1944, the weather would get better for more than a dozen hours. The invasion machine was set in motion.

The invasion

A thousand and a half transporters went out into the sea (including ten under the Polish flag), carrying more than four thousand landing craft filled to the brim with soldiers and equipment. Additionally, there were more than 1,200 landing craft support ships. These included Polish destroyers Błyskawica (Lightning) and Piorun (Thunderbolt) which helped block the German ships from entering the two sides of the canal.

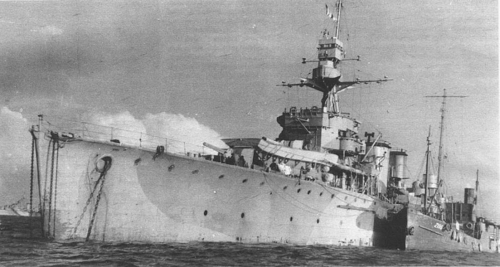

The escorting destroyers Krakowiak (Cracow Man) and Ślązak (Silesian Man), as well as the Dragon battle cruiser, were assigned to naval gunfire support of the landing forces. Since 7 a.m., on June 6, they efficiently dealt with the coastal artillery batteries and the groups of German tanks preparing for the counterattack. Unfortunately, the Dragon cruiser ran out of war luck on the night of July 7 and July 8. It was torpedoed by a pilot of a live German Neger torpedo. 37 sailors lost their lives and the cruiser suffered so much damage that it was decided that it would be sank on purpose. It was towed to the Mulberry artificial port where it strengthened the breakwater. Earlier, on June 8, the same breakwater was strengthened with the sinking of the Modlinsteamship (earlier it served as the Wilia transporter).

Ten thousand allied planes, bomber and fighters, flew above the invading forces and later over the beaches of Normandy. The aircraft were painted in the characteristic black and white stripes (called zebras by the invading troops) which helped to identify them. There were three Polish bomber squadrons in the air forces, responsible for directly supporting the landing troops, and eight fighter squadrons which helped control the skies over the Canal, the battlefield and entire northern France.

In the second phase of the invasion, the 1st Polish Armoured Division joined the operation near Caen.